From the Altar to the Runway: Fashioning the Roman Catholic Priest

Print advertisements and runway shows promoting Italian fashion duo Domenico Dolce and Stefano Gabbana’s Men’s Fall/Winter 2014 campaign, “Devotion,” were manned by young Sicilians in garments inspired by the black street-wear and polychromatic liturgical vestments of acolytes, seminarians, and priests. In the campaign’s advertisements, the fashion duo arranged men and women in a mix of playful and solemn poses within the stone courtyards of a convent or monastery. In one particularly striking image, a priest or seminarian dressed in a black cassock is surrounded by other men—presumably representing other seminarians or priests, too—who sport jackets embroidered with trendy floral motifs.

The black cassock of the central male figure—handsome and brooding—faithfully reproduces the clerical garb still in use by men of the cloth today, and the other men’s floral embroidery in shades of red, gold, green, and blue calls to mind the liturgical vestments or garments worn by priests at the celebration of the Catholic mass like the chasuble and the pluvial cope. The accessory presence of a woman interrupts the otherwise homosocial scene, which conjures the male-dominated hierarchy of the Catholic Church. The advertisement tells an ambiguous story, leaving any interpretation to the imagination of the viewer. At the very least, “Devotion” draws attention to the fact that the Catholic priest and the mysterious world he inhabits continue to fuel the imaginations of couturiers and their consumers, while simultaneously making visible the affinities and seams between fashion and religion.

Since the European Middle Ages, religious dress and ornamentation have gone hand-in-hand with the lush fabrics and craftsmanship now associated with haute couture. [1] As the name chosen for Dolce and Gabbana’s 2014 fall/winter campaign signals, fashion itself has always been a matter of an almost religious devotion to sartorial art and beauty, with figures like Yves Saint-Laurent and Karl Lagerfeld as its high priests. [2] Curiously, the most opulent liturgical vestments were and still are created to adorn the celibate male body exclusively, at least within Catholicism. [3] While the dress of nuns and other religious women communicates notions of abnegation, humility and modesty, men of the cloth (priests, bishops, cardinals, popes) have throughout history adorned themselves in an array of ornate garments that serve to solidify the power and wealth—not to mention the kingdom and the glory—of the Catholic Church. If the pedestrian black cassock or slacks are meant to mark priests as humble servants to God and their parishioners, besides serving a purpose as practical daily wear, liturgical vestments—including a dizzying array of ornamental robes and accessories with arcane names like chasubles, pluvial copes, miters, and stoles—invest the clerical wearer with spiritual as well as socioeconomic and political power. When a bishop or cardinal says mass in his resplendent apparel, the resulting tableau of gold thread and polychromatic silk brocade is meant to heighten Catholic rituals while ennobling the priest as a bridge between the human and the divine. [4]

From the young seminarians in Dolce & Gabbana’s “Devotion” to the impeccable papal insignia of Jude Law’s Vatican in The Young Pope and the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s recent “Heavenly Bodies” exhibition, contemporary fashion designers and filmmakers (not to mention their consumer audiences) have embraced the wholesale eroticization and spectacularization of the celibate male body and his contradictorily austere and extravagant wardrobe. In this essay, I briefly historicize and contextualize these and other cultural products while teasing out the ways the religious male body has been utilized to communicate broader attitudes and contradictions inherent in masculine self-presentation today. I focus especially on some of the press coverage of the papacies of Benedict XVI and Francis I, as well as scenes from Federico Fellini’s Roma (1972) and Paolo Sorrentino’s limited HBO series The Young Pope (2017). On the one hand, the simple, clerical everyday-wear of priests symbolizes the sublimation of the male body and the desiring individual, a remnant of the monastic rule prevalent during the Middle Ages and beyond. On the other hand, liturgical vestments draw attention to the priest’s body as a site for awe-inspiring and spectacular self-display in order to match the sacred mysteries of Catholic rites and sacraments. Despite the apparent contradiction between these two modes of self-presentation that commingle in the figure of the priest, artists affectively capitalize on both configurations. In so doing, designers and filmmakers identify the priest as a historically significant male archetype that informs as much as it reflects and resists shifting attitudes towards and ideals of masculinity.

