Looking Cool in Black Leather

I can do anything I want, because I look good in leather/I can talk any kind of talk, because I look good in leather.

The above are lyrics from Cody Chesnutt’s hit song, Look Good in Leather, which gets to the heart of many of the clichés associated with wearing leather. In the video, a leather jacket-wearing Chesnutt projects a kind of unflappable confidence that says, “I’m cool with attitude and ego to spare.” It’s certainly no coincidence, however, that Chesnutt links leather with coolness.

The concept of his “black leather coolness” is almost one-hundred years old and can be traced back to the beginning of the 20th century. I stumbled upon this idea while working on my doctoral thesis in German Studies, which focused on the way fashion was written about in essays and novels of the 1920s. In surveying my primary source material, I noticed a discernable tendency amongst some German artists and writers who presented themselves in dark leather jackets in the period following the First World War. In these descriptions, the figures embodied a nonchalant yet confident aura for which I could find no better descriptor than “cool.” During my work lecturing in fashion theory in Berlin and Hanover, my growing interest in the intersections of leather and coolness was further piqued by the global proliferation of young fashion designers describing leather-based looks as cool.

It was against this backdrop that I began my research, presented below, into why we almost automatically associate black leather with coolness. I started analyzing images widely disseminated in the media to see which might be playing a role here while also examining gender stereotypes in connection with black leather clothing. The most fruitful approaches to these questions proved to be an assessment of the leather jacket as a costume in filmic and stage representations, as well as a history of the mentality of coolness.

With the word “cool” completely drained of meaning – used today in an excessive, inflationary way – it seems extraordinary that coolness can still be linked with specific garments and characteristics. Indeed, no other garment has been so continually associated for so long with coolness as the black leather jacket. At once, it is part of the fashion industry’s mass-market repertoire yet, barely having changed form over the last century, it stands as a classic symbol of affectlessness, individuality, and non-conformism. The black leather jacket is worn and loved by punks, indie slackers, and models “off duty” as much as it is by CEO’s who, on the weekends, pose as Wild One-esque bikers. It is the sartorial commodification of cool.

Luxury brands – such as Acne, Rick Owens [1], and Vetements – and fast fashion labels alike trigger the customer’s desire with the promise that buying a leather jacket will let her slip on a nimbus of cool nonchalance. However, the process of exploiting and managing coolness is not only overseen by the fashion industry: The music and film industries are also in the business of perpetuating cool. Through the canon of western film, we’ve gotten to know teenage wannabe James Deans, arty freaks, broken anti-heroes, detectives, and hackers – all of whom donned black leather. The leather jacket has become a sort of shorthand for “outsider.” Leather-clad characters, film-makers imply, cannot be integrated into the matrix of a hegemonic system. Wearing leather jackets marks characters out as drivers of suspense.

Permanently balancing conformity with non-conformity and life with death, these leather-wearing archetypes generate a sense of genuine adventure rather than the soft atmosphere of sickly-sweet romance. As part of the style arsenal of a “fashion of evil” [2] linked to the Metal, Gothic, and S&M scenes and their many symbols related to death, the black leather jacket is a visual and sartorial rejection of upright, civic moral codes. Dressed in this universal symbol of anti-authoritarianism, these cool film characters are not only capable of defying the customs of polite, civil society; they also embody an attitude more strongly associated with masculinity than femininity. While many women today employ leather jackets to embody a sort of detached affectless – a quintessential element of the “I don’t care” look – the coolness they evoke exudes a subtle, but undeniable, boyishness linked to the garment’s origins. Indeed, a peek into the archives of leather fashion and youth culture as well as the history of coolness reveals that this is male-dominated territory. Glancing through the official Berlin state archives’ collection of fanzines covering youth culture, for instance, it is immediately clear that, with few exceptions, the vast majority of icons from rock and roll through to hardcore metal are male, as are the young rebels depicted in media coverage of youth protests. The relationship between coolness and leather, however, demands a deeper analysis – one that transcends the twentieth century’s cult of cool.

