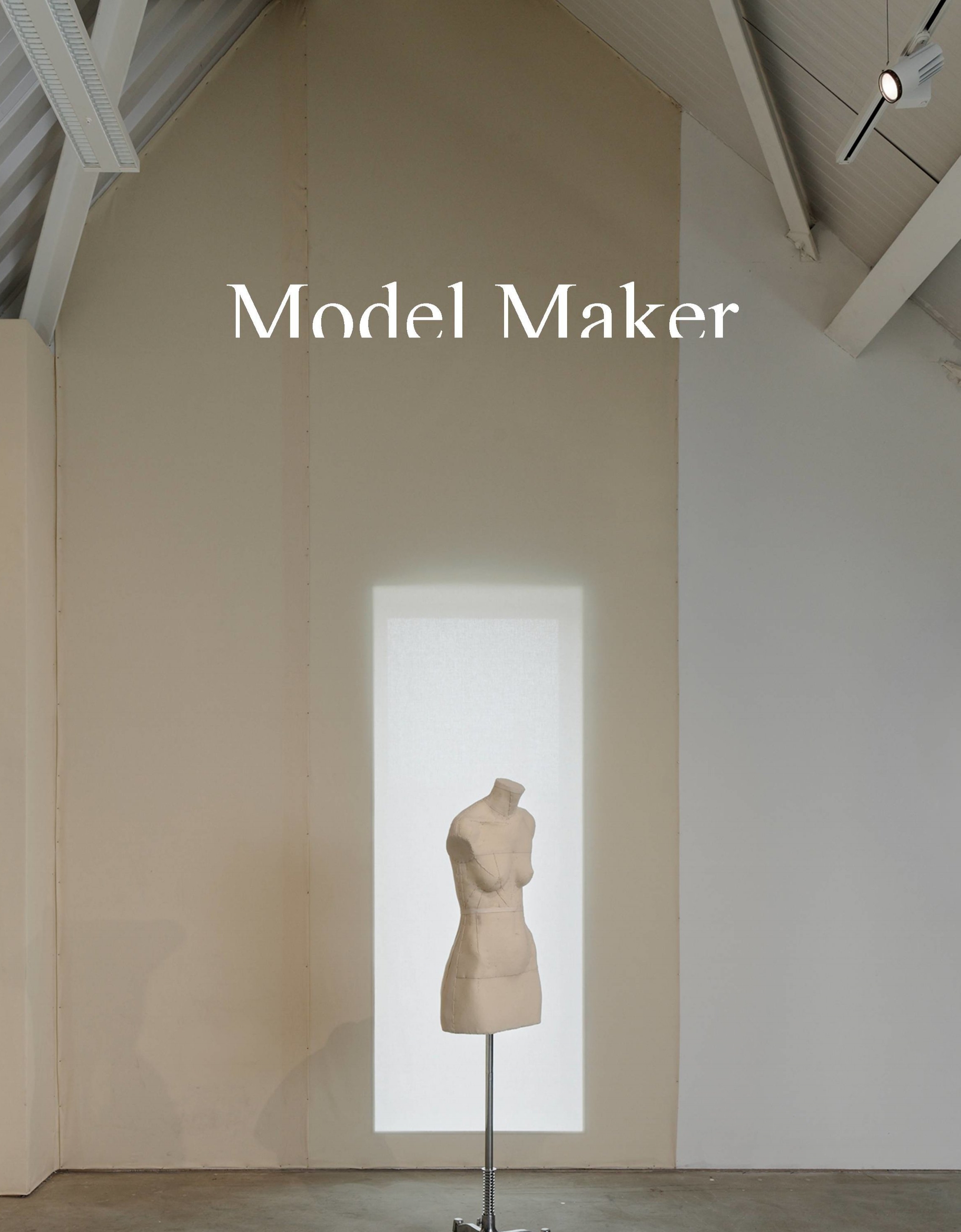

Model Maker

“You’ll be happy to hear that you’re not dead,” said Simon as he pressed a cool towel to my forehead. I was lying on the concrete floor of my studio, my head cradled in his hand, staring up at his upside-down face. I felt weak — my body had just failed me. I had fainted in the middle of making a full-scale cast impression of my body that would become my own, highly personal, dress form.