Clerical Fashion, Clerical Masculinity

The origins of most ecclesiastical apparel can be traced to the everyday clothing available to patrician men of the Roman Empire. These items of dress, such as the chasuble—a poncho-like covering derived from the paenula of ancient Romans—were usually made of simple, inexpensive fabrics like linen or wool and were devoid of decorative elements. Initially, no distinction was made between the sartorial habits of ancient Christian clergymen and their parishioners. Over time, and as secular fashions evolved, clerical sartorial patterns remained the same and thus today represent a kind of fossilized fashion; design elements reflect generational shifts in aesthetic tastes, but the silhouettes of such garments have gone mostly unchanged since the Middle Ages.

The humility of the priest’s original vestments is a distant memory when compared to the current sartorial rubrics available to the members of the Roman Catholic Church’s pyramidal hierarchy. Even in the current sartorial paradigms, priests, bishops, cardinals, and the pope continue to adorn themselves in expensive satins and silks. Catalogues of clerical fashions—you, too, can have a bespoke processional cope of your own!—report that even the “simplest” of chasubles fetch costs in the hundreds and thousands, depending of course on the intricacy of the design and the quality of fabric utilized.

A priest’s clerical street-wear—cassocks or the more common shirt and slacks—is not as eye-catching as liturgical vestments for the simplicity of its silhouette and black or monochromatic color palette. [5] The soutane, more commonly known as a cassock in English, derives from the Latin subtus or beneath, an allusion to its being worn underneath ceremonial or liturgical vestments during the priest’s vesting in the sacristy. The cut of the soutane derives from similar dress once worn by medieval academics and has always been visually austere, even if the fabrics themselves can be posh; the processes used to make one are also notoriously complex. [6] In the present day the cassock is only de rigueur for high-ranking prelates, but it is still used by seminarians and traditionalists. The cassock provides contemporary clerics with an opportunity to distinguish themselves from the more liberally-minded among them, or from those who lived through the modernizing reforms that resulted from the Second Vatican Council or Vatican II (1962-1965). In Sorrentino’s The Young Pope, Cardinal Spencer (James Cromwell), the aging and begrudged mentor of Lenny Belardo (Jude Law), at one point exclaims that “the young are always more conservative than the old,” foreshadowing his mentee’s retrograde aesthetic and ethical modus operandi that shocks the rest of the show’s characters.

I have been writing about priests, fashion, and masculinity for some time now, but I understand how “clerical masculinity” may at least initially sound as oxymoronic as “clerical fashion.” In other words, the clerical descriptor could seem to contradict the more fluid categories it purportedly qualifies. Fashion is, after all, in a perpetual state of flux from season to season. Masculinity—or that which is deemed masculine or manly—is a social category that varies widely according to time, place, and other factors such as socioeconomic status, race, and age. However, the gender of priests is hardly inconsequential or detached from broader notions of masculinity, as Derek Neal poignantly remarks, since a Catholic cleric’s identity still depends on his being male. [7] With gender and sexuality forming separate elements of a person’s identity, a priest’s celibacy does not preclude him from discussions of masculinity writ large, particularly since patterns of masculinity have, historically, been associated with characteristics and values that have little to do with an obvious or even overt sexuality.

“With gender and sexuality forming separate elements of a person’s identity, a priest’s celibacy does not preclude him from discussions of masculinity writ large.”

