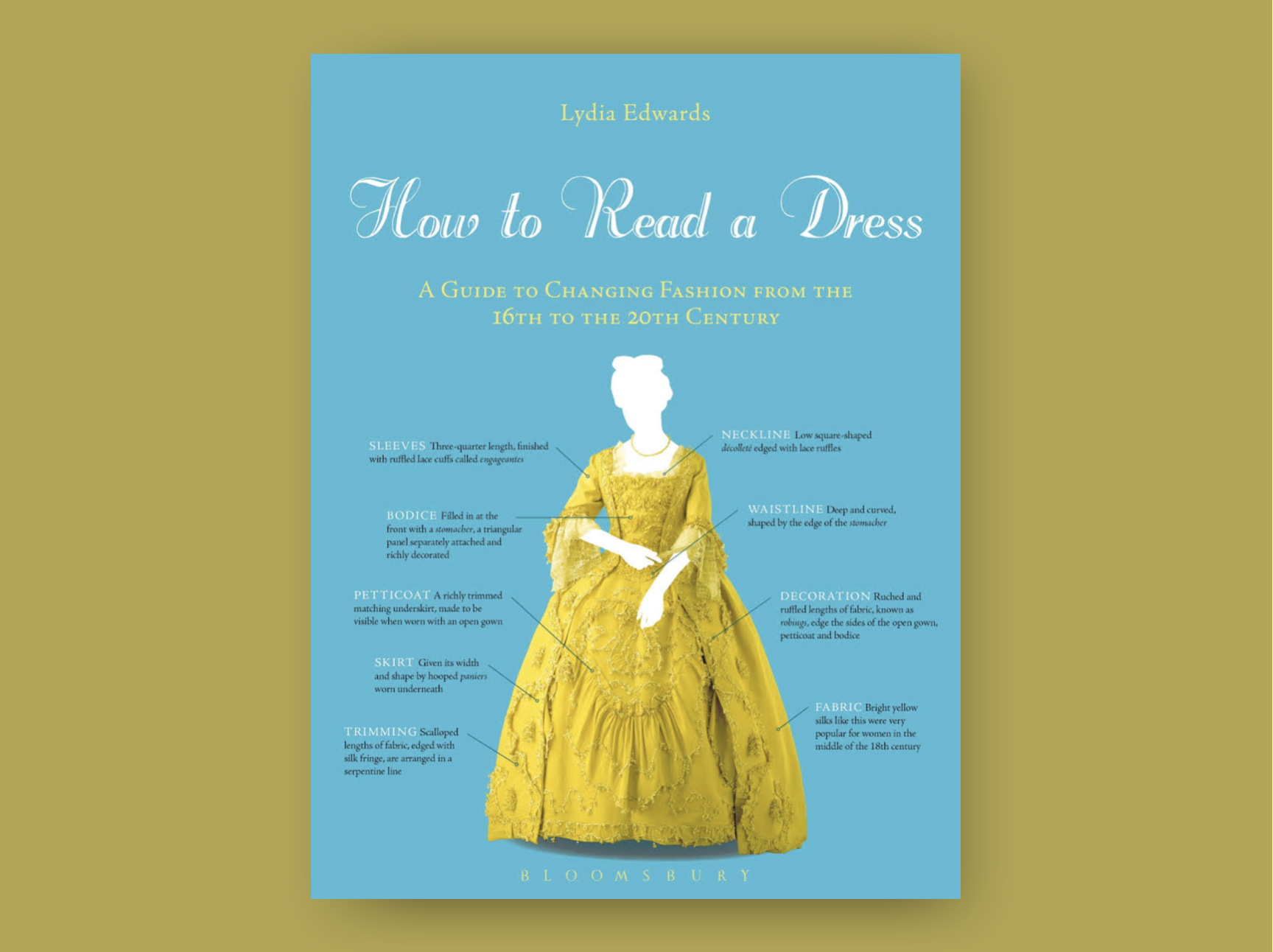

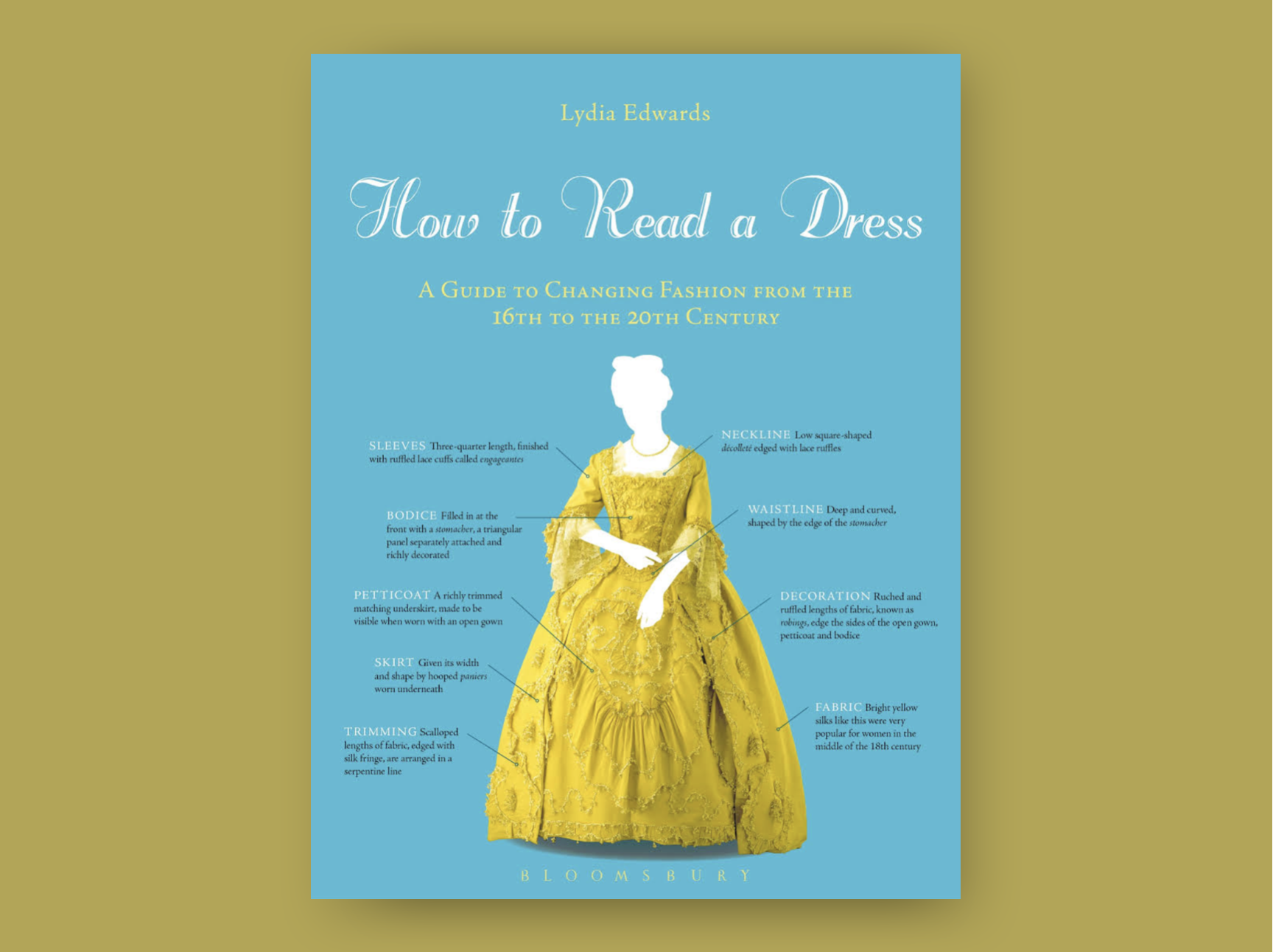

How to Read a Dress

Lydia Edwards, How to Read a Dress: A Guide to Changing Fashion from the 16th to the 20th Century, Bloomsbury, £75.00, 216 pp., September 2017

A chronology of fashionable change is one of the most useful tools for getting acquainted with the history of dress, but it is no doubt one of the hardest things to compose. Dig deep enough into the archives and you’re sure to find an exception to every rule, old garments re-purposed, anachronistic styles assumed by portrait subjects, and regional variations, even within the limited western tradition. Lydia Edwards, a lecturer at Edith Cowan University in Perth, Australia, has recently contributed another volume charting an evolutionary fashion narrative. How To Read A Dress is a visual analysis of dress, women’s dresses in costume collections specifically, from the sixteenth to twentieth centuries.

The book breaks down its extensive timeframe into eleven chapters, concluding in 1970 where the author claims, and most scholars would agree, fashion became more pluralistic and the dress as a garment was merely one option out of many, and not a staple item. The chapters generally correspond to shifts in the overall silhouette, but in style, as in life, things don’t always line up in a tidy fashion. Chapter 6, for instance, covers 1790 – 1837 beginning with the neoclassicism of Les Merveilleuses and ending with the voluminous structured gowns of the Victorian era. The aesthetics are worlds apart, and while the author does address the paradigm shift I wish more time was spent examining the how’s and why’s. It’s not a comprehensive cultural history, but the text still offers plenty to think about; each chapter beings with a concise essay summarizing the key historical changes, and how they are embodied in the clothing, through silhouette, materials, and construction.