I had spent the previous three hours with Simon and another man as they covered me in body-grade silicone and plaster to create a negative cast of my figure. Standing on a plastic tarp, I had greased my nakedness in Nivea cream — a natural release agent that would form a layer between my flesh and the silicone. While I greased, Simon prepared the silicone.

When the silicone was ready, I scooped up a glob with my hand and covered my own ‘bits’ as Simon referred to them (my nipples, my crotch). The material went on like cake frosting — sticky and gloppy with a purple color. Then, I held my posture stood perfectly still as the guys covered the rest of my body. They used spatulas, “icing” over my torso and the crack of my butt, covering me in what looked like a purple cocktail dress with a mock collar and cap sleeves.

By the time they had covered my body, the silicone had started to set. Now it was time for the plaster. As if bandaging a broken arm, they covered the silicone with cool strips of wet plaster cloths. But plaster sets with a chemical reaction that causes it to warm as it hardens. When the plaster warmed, all of my internal organs went from cold to hot in just a few minutes.

A few minutes later, I lay collapsed on the floor.

A sculptor smothered by her own Frankenstein. A disappointed Prometheus who couldn't even breathe life into her own form, let alone into the form of another.

In the weeks leading up to this moment, my sculptural practice had led me to the desire to make my own tool: a dress form. I am a sculptor who uses a range of processes: glassblowing, printing, casting, welding, and sewing among others. In each of these practices, my body is my most valuable tool — it is the way I make, the way I see, the way I interact with the world. My body can do anything I ask it to do — I am proud of my body.

But a dress form is no ordinary tool: to turn the malleable female form into a rigid object would transform it into a sculpture — and quite a classical sculpture at that. In effect, I would be making a very classical sculptural object — a sculpture of the naked female form.

