The Red Shirt

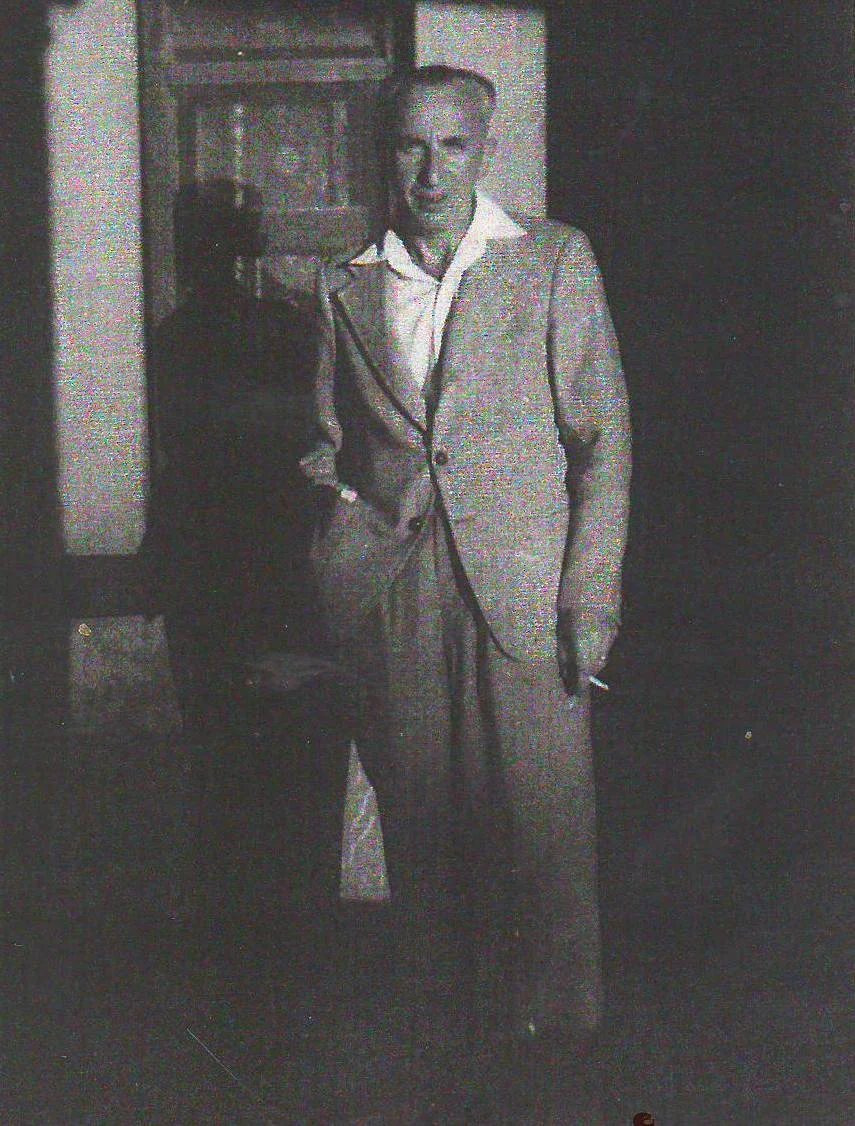

Oupa. Image courtesy the author.

My garment of garments, the one whose memory I still adore about 50 years after I wore it, was a shirt that came from Bloch’s of Koffiefontein, the general dealership belonging to my Oupa (grandfather) Barney Bloch. Koffiefontein was (and still is) a tiny dorp (village), in the landlocked heart of South Africa, that came into being with the diamond rush of the 1870s.

When he was a boy of about 15 , my grandfather, together with his sister Jane, had been sent from his home near Telz in Lithuania, to join their elder brothers, Louis and Israel, in South Africa. He may well never have met these brothers. They owned a shop in a town called Bloemfontein. After Oupa finished school , he worked in this shop before moving to nearby Koffiefontein, the home of my grandmother Jessie. After their arranged and ultimately unhappy marriage, her family, who owned their own successful shop there, helped Barney to open Bloch’s.

At least in outline, this is a familiar history for South Africans of Jewish origin. During the first decades of the 20th Century, Lithuanian Jews were subjected to wave upon wave of brutal pogroms at the hands of the Cossacks. Jewish youths like my grandfather were also faced with a 10-year conscription period in the Russian army. Tens of thousands fled to South Africa, amongst other destinations, and many worked as “smouse” or travelling pedlars, or opened shops.

