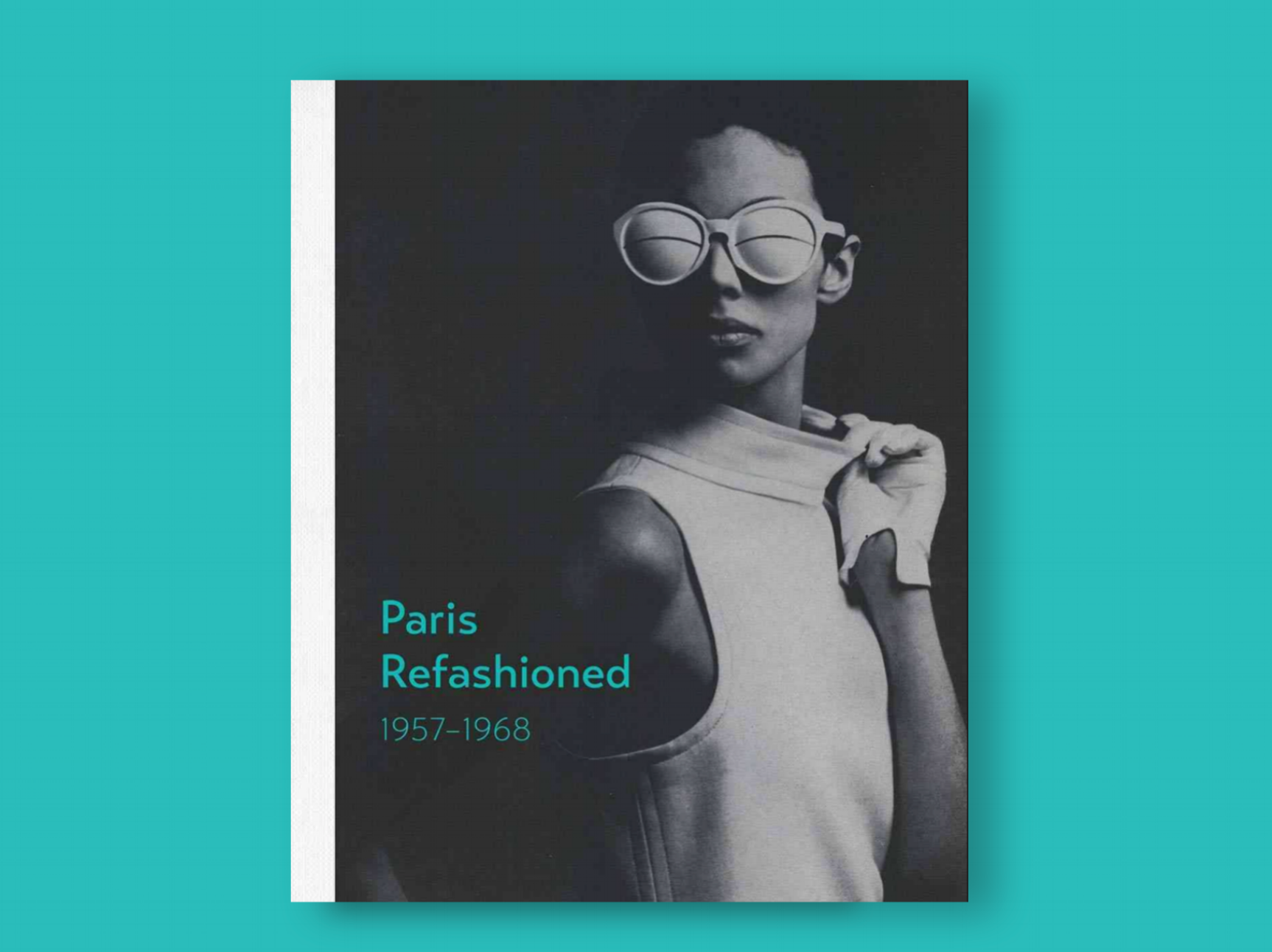

Paris Refashioned: 1957-1968

Colleen Hill, Paris Refashioned: 1957-1968, Yale University Press, $55, 252 pp., February 2017

A coffee table book is a book that is designed to be looked at. It is an object in its own right, lavishly illustrated with an emphasis on pictures rather than words, physically large and heavy, and so difficult to hold, with glossy pages that look expensive but which also reflect the light – both features that make reading difficult.

This is a coffee table book.

Which is a shame, because the content is actually worth reading. It is well beyond the superficiality one usually associates with coffee table books. The purpose of the book is to study the period in which prêt-a-porter overtook haute couture as the dominant mode of fashion. The point being made is that, while the French did not invent prêt-a-porter, they nevertheless were not stuck in an aging and increasingly irrelevant couture-based approach. That said, a discussion of prêt-a-porter only appears after a hundred pages devoted to notable couturiers of the time. Likewise, the observation that the French may have invented haute couture but they were not responsible for prêt-a-porter begs the unanswered question, “well, who was?” (My guess is the Italians, in the 1950s, followed by the Brits with Quant, Biba and the Swinging London phenomenon in the early-mid 1960s.)

