Issue No. 4 | August 2, 2017

Essays

Debating and dissecting Westbrook’s style has become a tradition and an ongoing concern for a wide swath of sportswriters, broadcasters, journalists, and fans. In general, however, whereas the sports media has often seen Westbrook’s style choices as a sign of inauthenticity, the fashion industry has almost unanimously embraced these same choices as sign of authenticity.

This essay looks at advertisements that appeared in three turn-of-the-century fashion magazines — exploring how the fashion industry in some ways participated in the perpetuation of normative gender roles, but in others created a more subversive counter-narrative.

With the word “cool” completely drained of meaning — used today in an excessive, inflationary way — it seems extraordinary that coolness can still be linked with specific garments and characteristics. Indeed, no other garment has been so continually associated for so long with coolness as the black leather jacket. At once, it is part of the fashion industry’s mass-market repertoire yet, barely having changed form over the last century, it stands as a classic symbol of affectlessness, individuality, and non-conformism.

Visual Essays

“You’ll be happy to hear that you’re not dead,” said Simon as he pressed a cool towel to my forehead. I was lying on the concrete floor of my studio. I felt weak — my body had just failed me. I had fainted in the middle of making a full-scale cast impression of my body that would become my own, highly personal, dress form.

From years of personal observation, I discovered that art made by children is often valued by families and preserved for the future. Applying this observation to the design practice, I figured that using such artworks for clothing design could add value to garments.

During my mother's childhood, it was common to have a small, special wardrobe of Sunday clothes (Pyhävaatteita in Finnish). Gradually, after wearing them out, Sunday clothes became ordinary, everyday clothes. This process through which garments go from being sacred to mundane beautifully represents the long lifecycle of garments. Nowadays we don’t wear Sunday clothes anymore; however, we should still try to see that same practical dignity in all of our garments.

Notes from the Field

This issue brings us two reports from scholars working within the academic system, both of whom have found ways to use that structure to think more personally about fashion, dress, history and psychology. In reading through them both, we as editors are left thinking about the deep connections between our emotions, our dress, and our work.

I'm not going to be able to share any groundbreaking pedagogy in this article. I will, however, give some perspective into what happens when we — speaking on behalf of those who struggle to make an impact in academia — remove ourselves from the politics of our competitive field in order to focus on doing what we love.

My motivation in wanting to understand how we experience wearing the positive feeling of being happy is based on my personal relationship with my wardrobe and the way I feel about dressing. Fashion creates meaning in my life, dress connects me to others, and clothes allow me to engage with my creativity. I wanted to learn if that was also true for others.

From the Archives

A hand-scrawled note reads: “Now that Fashion’s Gone to Hell And Dress has become neuter." The phrase floats alone in the center of a small note page—the type of thing one might expect to find today, coffee-stained and abandoned amid a mess of stir sticks and sugar crystals on a vacant table at Starbucks, except this particular note dates to a very pre-Frappuccino® era, written sometime around 1969 by the resident of apartment #429 of the famed bastion of New York bohemian culture, the Hotel Chelsea. It was written by the one-and-only Elizabeth Hawes.

What We're Wearing

A large file of scanned photographs arrived in my inbox one afternoon, put together by a younger cousin, carefully preserved by my uncle, a historian. These were the first images I had ever seen of my grandmother.

My style is a testament to the beauty and effortless cool that women of color, and in particular, BLACK women, possess. It was in this spirit that I chose to reflect the rich legacies of the black women who came before me through my visual project, #WhoButABlackWomyn.

Profiles

Otherworldly, futuristic, ancestrally familiar, avant-garde. It’s hard to find words that fully grasp the experience that is JEEPNEYS, a name once used for multidisciplinary artist Anna Luisa Petrisko and more recently to include research-based collaborative works.