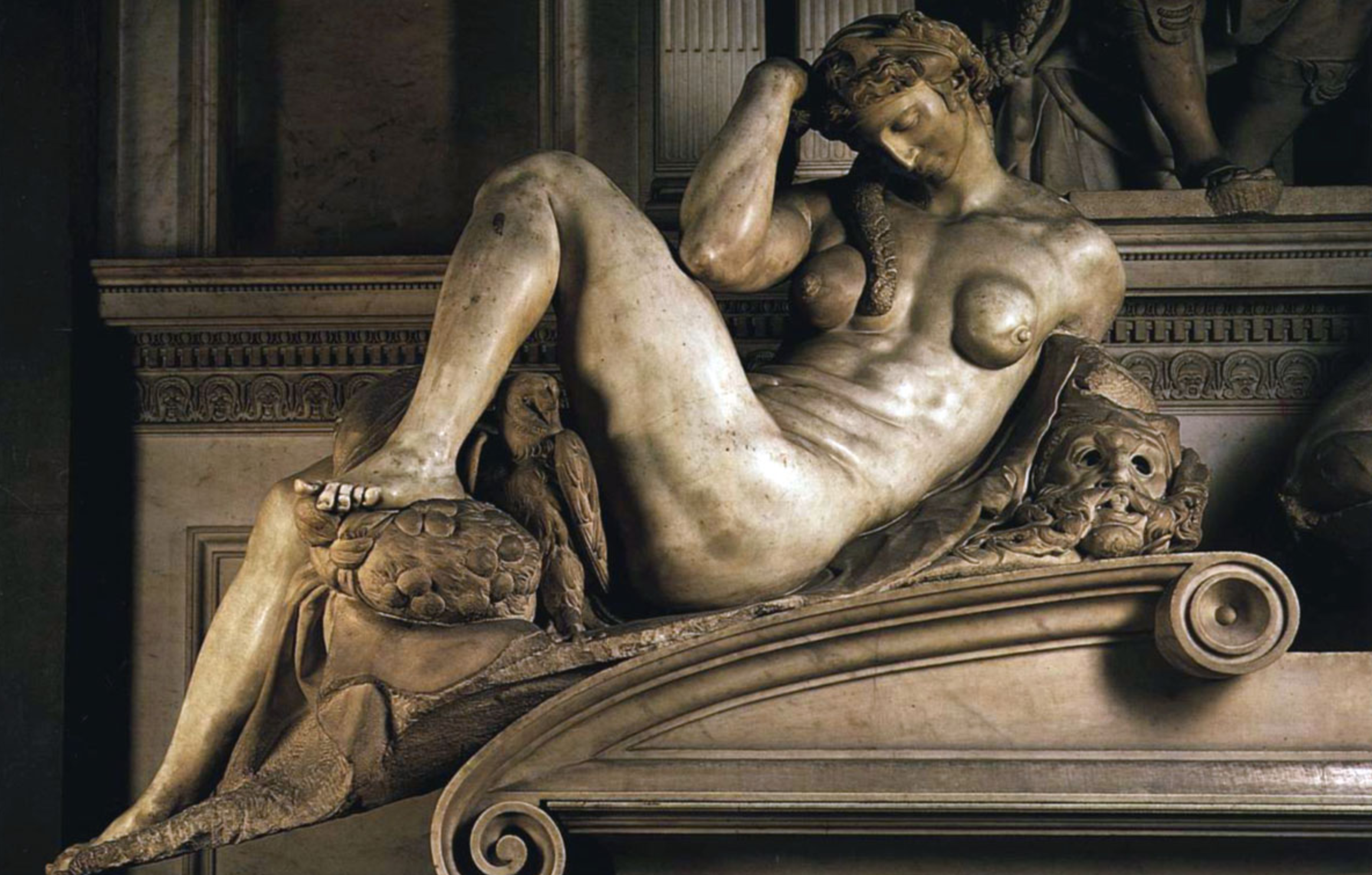

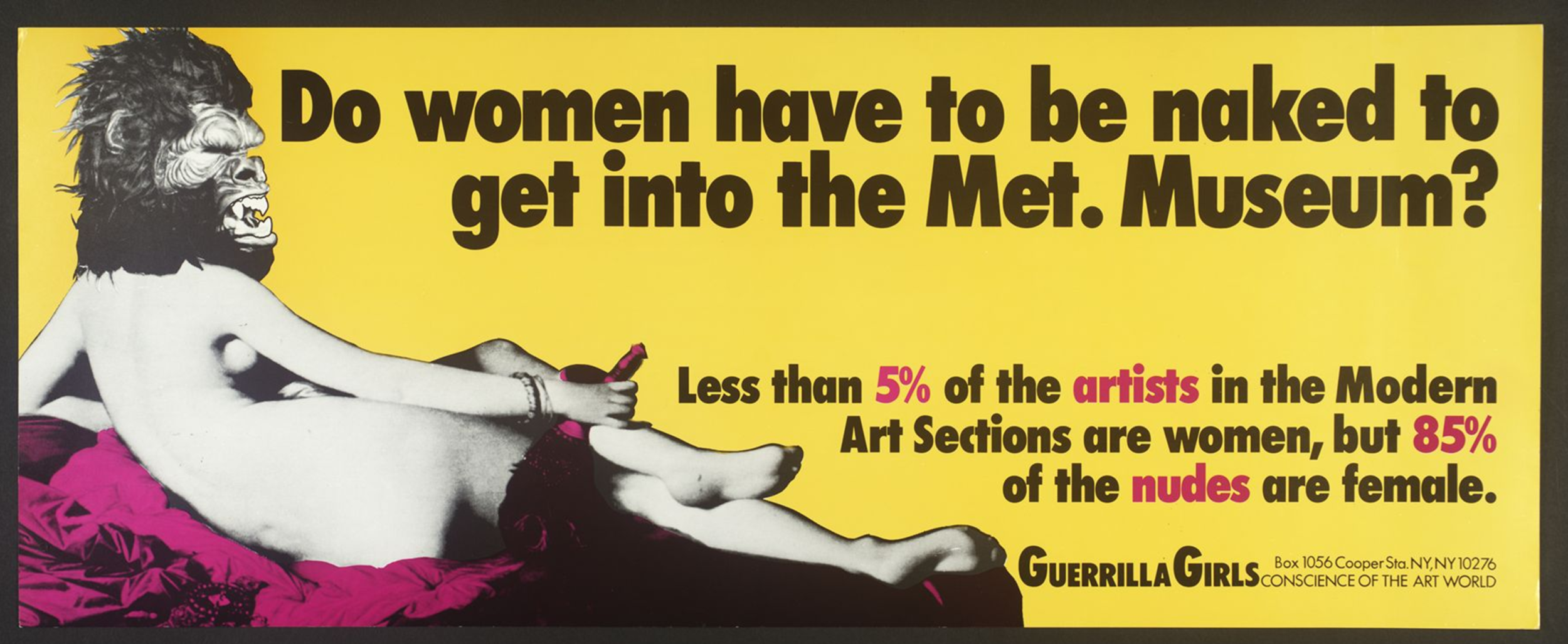

Art history is filled with men making objects of the female form. They range from the (supposedly) ideal (Alexandros of Antioch’s Venus de Milo), to the (clearly) confused (Michelangelo’s Night), to the (infantilized) ingénue (Degas’ Little Dancer Aged Fourteen). The Gorilla Girls had confronted that reality — I wanted to control that reality. In my version, I would be making my own body: rather than ideal, it would be honest, rather than confused, it would be articulate, and rather than ingénue, it would be woke.

So, lying on the floor of my studio, collapsed like a damsel in distress with two men assuring me of my physicality, was not exactly what I had had in mind. They were holding me, and since I was still cloaked in my mold, they were holding my sculpture.

I had wanted to intercept the male gaze. To snag the eyes of my viewer and direct his gaze explicitly upon my self. I could escape his‘capture’ by first capturing my own self. To do this would be quite empowering. I would become both model and maker in a self portrait that would make solid what is normally so pliable: my body.

For years, in my studio, I had been battling this ‘pliability’ of my body. As a seamstress, nearly all of the garments that I make are made for my body. Now, I needed to make myself to make for myself. Not only would this self-portrait render me visually, as an image, but it would render me physically, as an object. To replicate my body with the desire of seeing myself from the outside was an attempt to relocate my own physicality into a static object — a static object that I then intended to re-make as pliable by using it.