Historical Origins of Cool

Researchers attempting to trace the history of coolness have examined not only historical sources for early references to the term “cool” but have also focused on many different countries.[3] Studies show that the origins of cool lie neither with one particular person nor one place. Cool attitudes seem to have been around long before the appearance of Miles Davis’s Birth of the Cool. While some analysts believe they have traced the origins of coolness to West African tribal cultures, Jamaica or Japanese Samurai traditions, others maintain that it harks all the way back to the Stoics of ancient Greece.[4]

We may assume that coolness is a multi-layered concept that is always evolving and always in transit; it is a concept that cannot be attributed to a certain period, country or even gender. Rather, it must be seen through the prism of a flexible, multifarious kaleidoscope of meaning stemming from a variety of international, multi-racial influences and contexts. This being said, coolness also shows some stable attributes. It almost always refers to an attitude of “keeping a cool head” in moments of stress or strife. Agents seen as cool have an aura of autonomy, dignity and distance, thereby distinguishing themselves from the masses. This aura is often reminiscent of a diva or a proud warrior. Nonchalance, a sense of defensive reserve and the capacity for resistance are not contradictory here. Arenas marked by competitive struggle and conflict often serve as the background to this specific demeanor. Within this context, it is possible to understand coolness as a survival strategy.

The period between the two world wars saw an emphasis on variations of a certain facet of coolness, namely a belligerent, warlike attitude. This aspect is overwhelmingly male because the culture of combat was shaped by men for centuries. Published in 1924, an essay by sociologist Helmuth Plessner entitled The Limits of Community describes the characteristics of a cool attitude in the context of a culture of distance. [5] Echoing Georg Simmel in his 1903 description of the blasé attitude of the modern city-dweller [6], Plessner asserts that individuals living in an urbanized world require artificial and elaborate ways of maintaining distance in order to protect themselves from stress, challenges and degradation. His analysis portrays a society constantly on the verge of becoming a battleground. [7] This portrayal is strongly influenced by experiences of World War I that served as a mnemonic backdrop to the development of a cool, detached sense of disillusionment. And even though the United States was comparatively unscathed by the ravages of World War I, similar processes could be observed in 1920s America. [8]

Cool Meets Leather: Machine Age Aesthetics

In this context, leather garments became a sort of shield, or a suit of armor. Indeed, “battle-ready” cool styles often have their source in the non-idyllic. They emerge from the practice of “self-fashioning” which is used to defend freedoms and sovereignty that are often won in the face of fierce resistance. [9] In a life marked by continual struggle, the performativity of “doing coolness” morphs into an assertive – and sometimes subversive – mode of play with the vocabulary of fashion. Yet this play is neither arbitrary nor random. Rather, it can be seen as non-verbal storytelling that sets itself apart from known looks and imaginings by adapting and quoting from them.

Interestingly, many fashion phenomena still considered among the classic inventory of cool – bomber jackets, camouflage patterns, parkas, trench coats, pilot sunglasses, and, above all, the black leather jacket – were defined in the context of battles or other venues of competition. At the turn of the twentieth century, outer clothing made of leather was mainly worn in situations near oil or gravel as a protective layer.

The people who first dared to drive cars and fly planes were often men, who then bathed in the adulation of crowds at races and rallies, and enjoyed being regarded as heroes. This was one of the ways in which the field of motor sports was, from early on, defined as a male-dominated arena. [10] Thus, it must have seemed all the more unusual to contemporaries who witnessed more and more women entering the rough milieu of roaring machines, taking the wheel both in a literal and implied context of control over their own lives. Appropriately enough, first female car drivers in Germany were called “self-drivers” or “amazons.” Ruth Landshoff-Yorck, an intellectual it-girl of 1920s Berlin, described herself and her female friends – a group including writers like Erika Mann and Annemarie Schwarzenbach – as “girl drivers” in fashion magazine Die Dame (“The Lady”). [11] These garçonnes didn’t want to be seen as ladies who were to be helped into their coats, and they didn’t want anyone “to bend down if they drop something.” [12] Many men were confused by their behavior and demeanor. This is evident in the reactions of many contemporary writers who saw the “girl drivers” as threatening figures and female machine warriors devoid of emotion. The novelist Georg von der Vring complained that the garçonnes’ short hair, leather suits and intention to “govern machines” meant they wrote in “a brutal hand.” He advised them to be “more astute in advertising themselves.” [13]