A few years ago, an elderly cousin of my father’s popped up unexpectedly. He told me that my grandfather had been a natty dresser, who always made a point of wearing a well-cut suit. Though the few old photographs I’d seen confirmed this, it was still hard to imagine. I only knew him in his final decade, when old gents’ cardigans and baggy trousers had become his uniform. I say I knew him, but I never did; I hadn’t been told much about his earlier incarnations. I was aware that my grandmother had at some stage absconded with a man called Max to the town of Germiston. After he and my granny were divorced, Oupa had become a table boarder with a Mrs Appel, but otherwise continued to live and work just as he had before.

As for his character, he kept his thoughts to himself, and when he did speak, it was in a quiet, thickly accented voice. Oupa was probably mild by temperament, but I wonder if his extreme reserve had something to do with the enduring shock of his boyhood emigration. He and his sister were put on a train to Berlin headed for London. From there, they boarded a ship to Cape Town. The family tree records that Barney and Jane were accompanied by an uncle as far as Berlin. They were so frightened of being left alone for the rest of the journey that they begged him to continue with them to London. Whether he did or not isn’t clear. London must surely have seemed overwhelmingly vast and alien to them. I wonder where they stayed there, before their final voyage. It was probably somewhere in the East End. It’s likely that I walked along the same streets as they had on my regular Sunday morning visits to the market at Brick Lane when I lived in Hackney about 75 years after their sojourn there, though I was far too absorbed in the market and its promised spoils to think about this at the time.

“He told me that my grandfather had been a natty dresser, who always made a point of wearing a well-cut suit. ”

My father told me that although Oupa never spoke about his parents or his childhood, he did say that he had found the voyage very difficult. I try to imagine how he and his sister felt as they watched their lives literally fade into an irretrievable distance, to be replaced by something entirely unfamiliar. It’s sad and disheartening that the same questions apply to the often far harsher experiences of so many millions of young people in the subsequent decades of the last century and into our own time.

My beautiful red shirt entered my sartorial orbit in about 1965, on one of our family holidays in Koffiefontein. We travelled there from our coastal hometown of Port Elizabeth, twice or three times in my early childhood. During these visits we spent time at Oupa’s shop as a matter of course. Through the eyes of a tiny child, it was a big, darkish space with high counters bearing glass jars of sweeties, and a pile of pre-cut squares of brown paper. I don’t exactly remember the clothing, only the flash and swish as the hands of friendly but intimidating adults moved hangers briskly along a rail.

My father, who had worked in the shop during his university holidays in the early 1950s, recalled serving both local white farmers and their impoverished black workers, who came in on Saturdays to spend their meagre wages on tiny paper parcels of sugar and other perishables. My father insisted that there was never apartheid in Oupa’s shop. Everyone used the same entrance and was treated the same. This recollection was later confirmed by his cousin, who remembered two entrances, not for the purposes of dividing the customers according to race, but to separate the clothing and the grocery sections.

“ I don’t exactly remember the clothing, only the flash and swish as the hands of friendly but intimidating adults moved hangers briskly along a rail.”

I’m intrigued by another of my father’s memories of the shop. On its sign, beneath the moniker Bloch’s of Koffiefontein rendered in curly cursive was the slogan “From a needle to an anchor.” It was accompanied by a painted image of each extreme. Its promise or perhaps boast was that the shop stocked a range of goods so broad that its customers every need and desire was catered for. Nowadays, even the assumption of such modesty on the part of consumers seems impossibly old-fashioned. In this era of mind-boggling excess and relentless advertising, who would feel entirely satisfied with the merchandise sold by only one shop, even if they lived in Koffiefontein? My father’s memory of a more innocent, less acquisitive time, when enough was enough, underlines the almost unbelievable changes over the past 60 or 70 years in what most consumers get to see and, at least in theory, choose from, and consequently, expect and want.

The author as a child. Image courtesy the author.