I had never been the model for a body cast. The more silicone they slathered on, the more dressed I felt. When we dress ourselves, when we express ourselves through clothing, we frame ourselves. Without this “us,” we are merely framing a void. Why else do we line garments with soft, silky fabric? Linings are an acknowledgement of the body within a garment. To deny the personification of that space is to deny the very thing that makes garments unique — their ability to hold, to contain, and ultimately, to enhance, a life.

The process of casting is the process of moving between positive forms and negative forms. You must twist your mind to think in three-dimensional negativity. If my body is a positive, then the silicone and plaster that went on it was its negative. The next step was to turn that negative back into a positive.

A few days and a lot of electrolytes later, I used fiberglass netting and a plaster-like material called Jesmonite, to turn my negative body cast back into a positive. Life casting is never perfect so there was a lot to “fix.” Much like 3D photoshopping, I set about ‘correcting’ these mishaps.

The spatula that Simon had used to apply the silicone had gotten a little wonky near my stomach, leaving air pockets at my belly button. I carved these away with a Dremel, an electric carving tool just like the one your dentist uses. My left breast had collapsed — so I had to fill that in. I called it aspirational sculpting. The fainting, and the subsequent time spent on my back looking up at Simon’s upside down face, had caused the curve of my spine to become extended, so I had to shave that down. And then, truly testing my self-esteem, my left butt cheek had become severely indented. I spent six hours filling out my butt cheek, making it bigger to match the other side.