Overall, motor sports in the nascent twentieth century were a space of mobility which nurtured not only new fashions but also new bodily techniques. Steering a vehicle in the air or on a road required rationality, control over one’s emotions and a willingness to take risks as well as acting and reacting in a level-headed way. These are also characteristics of a coolness with war-like connotations. Interestingly, these properties are also linked to the form-follows-function design ethos of the Bauhaus movement and the design of new military uniforms in the 1920s. This is particularly well demonstrated by the example of a 1930 article that appeared in the Frankfurter Zeitung entitled Leather and Fashion by Siegfried Kracauer. The essay concerns the International Leather Expo in Berlin. Its author asserts that most artifacts presented there are military items. From the perspective of modern leather apparel, he refers to a change in the aesthetics of military equipment, which he describes as sober and sturdy. In Kracauer’s opinion, the minimalist language of form illustrates a transition in the modern combat environment away from romantic ideas. In his analysis, romantic and therefore outdated design elements include those denoting intricate craftsmanship. “While military instruments were once highly decorated, today one takes an exceedingly prosaic approach.” [14]

Leather in Wartime

The black leather jacket is perhaps the single clearest expression during the Weimar Republic of Kracauer’s description of an aesthetic of cool sobriety. This aesthetic was made world-famous during the First World War by the German Luftwaffe. From 1916, German pilots wore black leather jackets and leather overcoats in combination with leg protectors, leather helmets, protective goggles and gloves lined with fur. This attire helped differentiate these elite units from the masses of grey-clothed ground troops. On one hand, it was primarily functional aspects of these garments as providing protection and warmth that led pilots to prefer leather. As a material taken from animals, however, it also exuded a martial quality that commanded respect. Before humans dressed in textile fabrics, they wore animal hides that carried an additional meaning as trophies. [15] Wearing leather has always been connected with death and expresses the desire to transfer the strength of the dead animal to its wearer. Leather thus also symbolizes an archaic brutality. As the uniform of the air forces, it conveys the glamour of danger and the solitary fighter. This becomes especially clear when we consider that pilots, in contrast to infantry soldiers whose identities dissolved into the mass of a large army, remained individually identifiable as heroes of the skies. Black leather jackets were not part of the Luftwaffe’s official uniform during the First World War, making them seem even less conformist. [16]

The black leather jacket first achieved world fame through German flying ace Manfred von Richthofen, whose extremely aggressive tactics and breakneck maneuvers resulted in the “Red Baron” being adored by the Germans and feared by the Allies. Von Richthofen became the subject of a veritable mass cult reminiscent of today’s phenomenon of the superstar. Appearing in 1917, his autobiography The Red Fighter Pilot also contributed to the aura of mystery that surrounded him. Unbridled in its glorification of war, this memoir depicts its author as a cowboy, a prototype of cool continually balancing on a knife-edge between life and death, order and anarchy, law and self-empowerment. Richthofen’s account is pointedly calm in recounting anecdotes of feats accomplished alone and life-threatening situations, while making no mention of worries or fears. Instead, he often highlights his clothing and its outer surface. “Once a bullet went through both my fur-lined boots, another through my scarf, yet another through the fur in the sleeve of my leather jacket, but they never touched me.” [17] These accounts combine with photographs in the media that, taken together, depict Richthofen and his Kameraden as invulnerable hard boys – their rakishly angled caps and leather jacket perpetuating the collective memory, their brand of coolness irrevocably grounded in military aesthetics.

As late as 1985, rock musician Mick Farren of the band The Deviants traced the coolness associated with the black leather jacket back, among others, to Manfred von Richthofen and his pilots, saying, “The problem was that they looked so damn cool” – his definition grounded in the dark, demonic visages of leather-clad German pilots and the Nazis. [18] Like Farren, many young people in Britain and America wanted to appear dangerous and vicious as way of shocking the establishment, appropriating the clothing of the former enemy to do so as effectively as possible. In her essay Fascinating Fascism, Susan Sontag maintains that the Nazis’ leather apparel proved irresistible for many different cultural scenes because it was so well cut. [19] Valerie Steele, too, points to the central role played by the military in the development of the attraction of black leather as a means of provocation, a factor, she asserts, that arose due to a German influence on fashion history. [20] Although the black leather jacket has been regularly been reinterpreted during the twentieth century – by the rockers, Black Panthers, punks or New Wavers, to name but a few – its attraction for most groups has been grounded in its connotations of violence and power. Yet it also has a magical function akin to knight’s armor in the contest for respect, recognition, and in distinguishing oneself from others. It provides the means for even the slightest of youths to become invincible street gang protagonists. [21]