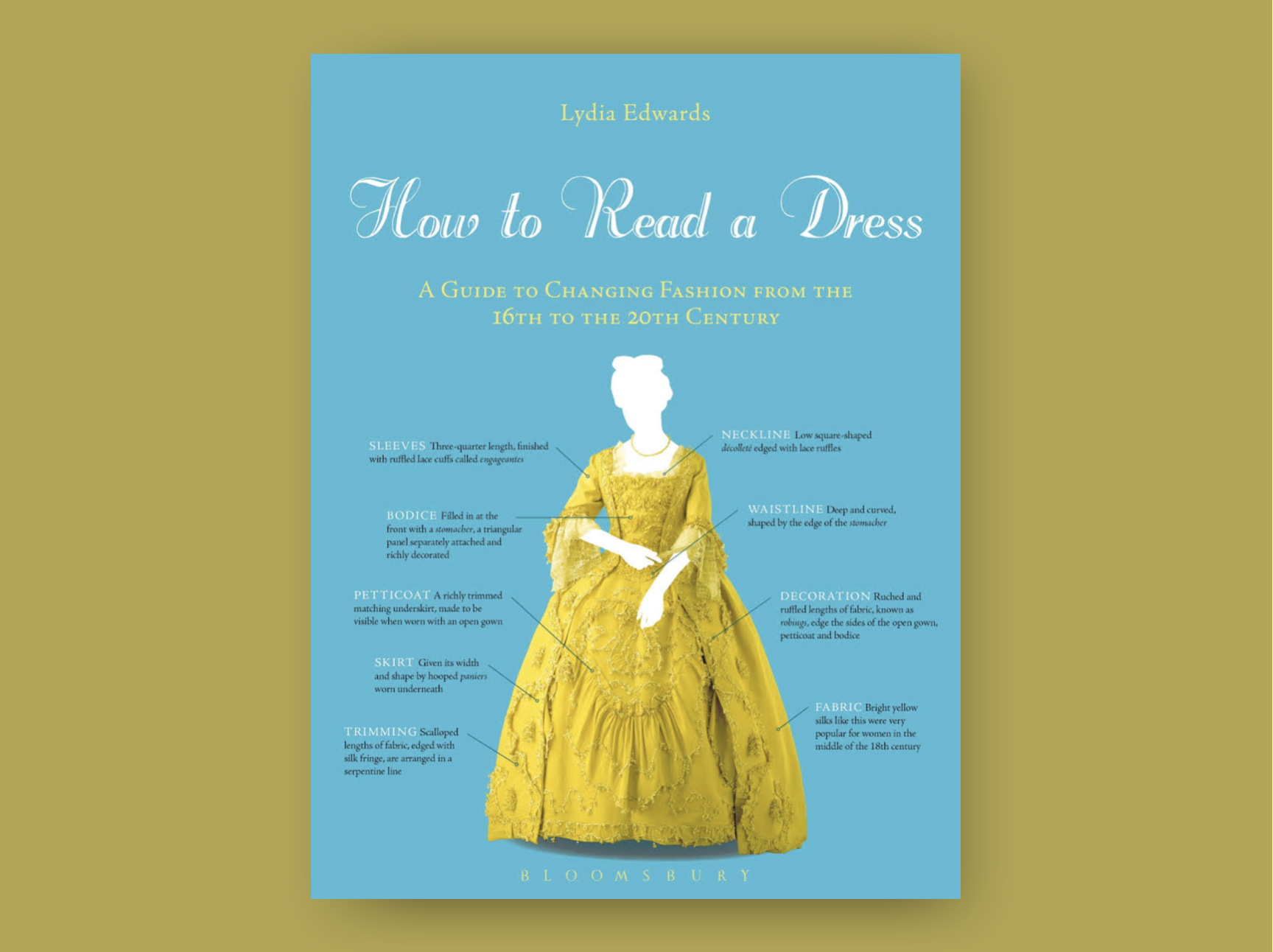

As you walk around the space, you’re surrounded by a constellation of work, from photographed portraits to what Fabiola is most well-known for: elaborate paper dresses. Easily mistaken for fabric garments, it’s the uncanniness of Fabiola’s paper dresses that attests to her appreciation for fashion history.

Histories

It was an itsy bitsy, teenie weenie, yellow polka dot bikini…. This catchy tune is as much a part of the summertime for many of us as ice cream. Despite years of singing this song on my way to the pool, it was only once I began researching the bikini’s origins that I found the multiple links between this popular swimsuit style and mid-20th century military developments.

In the late nineteenth century, there was steady coverage in The New York Times about the act of dress smuggling. This act, often referred to as "fashionable smuggling,” involved the practice of smuggling European-made gowns and dress goods into the U.S. Whether a quick report or an in-depth exposé, the focus of each story is smuggling's relationship with the women involved, and of the women who were reported to have smuggled.

Emerging Scholar

It has come to my attention that communication technology has a profound influence on the lives of people, especially the younger generations. My hypothesis is that the increased use and reliance on gadgets such as smartphones creates a decrease in face-to-face social interaction and empathy, creating a world of virtual interactions and loneliness instead.

Reviews

Edited by Agnès Rocamora and Anneke Smelik

Victoria & Albert Museum (May 27th, 2017 – Feb 18, 2018) and Musée Bourdelle (March 8th – July 16th, 2017)

Fashion Museum Bath (February 4, 2017 - January 1, 2018)

The Brooklyn Museum (March 3 - July 23, 2017)

Fashion Space Gallery (May 12, 2017 - August 4, 2017)

FIDM Museum & Galleries (June 6 - July 8, 2017)