“All throughout, as I filled in and carved away, I was touching my own fleshy body for confirmation. That left breast had collapsed in a way that looked quite natural — was it really a mistake? Or was my left boob just kind of funny shaped?”

All throughout, as I filled in and carved away, I was touching my own fleshy body for confirmation. That left breast had collapsed in a way that looked quite natural — was it really a mistake? Or was my left boob just kind of funny shaped? If I could have Dremel-ed shirtless, it would have saved time and trips down the hall to the bathroom mirror.

But the bathroom mirror began to feel a little redundant. I was working in a semi-public studio with other artists working around me. Should I be embarrassed? Shy? Did I really need to run to a private space to take my shirt off to check my shape? Wasn't that kind of pointless, given that my naked body was on display already? Was there a difference between a gaze upon my rigid body and the gaze upon my fleshy pliant body?

Having worked in the fashion industry from age 14-19 as an intern for a major womenswear designer, my adolescence was spent standing next to models as they put on and took off clothing. Nudity was not something to be ashamed of or hidden — it was merely what the model had on under the garment we gave her. Nudity was merely a fact — a truth; maybe even a truth that garments could only hope to achieve. Between this and learning to figure draw from nudes, I was very comfortable, professionally, with the naked body.

But it’s easy to feel confident in your own nudity while standing upright with color in your face. It’s less easy to feel that same confidence having just passed out, with a little drool on your cheek, and having to crawl out of a silicone mold like a wingless caterpillar trapped on the ground.

As I carved and filled my body, the type of dress form I was looking to make dictated many of my sculptural moves: from the sever of the head and arms to the smoothing of the pelvic region. The more I sculpted, the more Grecian and classical the form became. Every ‘flaw’ on my rigid body propelled the object deeper and deeper into the art historical canon. The hunch of my back brought placed her next to Venus de Milo; the paunch in my stomach was reminiscent of Botticelli’s Eve; even the cellulite on my butt began to endear itself to me as Rubenesque.

Cutting off my legs at the wide point of my thighs created a strong, stable base and made my waist appear quite tiny. The shapes on my body felt natural, real, and unusual but honest. In figure drawing, you are taught to trust your eyes. Carving this form, I was forced to trust my hands. I would close my eyes and put one hand on the plaster and one hand on my skin to compare.

Once I finished this Jesmonite positive, I had to make the form in foam. To do this, I had to recast it in a negative in order to create a mold into which I could cast foam. I chose a foam that was sturdy enough to hold its shape, yet soft enough to take a dress pin.