The Flowering of Coolness

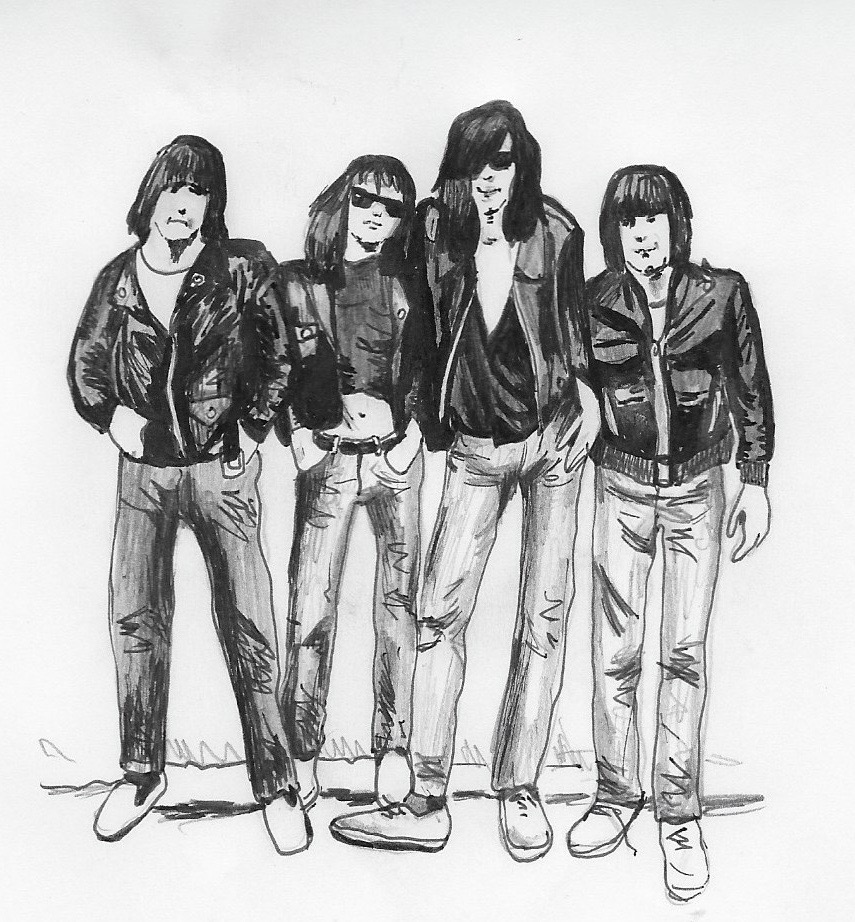

The black dress of the fighter pilot was further developed in the USA in the period following the First World War. In 1928, the American Irving Schott created the Perfecto jacket. Almost unchanged in its design to the present day, this bikers’ jacket is made from Nappa leather and features a silver asymmetric zip, rivet snaps on the lapel and a wide belt to protect the region around the kidneys. Today, a glimpse of this piece of clothing manifests associations amounting to a ‘who’s who’ of cool, ranging from Marlon Brando, Patti Smith, Lou Reed, The Ramones and Sex Pistols through to rockers Black Rebel Motorcycle Club.

The flowering of coolness in the inter-war period can be traced to the period between 1927 and 1928. This phase that saw the invention of a legendary biker jacket and the appearance of Marcus Garvey’s “Keep Cool” slogan, which Garvey intended as advice for his brothers and sisters in the black community as a source of empowerment in the struggle against racism and discrimination. [22] 1927 also saw the production of Sergei Eisenstein’s October, in which the black leather jacket is charged with additional meaning as a visual cipher for the communist revolution, with Lenin depicted in the film wearing dark leather. In the same year, Bertolt Brecht’s self-presentation as a rebellious artist helped raise awareness of black leather as the outfit of choice for leftist, non-conformist intellectuals. Brecht cleverly played with a variety of meanings and connotations for the leather jacket that arose through its use by pilots and leftist revolutionaries. These include a portrait by the painter Rudolf Schlichter, where he is shown dressed in leather with an industrial backdrop in the background, as well as photographs taken by Konrad Reßler of Brecht wearing a leather overcoat and smoking a cigar. These images show Brecht as a bohemian whose poses make clear his contempt for the bourgeoisie and its literary icons. At the same time, his poetry about driving cars evoked the Futurist symbiosis of man and machine in a way that seems apt for depictions of Brecht as a cool, heroic motorist.