Such historically masculine behaviors and traits in the West trace their roots to the ancient Roman concept of virilitas and include discreet or modest self-presentation, self-control or an “ethic of moderation,” accomplishment, and even political engagement. [8] In the vocabulary of clothing and fashion, these attributes are enshrined in the black or neutral suit, which became the symbol for masculine power and advancement throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Clerical dress—and liturgical ornaments in particular—allow artists, designers, and storytellers to give whimsical contour to masculine power in their sartorial narratives. Literary critic Herbert Sussman, for example, has convincingly demonstrated that the nineteenth-century image of priests and monks struggling with sexual temptation was part of a common symbolic repertoire deployed by late Victorian authors to allegorize broader cultural and medical writings about masculinity that recommended that middle-class men refrain from indulging in too much sex. Among other negative effects of engaging in too much sexual activity, the loss of seminal fluids was popularly thought to deplete men of their vitality, and so its careful distribution was vital to nineteenth-century ideals of masculinity.

All of this is to say that the imagined struggles of the celibate priest, commonly depicted in art, film, literature, and even fashion campaigns as the Dolce & Gabbana example illustrates, function as rich icons that have the unique ability to gloss historical and constantly shifting attitudes of masculine self-presentation: from the exaggerated austerity of the black or monochromatic cassock to the peacock-like opulence and magnificence of flowing, liturgical robes.

A show like The Young Pope, for example, overturns masculine conventions, given Lenny’s (Jude Law’s) wholesale embrace of sartorial finery as a symbol of abiding masculine-coded power.

Papal Fashion Today: Benedict XVI and Francis I

Press coverage of recent papacies serves as a prime example of the visibility given to these topics today, while demonstrating how the pope represents an especially potent example of the crossover between secular, mainstream conversations about masculinity and fashion, and those thought to be more esoteric. During the relatively short-lived papacy of Benedict XVI (2005-2013), newspapers and magazines exploded with rumors that the pontiff’s shoes were made by luxury fashion label Prada—they were not, of course, but this did not stop international news outlets, from Spanish daily newspaper El Mundo to American men’s review GQ, from capitalizing—not without a touch of irony—on the moment in their treatment of the figure as an enigmatic and unexpected sartorial icon. The cobbler turned out to be Roman craftsman Adriano Steffanelli, who has also made shoes for Pope John Paul II and other heads of state. The red shoes were only one among a handful of archaic items of dress resurrected by the first German pontiff. Another included the velvet mozzetta—a short, shoulder-length cape lined with white ermine—which recalls aristocratic outfits of the medieval and renaissance periods, thus further distancing Ratzinger from his immediate predecessors.

On the other end of the papal-sartorial spectrum, current Pope Francis I’s austerity has become a trope of journal and magazine publications for his restrained aesthetic of austere simplicity. The Argentine Jesuit has consistently advocated for a shift in attitudes vis-à-vis the aesthetics of the papal office, in line with the “modernizing” spirit of Vatican II. This point of view is at odds with that of the previous pope, Benedict XVI, and his traditionalist stance on sartorial matters. Acknowledging the perspectival shifts in papal dress from Benedict XVI to Francis I, Sally Dwyer-McNulty explains that the recent popes maintain interest in conveying meaning through the careful display of clothing, even if Francis I insists on an image based on an aesthetic of monochromatic austerity and simplicity: “Pope Benedict XVI and Pope Francis agree that the pope holds a position of unique authority, but all the attention to their different styles of dress indicates that these men differ on how that authority should be conveyed through dress.”[9]

Like his predecessor, Francis I was also identified by the men’s style magazines as a fashion icon. In 2013, Esquire magazine chose Francis I as their best dressed man of the year for the monochromatic sobriety of his daily wardrobe: “the opulent jewelry and fur-lined capes of yore have given way to humbler dress, and this break from aesthetic tradition says a lot of the man and what he hopes to achieve while doing his earthly duties.” [10] At least one point to be extracted from these examples is that it is perhaps because of—not despite—the defamiliarizing wardrobe that priests of all ranks are recognizable as sartorial icons whose behavioral and sartorial habits, while serving immediately to distance them from their lay counterparts, nowadays continue as ever to bring them into dialogue with secular patterns of masculinity that are also in a state of flux. While this cross-pollination is immediately apparent in the Dolce & Gabbana advertisement discussed above, filmmakers, too, deploy the lush aesthetic worlds of the priest to project their attachments to this contradictory world, while at the same time glossing fantasies of masculinity that delight in the extravagant clerical styles of the past in performative ways.

