Readdressing Passivity : Protest Dress in 1960s Civil Rights Photography

On August 9, 2014, one day after the shooting of 18-year-old Michael Brown by white police officer Darren Wilson, civil unrest ignited in Ferguson, Missouri. Armed military was sent to Ferguson as riots ensued. Many of the photographs published during the riots imagine Ferguson as a city on the verge of apocalypse, showing cars and civic buildings on fire as black bodies run through the streets crying and chanting that their lives matter. These photographs are similar to those captured during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s both stylistically and compositionally, and also in that they picture the black body as one that is passive in the face of white aggression. The photographs depict the black body trapped in a state of surrender. To be passive is both a subjected condition and a choice of non-activity. The dominant reading of the black body as pacific in photographs of protest in the face of white violence is harmful because it erases the restraint required to be passive.

There has been a crisis in reading iconic protest and demonstration photographs from the Civil Rights Movement because of a failure to witness or testify. This is a failure on behalf of the spectator who refuses the task of challenging the presentation of history, and blindly accepts dominant narratives regarding the black body as docile, a characterization derived from stereotypes. The typical spectator has not been freed from the masculinist clutches of history; new ways of seeing can only be enacted by a spectator who has been freed from this grip. [1] While the violence against blacks featured in photographs from the 1960s remains intolerable, the dissemination and readings of them have made their consumption bearable. This is because these types of images of white-on-black violence and the victimization of the “passive” black body have become normalized within visual culture. [2] The trope of the docile black body in the face of aggression is a representative device that allows for visual mastery.

While the viewer of these images of violence changes over time, the narrative depicted remains the same. The dominant narrative within the photograph becomes trapped in a cycle of reproduction. Reconsidering the significance and meaning of the civil rights aesthetic archive allows for the rethinking of the image and representation of the black body, which frees it from the grips of hegemonic discourses that try to crystalize it into objecthood.

The photographer as photojournalist dreams that their photographs will incite sociopolitical change by generating an affective response within the viewer. The role of feeling within photographic theory and practice is fundamental with regards to the experience of viewing photographs of suffering or violence because it calls on the viewer to assume the role of secondary witness, or rather a witness who was not present at the moment of incident but develops an emotional identification. [3] The visual experience is never purely visual, but rather engages with other senses that enhance how we see. To discuss feeling in relation to the photographic image is to discuss both the tactile, or the textural, and the emotional. In addressing the symbolic value of dress in relation to the black-body-as-protest-body the viewer gets closer to touching or rediscovering a new narrative of the photograph through the poetics of dress vis-à-vis its aestheticization.

“The aesthetic of resistance within the Civil Rights Movement used wearable political signs, badges, and buttons in almost every public demonstration as a visual and material way of asserting collective beliefs through individual bodies.”

This essay focuses on how interpreting black protestors’ dress practice can change the experience of viewing and ultimately understanding the black body’s role in civil rights protests. Focusing on the material conditions of dress in relation to the activist body and the self-fashioning of the black body through political signage, it will not only be clear how one’s dress practice can be a form of institutional critique, but also will create a new reading of the black body as active within civil rights protest photography.

The aesthetic of resistance within the Civil Rights Movement used wearable political signs, badges, and buttons in almost every public demonstration as a visual and material way of asserting collective beliefs through individual bodies. These forms of protest accessories aided in the construction of a reality that was based on a blending of hopes with the real. [4] Protest dress (conceived of here as political signs made out of simple white poster boards with political slogans and accessories) engages in a public dialogue for equality through creativity. Protest dress did not attempt to threaten American ideals of freedom, liberty, and justice, but rather make visible through critique the effects of disenfranchising systems of power on those government ideals. [5] Using Joanne Eicher’s definition of dress as any modification done to the body, protest signs and accessories enter the space of dress practice. [6] Civil rights protest dress in the form of signs is a way of armoring the body with one’s beliefs by establishing a visual dialogue with the oppressor, and it is also an active demand to be seen and to speak when encountering the possibility of violence.