In their use of leather, Brecht and his associates developed a threatening, militaristic stance, a poise encoded into the surface of the material they wore. Yet rather than suggesting rowdy aggression, it implied a calm spirit of resistance. It may, however, chiefly have been an attempt to disguise vulnerability.This strategy is demonstrated by Marieluise Fleißer, a friend of Brecht’s, in her novel Mehlreisende Frieda Geier. [23] The eponymous protagonist Frieda masks her vulnerability by wearing a black leather jacket to assert herself in a male-dominated world of car-driving salesmen. As a “girl driver,” she leaves the “classically female” sphere behind – a world associated with living rooms, warmth and an emphasis on emotions. She instead prefers the outside world – the world of the “frosts of freedom.” [24] These “frosts of freedom” refer to an industrialized and conventionally male-dominated world of technology, competitive struggle and daring bravado. In this glacier-like cosmos, Frieda learns to camouflage her feelings and present herself as confident and assertive. With a distant gaze that evinces coldness, she both confuses and fascinates her environment. It seems highly significant that when she revised her novel, Fleißer replaced the word “cold” with the term “non-female.” This edit makes clear how closely notions such as coldness, cool and independence were associated with masculinity in the 1920s, and how strongly they were conceived as a contrast to femininity.

Throughout this period, the phenomenon of women wearing leather jackets was regarded as exceedingly provocative. Their appearance amounted to a rejection of conventional notions of the feminine and suggested a lifestyle in opposition to traditional civic values. It comes, then, as no surprise when Frieda is denounced as a witch by her lover’s conservative mother. The mother can only make sense of her son’s attraction to this female car driver if the garçonne is in league with the dark forces of evil. Even Frieda’s lover, at first captivated by her otherness, later sees in her an ambassador of Satan when she refuses to subjugate herself to him. Seen in this light, Frieda’s “wicked” leather clothing is not only connoted with an atmosphere of freedom and the coolness of motor sports: It also symbolizes something dissonant that cannot be integrated into a traditional, harmonious order.

Centred on Berlin during the Weimar Republic, the “asphalt cool” paradigmatically embodied by Brecht and Fleißer was destroyed only a few years later by the Nazis. Here, too, black leather played a central role. It is now the turn of the notorious SS units to don black leather overcoats as a way of expressing their dominance and aggressiveness.

Conclusion

These days, the black leather jacket can suggest many things, including militarism and pacificism, subculture and mainstream, conformity and non-conformity. It can imply a knight’s armor, mark out a rebel, become a second skin, function as a tool for seduction or be the object of fetishistic desire. Especially during the postwar era, black leather has increasingly come to be associated with eroticism. Its dark sheen, suggestive of the demonic and forbidden, imbues it with a lascivious allure. Provocation is often another label for seduction; wearing black leather is a method of deliberately simulating a strong reaction. While this material awakens desire through its haptic sensuality, the associations of black leather with death and strength also insinuate that its wearer is less sexually inhibited. It gives the wearer the appearance of an omnipotent lord of darkness. The stylistic potential for black leather is far from exhausted.

Notes

[1] Elke Gaugele, “Vicious. Rick Owens Re-Birthing des Cool," in Wilde Dinge in Kunst und Design. Aspekte der Alterität seit 1800, ed. Gerald Schröder and Christina Threuter (Bielefeld: Transcript, 2017), 206-221.

[2] Birgit Richard, “„Böse Mode?“ Visuelle und materielle Kulturen der schwarzen Stile Gothic und Black Metal“, in Die Medialität der Mode. Kleidung als kulturelle Praxis. Perspektiven für eine Modewissenschaft, ed. Rainer Wenrich (Bielefeld: Transcript, 2015), 343.