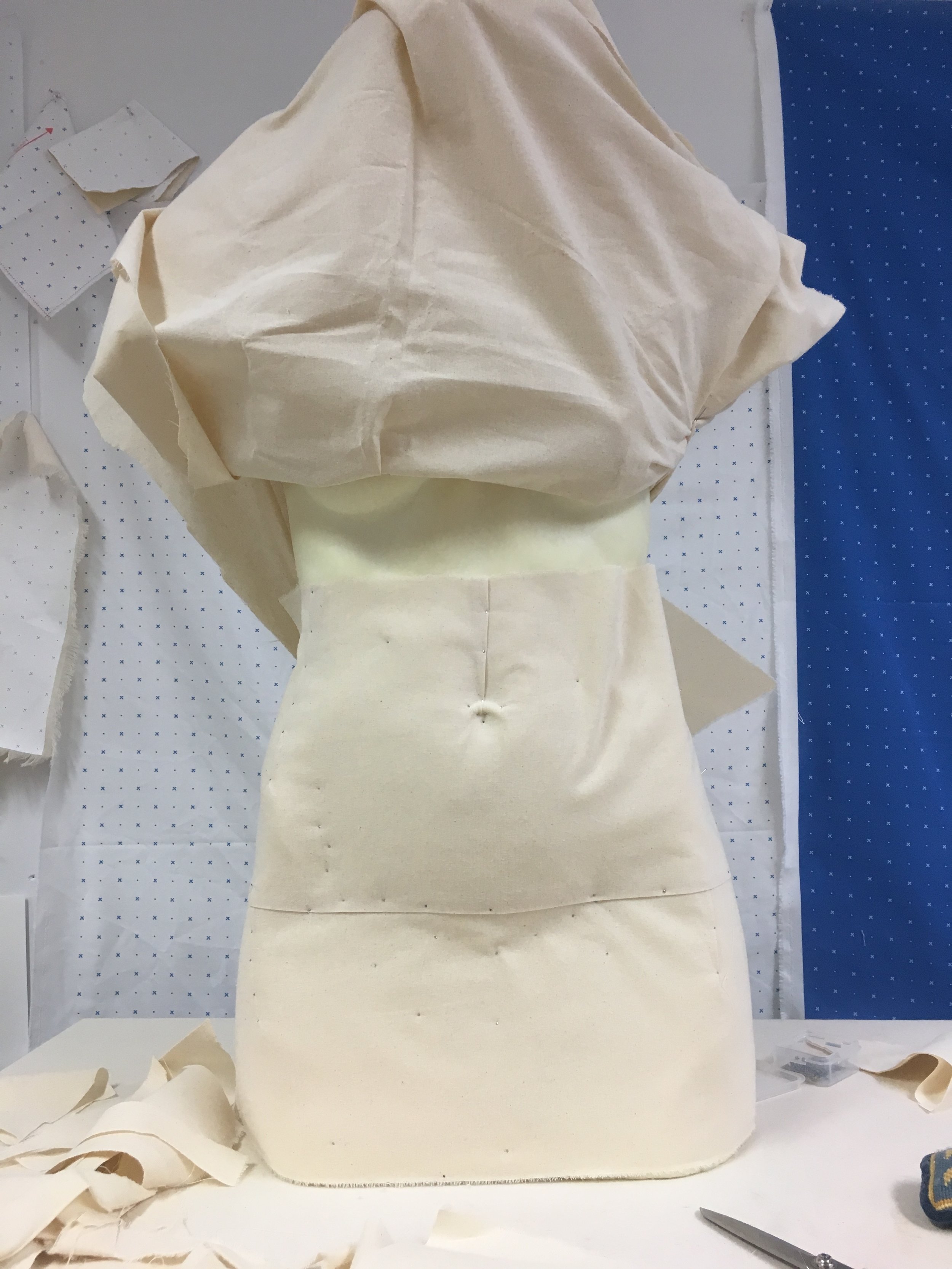

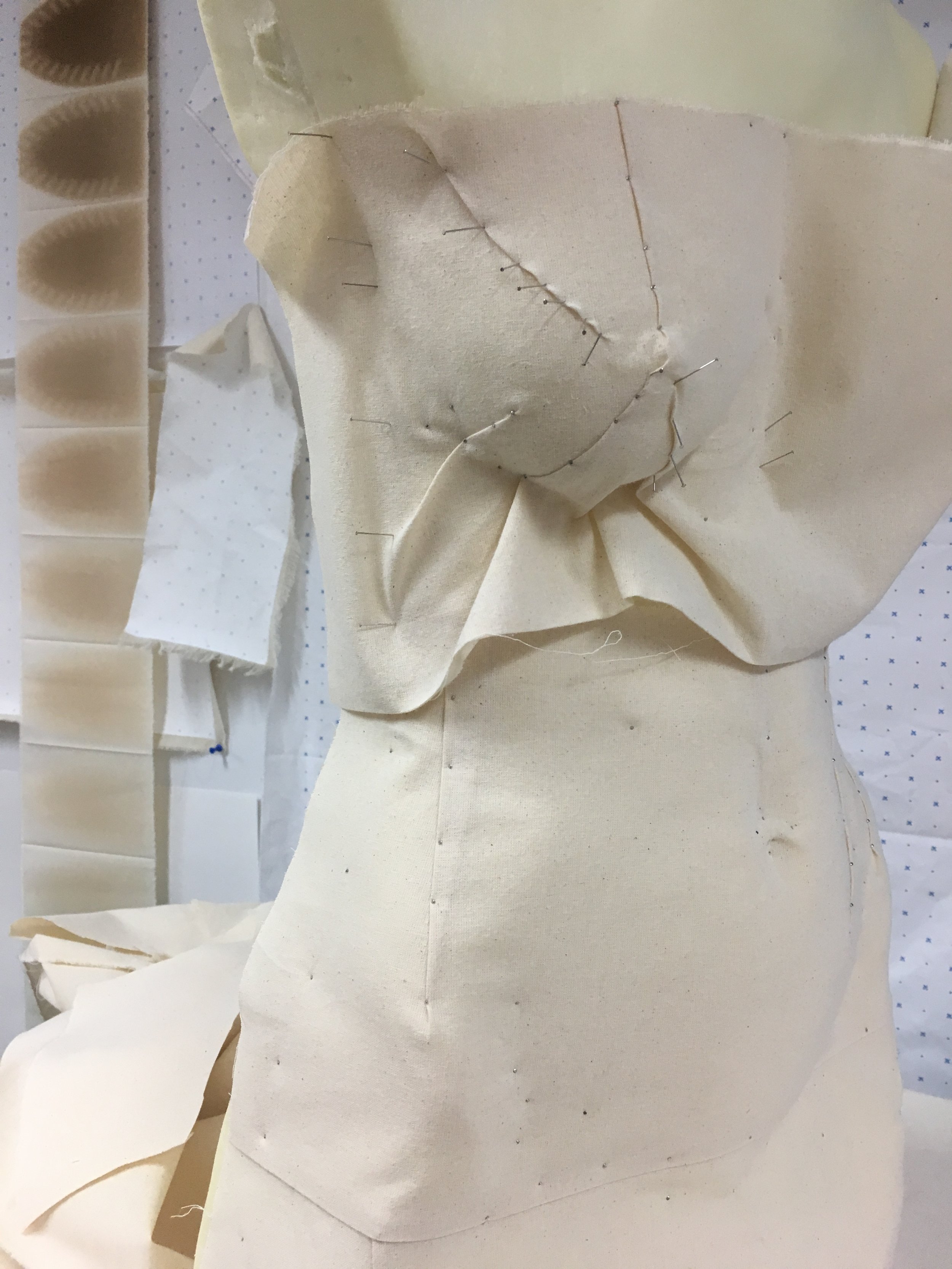

Once I had the finished the foam form, I set about draping a muslin covering for it. By this point in the process, I was intimately aware of the shapes on my body. I draped over my belly button and up my torso. The complex curves of my bust proved the most difficult. Nothing on my body was symmetrical and the draping reflected that fact. My method was simple: let the fabric do as it wished. Lean in to the fabric and the curves. The more I leaned in, the more interesting my shapes and drapes became.

As I draped, I pinned each fold into the foam. I went through hundreds of pins as the skin on my fingers grew weak, pressing the pins deep into my foam form.

I finished the form by impaling her on a traditional steel stand. By then, I had begun to call the form ‘her.’ I would carry her around the studio on my hip and would talk about her like a friend, or a houseguest. Happy to host, but dear god she was a lot of work.

The form was useable, but fragile. In making her, I had turned her into a sculpture. Today, she feels too precious to use in the aggressive way that I am used to using a dress form. When she was just plaster, I would carve into her with an electric saw. When she was just foam, I would accidentally drop her on the floor, giggling, horrified, as she bounced off her nipples. But when she was finished and covered in muslin, all neatly tucked in, she looked clothed, dressed, ready to be seen in the world. I am hesitant to ruin her outfit.