Signs of Agency

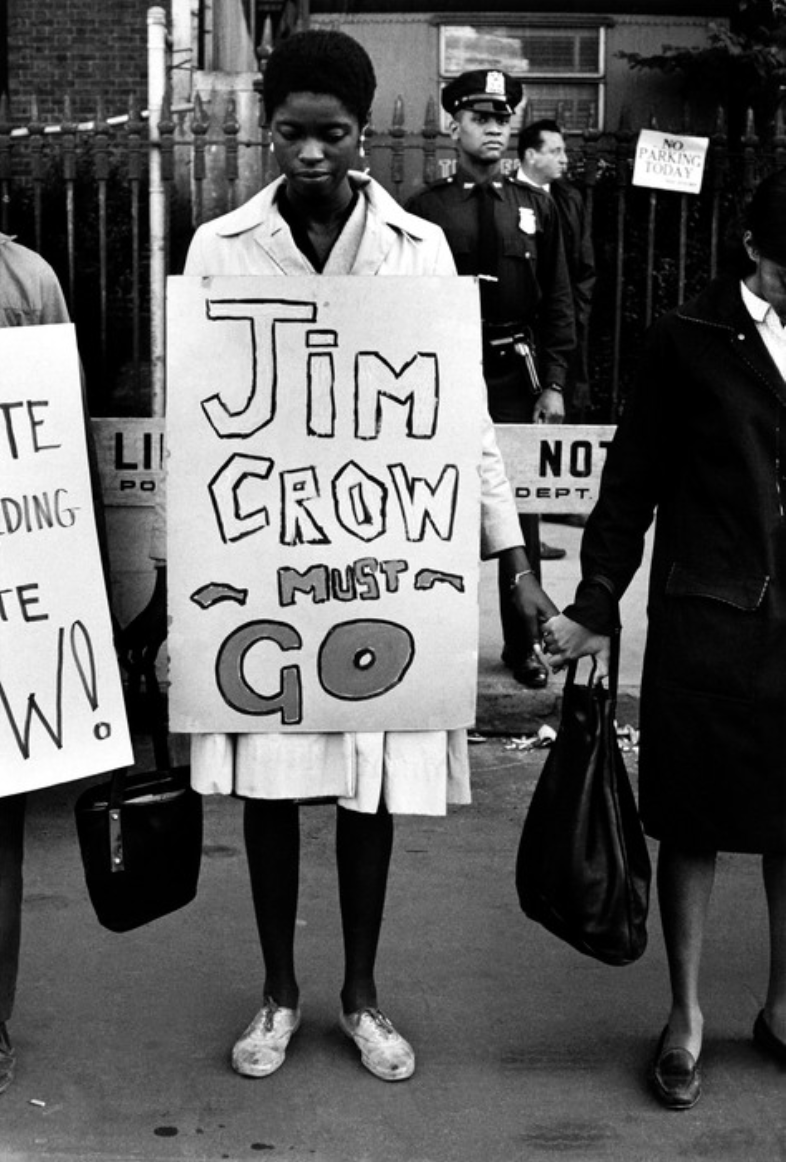

The types of wearable protest signs that emerged during the Civil Rights Movement relied on the stylization of written language as a means of rewriting and challenge how dominant cultural narratives regarding the black body as inactive were inscribed on black-activist bodies. Hanging close to the body, the protest signs acted as a second layer of dress protecting the body from further objectification. Bruce Davidson, an American photographer who documented the socio-political climate of the Civil Rights Movement mainly between 1960-65 in New York City and the Deep South, captured what Deborah Willis calls the, “interiority of the period…intensely observing intimacy and strife.” [7] Davidson’s photograph of a young female demonstrator wearing a “Jim Crow Must Go” sign on the streets of New York City (fig. 1) shows a rejection of the idea of the black body as passive in that she assigns herself as author of not only how her physical body is perceived but also her-self through her poise and expression. Three bodies stand with hands held in solidarity; however, Davidson focuses his camera gaze on the central woman wearing a short afro who directs her eyes downward in an expression of introversion. Behind the sign, she wears what appears to be a trench coat. Her shoes carry scuff marks and show signs of wear, or signs of work. Davidson plays with ideas of marginalization and centrality, or rather how these positions are unstable, through the way the camera frames the scene. The police officer in the background is protected by a barricade: his presence outside of the intimate circle of demonstrators marks his marginalization in relation to the events occurring between the demonstrators in the photograph. He is excluded both physically and symbolically from the scene of peaceful