[3] Annette Geiger; Gerald Schröder and Änne Söll, eds., Coolness. Zur Ästhetik einer kulturellen Strategie und Attitüde, (Bielefeld: Transcript, 2010).

[4] Farris Thompson, Aesthetic of the Cool: Afro Atlantic Art and Music (Pittsburgh: Periscope, 2011). See also Ulla Haselstein and Irmela Hijiya-Kirschnereit et al. eds., The Cultural Career of Coolness. Discourses and Practices of Affect Control in European Antiquity, The United States, and Japan (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2013). Dick Pountain and David Robins, Cool Rules. Anatomy of an Attitude (London: Reaktion Books, 2000).

[5] Helmuth Plessner, Grenzen der Gemeinschaft (Bonn: Cohen, 1924).

[6] Georg Simmel, “Die Großstädte und das Geistesleben," in: Die Großstadt, Vorträge und Aufsätze zur Städteausstellung. Jahrbuch der Gehe-Stiftung zu Dresden, ed. Theodor Petermann (Dresden: v. Zahn & Jaensch, 1903), 185-206.

[7] Helmut Lethen, Verhaltenslehren der Kälte. Lebensversuche zwischen den Kriegen (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1994).

[8] Peter N. Stearns, American Cool. Constructing a Twentieth-Century Emotional Style (New York: New York University Press, 1994).

[9] Carol Tulloch, The Birth of Cool: Style Narratives of the African Diaspora (London/New York: Bloomsbury, 2016).

[10] Gabriele Mentges, “Cold, Coldness, Coolness: Remarks on the Relationship of Dress, Body and Technology,” in Fashion Theory. The Journal of Dress, Body & Culture. Volume 4 Issue 1, ed. Valerie Steele (New York: 2000), 27-47.

[11] Ruth Landshoff-Yorck, “Das Mädchen mit wenig PS," Die Dame, Zweites Novemberheft (1927/28), 12-13.

[12] Ruth Landshoff-Yorck, Klatsch, Ruhm und kleine Feuer. Biographische Impressionen (Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 1997), 162.

[13] Georg von der Vring, “Offensive Frau," in Die Frau von morgen wie wir sie wünschen, ed. Friedrich M. Huebner (Frankfurt am Main: Insel Verlag, 1990), 55-59.

[14] Siegfried Kracauer, “Leder und Mode" in Siegfried Kracauer. Essays, Feuilletons, Rezensionen. 1928-1931, ed. Inka Mülder-Bach (Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2011), 332.

[15] John Carl Flügel, “Psychologie der Kleidung,” in Die Listen der Mode, ed. Silvia Bovenschen (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp,1986), 219.

[16] Nicola Lepp, “Ledermythen. Materialien zu einer Ikonographie der schwarzen Lederjacke," in Österreichische Zeitschrift für Volkskunde. Band 96. (Wien 1993), 477.

[17] Manfred von Richthofen, Der rote Kampfflieger. Die persönlichen Aufzeichnungen des Roten Barons, mit dem „Reglement für Kampfflieger“ und vierzig historischen Abbildungen (Hamburg: Germa-Press, 1990), S. 46.

[18] Mick Farren, The Black Leather Jacket (London: Plexus, 1985), 26.

[19] Susan Sontag, “Fascinating Fascism," The New York Review of Books, February 6, 1975, http://www.nybooks.com/articles/1975/02/06/fascinating-fascism/.

[20] Valerie Steele, Fetisch. Mode, Sex und Macht (Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1998), 160.

[21] Diana Weis, “Die Schwarze Lederjacke. Uniform der Unangepassten," in Cool Aussehen. Mode und Jugendkulturen, ed. Diana Weis (Berlin: Archiv der Jugendkulturen Verlag, 2012) 17-29.

[22] Ted Vincent, Keep Cool. The Black Activists Who Built the Jazz Age (London: Pluto Press, 1995), 131

[23] Marieluise Fleißer, Mehlreisende Frieda Geier (Berlin: Kiepenheuer, 1931).

[24] Marieluise Fleißer, “Avantgarde," in Avantgarde. Erzählungen, ed. Marieluise Fleißer (München: Hanser, 1963), 11.