The book’s greatest strength lies in the meticulous attention to detail in the analysis of each garment. Reading the visual cues is the goal, and garments are illustrated with bullet points noting details in their fabrication and decoration. They are sequenced so that the reader can compare within and across chapters to trace gradual changes as well as the persistence and re-imagining of styles and accessories. The careful focus on the material itself is a welcome contribution to the literature, especially at a time when theoretical interpretations in fashion studies risk obscuring the garment itself. Her analysis demonstrates the depth of information contained in each dress, and while they fit into a chronology, unique idiosyncrasies breathe individuality into each piece. I particularly appreciate the inclusion of previously unpublished examples from collections in Canada, Australia, Italy, and the Czech Republic. It helps the reader grasp a more inclusive history of fashion, and to see how styles communicated internationally. It’s also just nice to look beyond the fantastic, but very well documented collections, in London, New York, or Paris.

How to Read a Dress could be a helpful tool in teaching the history of costume because the clear format directs the eye towards design details – the height of the waist, length of sleeve, bodice shape, etc… that help situate a garment historically. It rewards looking closely and seeking information directly from the garments. However, I don’t think it would be useful for an introductory course.

The level of detail and knowledge of textile techniques and terminology is quite advanced, and the text is written for an informed reader. For example, Chapter 2 (1610- 1699), makes reference to Cromwell’s Protectorate in Britain, assuming the reader is familiar with the political context and the accompanying Puritan ideals. I know from experience, at least with undergraduates in the United States, that this is rarely the case. The author will also occasionally make reference to menswear from a corresponding period, but without accompanying examples, these references might be lost to readers new to costume history. Yet taken as a whole, those looking for a detailed, object centered and carefully researched study of historic dress will find a satisfying, richly illustrated guide for looking at clothes.