demonstration. While the scene itself is rather static, there is tremendous energy in the figuration of words on the demonstrator’s sign. Her sign is not only a declarative speech act, but also is an active protest against the racial segregation Jim Crow laws imposed in the South that denied African-Americans their civil liberties. [8] There is a crudeness in the jagged rendering of the words she wears that echoes the barbarity of the laws. The juxtaposition of her timid demeanor against the dynamism of the way she styled the words she wears allows for a new reading of her identity within the image. Her image reasserts her place as author of her own identity and meaning. The energy in the stylization and content of the sign the woman wears protects her own intimate sense of self. The central figure engages in a type of body politics vis-à-vis the creation of her own political style narrative, and in doing so she helps rescue the submerged black body from the space of the feminized Other, a concept which emerged in the nineteenth century when the enslaved black body was thought to occupy all body and no mind, which contributed to a devastating loss of political and social agency. [9] While black protestors implemented ideas of comportment and respectability in their everyday dress worn in protest, they also found further expression and liberation in how they chose to use signs-as-dress as subversive critiques of the idea that they needed to be like white Americans in presentation. John Oliver Killens, an African American writer and civil rights activist, wrote in an article for The New York Times in 1964, “We are not fighting for the right to be like you. We respect ourselves too much for that. When we fight for freedom, we mean freedom for us to be black, or brown, and you to be white and yet live together in a free and equal society.” [11]