Following on, as it does, from an exhibition of the same name that took place at the Museum at FIT in New York in 2017, the thoughtful choice of images reflect the museum’s collection items that were displayed during this show, and each is accompanied by a detailed description of the item shown in the photograph. Thorough and rigorous scholarship leaves little to the imagination here, and the text informs even the most fashion-resistant reader precisely what it is they are looking at. The French couture establishment’s response to the challenge that prêt-a-porter presented is clearly set out, and the reader is guided, piece by piece, through a selection of garments from the big names and heavy hitters that have come to be legends of the fashion world – Dior, Givenchy, Yves Saint Laurent and Chanel are all present and correct here, with careful analyses of their work from the period detailing how they moved from the 1950s to the 1960s, with all that that entails. The author notes that although popular fashion discourse tends to work in decades, fashion itself rarely follows such a neat linearity, and the framing of her project from 1957 to 1968 more closely aligns with cultural events and design developments in and around fashion.

Besides the thorough exposition of Colleen Hill, the volume is augmented by four essays by Valerie Steele, Patricia Mears, Emma McClendon and Alexis Romano, which consider various aspects of French life around the period covered by the exhibition, and which add considerable depth to the detail given by Hill herself.

Steele’s essay, on the événements of May 1968, illustrates the point at which fashion ceased, temporarily, to matter in Paris. The students spent a month tearing up cobblestones to throw at the police while they demonstrated with placards bearing such tautologies as “Be Reasonable – Demand the Impossible.” At the end of the month, of course, all of the cobblestones were put back, minor concessions were made by the government, the Sorbonne university from which the agitators were spawned was restructured into four different colleges, spread across four different parts of Paris, and the city returned to normal. As May 1968 passes ever further into history, the long term impact of the événements seem now to be mainly in the minds of those who participated in them. The French psychoanalyst, Jacques Lacan, wrote that the challenge of the students, far from marking any serious challenge, was an integral part of the dynamics of human relations, and he located it within his theory of the Discourse of the University. The philosopher Michel Foucault likewise pointed out the limited revolutionary potential of such actions, and cited the dearth of true epoch defining, world-changing revolutions that have ever taken place.

“Thorough and rigorous scholarship leaves little to the imagination here, and the text informs even the most fashion-resistant reader precisely what it is they are looking at.”

Mears considers Balenciaga, and in a thorough study of his work and life, in which his creations are described in detail, what emerges is that while fashion may well have an industry that is concerned with selling clothes, there are also some fashions that go beyond a simple matter of clothing, and that has little to do with retail. Balenciaga has historically been one of the designers who has transcended the fashion industry, and whose work places a far greater emphasis on creativity and expression. The canard of fashion is/as art is a well-rehearsed argument that there is no time for me to explore here, but what is significant is the way in which it is possible for some designers to separate fashion as a creative form from fashion as an industry, and Balenciaga is one such designer.

McClendon writes about the success of Yves Saint Laurent’s shops, which he called Rive Gauche – The Left Bank. The Left Bank refers to the side of the river Seine, that runs through Paris, which is associated with bohemians, artists, and, yes, students. It is the location of the Sorbonne, home of the ‘68 demonstrators. What is interesting is the way in which Saint Laurent was able to co-opt the notion of youthful rebellion into a retail strategy that marked him as a part of a new wave of French fashion designers. He moved at the head of the youth quake – or at least, convinced those who could afford his clothes that he was a part of the radical new youth movement and that they could be too, if they bought his clothes. The success of Saint Laurent’s Rive Gauche retail operations, in Paris and elsewhere, attest just as surely as any philosophy or psychoanalytic theory, that the radicalism of the soixante-huiteurs was too familiar to ever be truly revolutionary.

Alexis Romano’s essay contextualises the developments in French fashion in terms of modernity, urban life and the notion of the spectacle. She draws on French cultural theorists Roland Barthes and Guy Debord, both of whom were writing during the 1960s and responding to the events of the time in the same way that fashion was, and makes connections between the theories their writings embodied, and the ways in which fashion operated, and was represented, at the time. Street style became a tangible cultural form long before the phrase was coined in the 1990s, and the process of seeing and being seen is integral both to modern life and to the humans who live it.

To conclude, then, yes, this is a coffee table book – it is too heavy, too glossy, and too image-packed to be otherwise. However, this is actually a distraction from some of the important ideas that are expressed in it. For the fashion historian in particular, this book fills an important gap, and addresses in-depth for the first time what the French were doing while British and Italian fashion were moving into pole fashion position. It deserves a wide readership.