As far as my own acquisition of the red shirt goes, there was probably no active choice on my part. I was a very small child at the time, and was given far less leeway to assert my own tastes than children of later generations. I don’t know how I felt when I first tried the shirt on, but presumably, beyond the obvious fact that it was the right size, even at that tender age, there was a good fit between us, the unspoken sense of a partnership in the making, the magical realization that this will work, waiting to be confirmed and reinforced with each successive wearing. The shirt may have been a boy’s shirt with its buttons on the right hand side. As such, it may possibly have been the first unconscious inspiration for my adult choice to wear clothes more or less unfettered by the dictates of gendered fashion. At any time, there are almost as many men’s as women’s shirts hanging in my wardrobe. I try to follow a middle path, of sorts in this regard. I won’t countenance frills or excess girly details, but equally, I try no longer to be seduced by a fabulous pattern on a man’s shirt to the point that I overlook the indefensible crime of a stiff, uncomfortable man collar.

More important than my favorite shirt’s style, though, was its color. It was made from some newly invented, very warm, synthetic fabric that allowed for an overpowering, luminous glow. The glorious blaze of its redness may well have ignited my lifelong love affair with color, and more, with the pleasures of sight and seeing. For me, as it turned out, this was a precious and tenuous blessing, rather than simply a part of my birthright as a human. I lost the sight in my right eye when I was 16, and over the course of the last six years, have had no choice but to accept a dramatic and disabling decline in my left.

With this more recent and more profound impairment, my world has become both unmanageably bright as well as weirdly green, but I can still see red well. I’ve always enjoyed wearing or carrying a touch of red - a watch strap once, a Lee jacket for a while, my toweling bathrobe, and several handbags. As I’ve grown older, I’ve noticed the tendency to wish to replace those clothes and accessories that have stood out as my very favorites with more of the same, or at least with reminders or simulations. When my red bag was stolen in a smash and grab incident at the perilous Harrow Road traffic lights in Johannesburg in about 2004, I made haste to return to the shop I had bought it at, and was overjoyed, even relieved, to find they still had one of the same models in stock. My current red bag, hand-made by a Cameroonian rastaman called Ndir, is also a replacement for another precious stolen predecessor. It’s far cruder and chunkier, a lot less elegant than its antecedent, which came from a market at Cannobio on the pristine banks of Lake Maggiore, rather than the windswept sandy one up the road at Muizenburg, on the edge of the Indian Ocean. But who cares? It’s much admired.

As for shirts, after that first marvelous founding exemplar, I can’t remember wearing any others for many years. I bought my first adult red shirt about 15 years ago, during a season when shirts were made annoyingly short. That defect aside, it was perfect. It was made of soft baby cord and sported shiny silver stud buttons, and I wore it more or less to death. After that, though, there was another prolonged absence on the red shirt front. Maybe I was thinking of my long lost darling when I bought a piece of scarlet fabric with a white floral pattern on it five years ago. I had it made into a shirt at Miss Prissy’s, a tailors shop in nearby Wynberg presided over by the charming Ms P, whose speciality is clothing made up from fabric bought in Tanzania and other countries to the north of South Africa. The shirt she produced for me, with its soft, comfortable brushed feel, is a great success, but disqualified as a true descendant, replacement, or even memorial, by its flowery pattern.

“The glorious blaze of its redness may well have ignited my lifelong love affair with color, and more, with the pleasures of sight and seeing. ”

So the hunt continued. It was made slower and more complicated by a growing desire to wear as much second-hand clothing as possible, as well as the difficulty of being dependent on the assistance of a shopping companion with both better sight than my own and a good feel for my sartorial taste. But very luckily, such a person does exist; and if visual impairment teaches one anything, it teaches one patience. A year or so ago, at the tiny fortnightly market up the road where we’ve had wonderful success in finding interesting clothing, another red shirt at last appeared... it’s only been pinned, so far, and still needs to be altered permanently, but it shows every sign of nascent excellence.

The sole photograph I have of myself wearing its iconic first small ancestor was taken at the Mac Mac Falls in the then Eastern Transvaal. The focus is the waterfall, really; but there I am, squashed into the bottom right corner, wearing a rather fetching pair of silver-framed glasses, and of course, my favorite shirt, which imparts a vivid splash of color to the image. I remember managing only a hint of the obligatory smile. I had a terrible stomach ache, as I often seemed to in my early childhood, and had been sobbing my way along the dirt path leading to the Falls viewing point. Maybe those tears account for my very rosy cheeks in the picture – or is it just the super-potent reflection of my most beloved shirt?