Disrupting Respectability

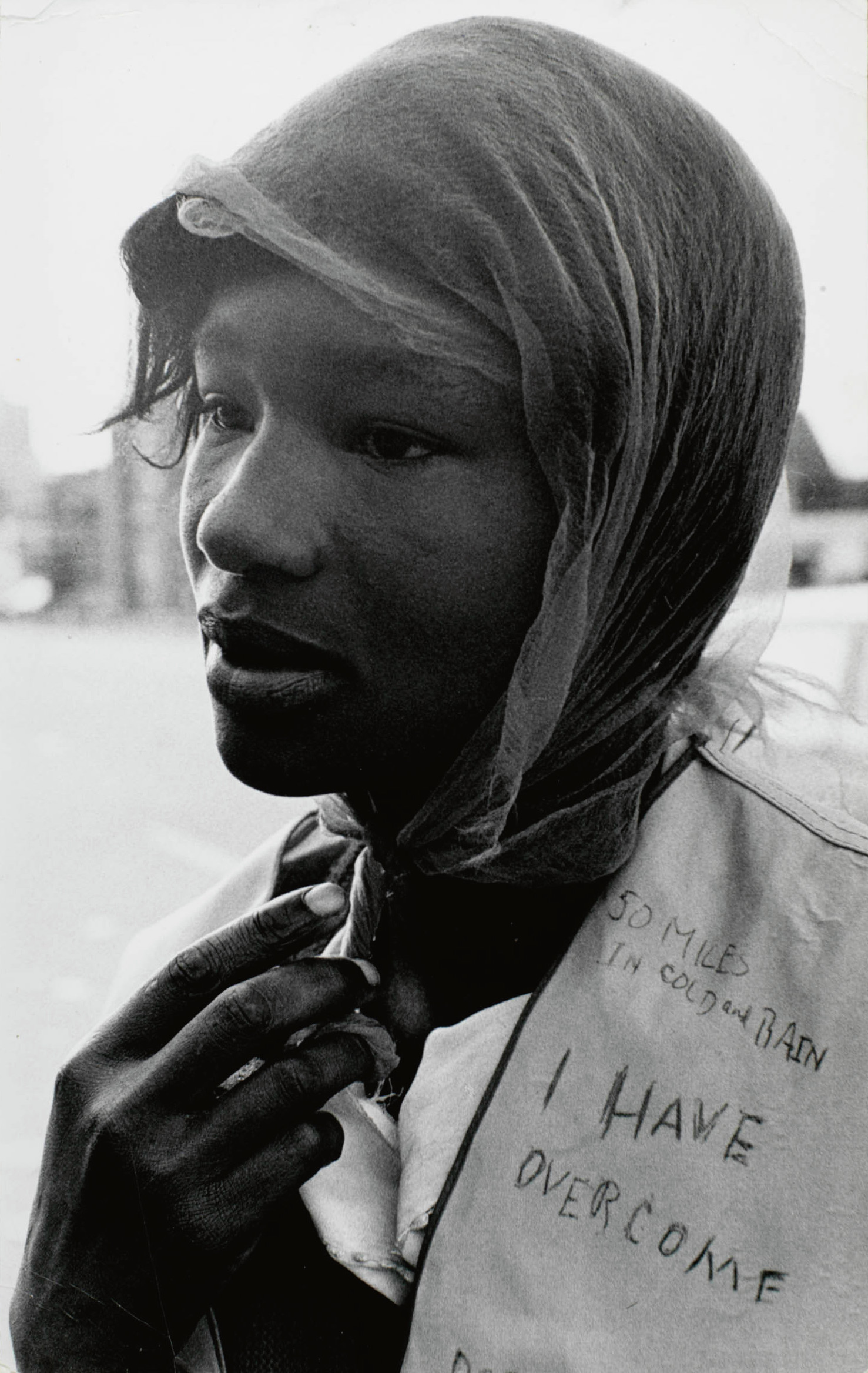

Drawing on the same idea of stylized language on the black activist body as a sign of activity and agency, Ivan Massar’s photograph of Doris Wilson (fig. 2) on the 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama also captures how words written and worn on the black body are signs of political agency. Massar’s photograph of Wilson is a candid and intimate moment that captures her in a moment of dress correction. There is a softness to the photograph evoked by the textural visibility of the sheer headscarf Wilson wears. The wrinkles of the headscarf draw the viewer’s eye toward her fingers which are entwined in the scarf making visible a sense of agency through self-care and maintenance. [10] While black protestors implemented ideas of comportment and respectability in their everyday dress worn in protest, they also found further expression and liberation in how they chose to use signs-as-dress as subversive critiques of the idea that they needed to be like white Americans in presentation. John Oliver Killens, an African American writer and civil rights activist, wrote in an article for The New York Times in 1964, “We are not fighting for the right to be like you. We respect ourselves too much for that. When we fight for freedom, we mean freedom for us to be black, or brown, and you to be white and yet live together in a free and equal society.” [11] Dress practice on the space of the black body is a space of free expression of self, not proof of assimilation into a white dominated society. Along with her headscarf, Wilson wears what looks like a vest covered in handwritten phrases reading, “50 miles in cold and rain…I have overcome….” The words appear scratched into the fabric of her clothing. The letters are not neatly organized, but crudely branded into the stitch-work of her outerwear. There is a visible textural contrast between the softness of her gaze, the material of her headscarf towards which the viewer’s gaze is directed, and the energy of the jagged lines that form words on her vest, which inscribes her body as political—endowing her with a sense of activity and agency.

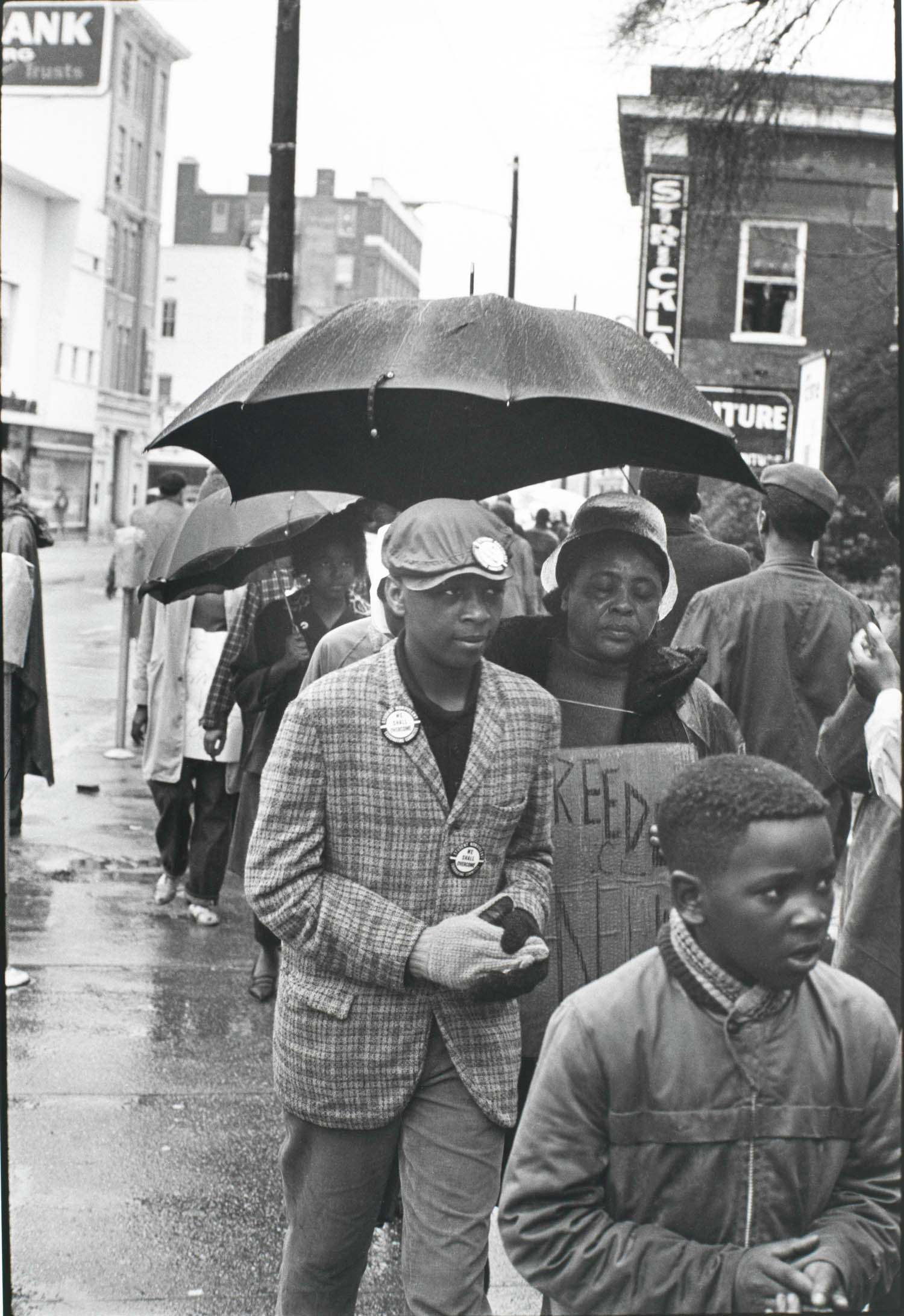

Often, protest dress visibly disrupts the image of the respectably dressed and passively protesting black body. While written signs are one way in which the body is literally re-inscribed with meaning, accessories like political buttons also disrupt the “properly” dressed body to endow it with agency as they confuse positions of what lies externally and more central to the body. In Danny Lyon’s photograph of Fannie Lou Hamer marching in Hattiesburg, Mississippi in 1964 with a group of young boys (fig. 3), the camera’s eye focuses on the young boy who walks with his hands clasped alongside Hamer. He wears a tweed jacket and a newsboy cap. His outfit is accented with political buttons. Wearing one white and one black glove, the boy calls upon familiar visualizations of racial integration and harmony that used imagery of white and black hands joined together (fig. 4). The buttons are not legible from a distance but based on the style they look like SNCC buttons that read, “Support Southern Students” (fig. 5). The buttons occupy a status as an object of history which combats the ephemerality of passing dress trends, further grounding the black body in the context of its own visual history. The buttons subtly disrupt the composition of his dress insofar as they literally puncture the clothes he wears. Placed meticulously on the brim of his cap, his right lapel, and beneath his first button, the political protest dress he wears allows him to critique normalizing activist images of the black body as passive by inserting his own political self-fashioning. [12]

Art That Reaches Out As Well As In

Protest dress collapses the experience of seeing and reading, in that sensory experiences are not understood as independent sensations but rather codependent in the context of the black body. Image and text become situated in the symbolic meaning of the skin as a space of both experiencing and perceiving information. The skin as a surface both alters and makes meaning depending on what comes in contact with it. The American flag was both carried and worn during civil rights protests not only as a reminder of the right of African Americans to complete citizenship, but also as the symbol of hope and the possibility of dreaming of a new existence or way of being in society. To wrap oneself in a flag is to dream openly of a new skin, or rather a new surface and space for understanding and forming the self. Bruce Davidson’s photograph of a young black man wrapped in the American flag during the Selma march in 1965 (fig. 6) not only reinforces how black civil rights activists wanted to see American values realized within society, but also a call to action directed toward the spectator. The boy photographed looks directly into the camera’s eye as his head is angled downward, confronting its gaze. The boy wraps the American flag around his body; however it does not engulf or overpower him. His frontward gaze is a mark of presence, and also enacts what Ariella Azoulay calls the spectatorial contract, or rather one that, “call[s] on [the spectator] to recognize and restore [the photographed individual’s] citizenship through…viewing.” The photographed individual who dares to look back and face the petrifying gaze of the camera is one who demands to be witnessed. The spectator must honor that declaration of presence by affirming his status as a citizen through reading how the new meaning of the flag is conceived on his body. The American flag as dress evokes the space of dream-work and conceiving of a new sense of place. It is a form of protest dress that unabashedly embraces hope and the radical power of self-love and affirmation.

Protest dress offers black activists a greater sense of control over their own public appearance. Civil rights demonstrators were aware that they were being photographed and political dress practice became a way in which black activists could conceive of escaping the threat of history miswriting their story. Quoting James Baldwin, bell hooks writes, “Baldwin wrote that, ‘people are trapped in history and history is trapped in them,’ there is only the fantasy of escape, or the promise that what is lost will be found, rediscovered, and returned.” [14] Protest dress offers the hope that marginalized individuals will escape and free themselves from the totalizing power of history. Protest dress through signage and accessories acts as a performance of both self and citizenship within the public sphere. The photographs of black activists dressed in this manner also show how citizenship is not stable, but as Azoulay writes, “…a struggle to achieve, but an arena of conflict and negotiation.” [15] However, it is in this space of negation amidst struggle where dress practice serves to help fight against disenfranchisement. Just as Lucy Lippard writes of activist art, protest dress, “is an art that reaches out as well as in.” [16]

Notes:

[1] Jacques Rancière defines the freed or emancipated spectator as one who, “challenges the opposition between viewing and acting…when [they] understand that the self-evident facts that structure the relations between saying, seeing and doing belong to the structure of domination and subjection.” The emancipated spectator is needed in order to save the photographed black body from further domination by representation through a critique of dominant images.; Rancière, Jacques. "The Emancipated Spectator, trans." G. Elliott (London and New York: Verso) (2009), 13.

[2] Martin A. Berger attests to the normalization of the myth of black inactivity by stating, “In both public imagination and our history books, the civil rights story is overwhelmingly one of well-behaved black protestors victimized by racist and violent whites.” Berger, Martin A. Freedom Now!: Forgotten Photographs of the Civil Rights Struggle. University of California Press, 2014,9.

[3] For the purpose of this article, Elspeth H. Brown and Thy Phu’s definition of ‘feelings’ as, “aspects of affect to which we have direct, subjective access,” and ‘emotions’ as, “signify[ing] the underlying, physiological phenomena, worked out in the body (e.g. a quickened heart rate, a giddiness in the solar plexus)” will be used.; Brown, Elspeth H., and Thy Phu, eds. Feeling Photography. Duke University Press, 2014, 6.

[4] As Laura Montani, scholar and design consultant, suggests, accessories allow the individual to, “play pretend…[which] leads to the production of ‘narrative constructions’”.Giorcelli, Cristina, Paula Rabinowitz, Laura Montani, and Mariuccia Mandelli. Exchanging Clothes: Habits of Being II. University of Minnesota Press, 2012, 17.

[5] In this sentence, ‘critique’ is being used in the Foucauldian sense of, “… the movement by which the subject gives himself the right to question truth on its effects of power and question power on its discourses of truth.”; Foucault, Michel. "What is Critique." The Politics of Truth (1997): 23-82.

[6] Eicher, Joanne B. and Mary Ellen Roach-Higgins, ‘Definition and Classification of Dress,’ in Ruth Barnes and Joanne B. Eicher, Dress and Gender: Making and Meaning in Cultural Contexts (Oxford: Berg, 1993), pp. 8-28, 8.

[7] Willis, Deborah; “Introduction,” Davidson, Bruce. Time of Change: Civil Rights Photographs 1961-1965, St. Ann’s Press, 2002, i.

[8] Murphey, Murray G. "Signs, Acts, and Objects." Social Science History 11, no. 2 (1987): 211-32. doi:10.2307/1170898, 212.

[9] hooks, bell, “Feminism Inside: Toward a Black Body Politic”, Francina, Francis, ed. Modern Art culture: A Reader. Routledge, 2009, 20.

[10] Susan Leigh Foster writes in regards to early sit-in organized by the Chicago Committee of Racial Equality (CORE), “Practicing non-violence, especially in the face of those who ignored the codes of civility and comportment, [protestors] imposed themselves as proper rather than unruly, a potential object for compassion rather than a figure that inspired fear.”Foster, Susan Leigh. "Choreographies of Protest." Theatre Journal 55, no. 3 (2003): 395-412, 400.

[11] John O. Killens, “Explanation of the ‘Black Psyche,’ The New York Times (Magazine), June 7, 1964, pp.37-42, and 47-48; Meier, August, Elliott M. Rudwick, and Francis L. Broderick, eds. Black Protest Thought in the Twentieth Century. Vol. 56. Bobbs-Merrill, 1971, 426.

[12] Protest accessories perform a nuanced critique of representations of the black body in civil right photographs insofar as the subject, as Foucault might say, “[gives] himself the right to question truth on its effect of power and question power on its discourses of truth” through the agency of dress practice.; Foucault, Michel. "What is Critique." The Politics of Truth (1997): 23-82.

[13] Azoulay, Ariella. The Civil Contract. New York: Zone Books, 2008,31.

[14] hooks, bell. Black looks. 2001, 173.

[15] Azoulay, Ariella. The Civil Contract. New York: Zone Books, 2008,31.

[16] Lippard, Lucy, “Trojan Horse: Activist Art and Power,” Frascina, Francis, ed. Modern art culture: a reader. Routledge, 2009, 196