From the Sacristy to the Screen: Roma and The Young Pope

The historical weight of ecclesiastical garments on the bodies of priests and popes has been creatively interpreted in a number of films and television shows in recent decades. Fellini’s kaleidoscopic Roma (1972), for example, provides viewers with a sartorial tour de force near the film’s conclusion. In its celebration of the splendors of ancient and modern Rome, Fellini includes what can be described most succinctly as a clerical fashion show: a paradoxical scene that is at once parodic and whimsical, critical but celebratory. Partially censored before the film was released, the fashion show demonstrates particularly well the cultural and physical weight of Roman Catholic aesthetics on modern European filmmakers from historically Catholic nations such as Italy and Spain. The scene also makes visible the paradoxes inherent in a religion that values the humility of the understated styles of country priests and the more garish ones worn by high-ranking Church officials.

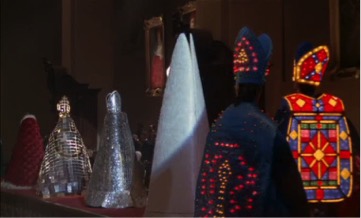

In the scene we see country preachers, a small number of female religious figures, sacristans, and cardinals strolling down the runway, showing off historical designs and trends in religious dress. As the fashion show progresses, the garments are increasingly abstracted and all-encompassing, swallowing the models beneath. The first four figures in the following still image—automatons in chasubles and pluvial copes—move robotically down the runway, followed by men in neon-lit miters and chasubles that recall the stained glass windows of churches and cathedrals.

Despite the campy solemnity of the scene, I find it compelling in the context of this essay for several reasons. First, the scene’s length matches its garishness, finishing after about ten minutes. The show extravagantly highlights the display of clerical daily-wear and liturgical garments, delighting in—even as it mocks—the historically rich material world of the Catholic clergy, heightened by the film’s Roman backdrop. Second, the garments that already eclipse the bodies eventually replace them entirely - it seems that clothes do make the man here, even for priests. The scene ingeniously conflates the Catholic Church’s culture of fashion with the fashion industry’s own religious devotion to sartorialism. The end result illustrates the glorious if slightly bombastic style of liturgical dress. While the bulk of the audience is constituted by other members of the clergy, the presence of Italian statesmen and socialites pinpoints a major component of Italian theorist Giorgio Agamben’s interpretation of liturgical pomp: namely that political power requires a ceremonial or liturgical apparatus to legitimate and sacralize its otherwise secular authority and power.

In a more recent example, HBO’s The Young Pope has provoked a number of essays whose authors describe the show variously as “beautiful and ridiculous,” “beautiful to look at, but as ephemeral and menacing as smoke,” and perhaps most amusingly, as warranting its own H&M clothing line: “The Young Pope’s androgynous line would come with cream-colored sweatsuits—maybe even velour—embroidered with gold. Chains that hang low, dangling at your belly. Big floppy hats. Decadent crystal-adorned kaftans. Stupidly extravagant cheap gold accessories.” [11] The proposal is perhaps not as laughable as it at first sounds, particularly when read alongside the similarly oriented aesthetic of Dolce & Gabbana’s “Devotion”. Attention to the show’s sartorial component is to be expected, given the virtuosity with which costume designer Carlo Poggioli and writer-director Paolo Sorrentino were able to reproduce and stylize their papal mise-en-scène: from the heavily embroidered liturgical robes to the papal tiara. Pius XIII—Jude Law’s papal nom de guerre—also delights in the wealth of the Church he inherits upon his coronation. Pius XIII, the first American pope, strives to recreate ancient formations of masculinity that relied on the immediate recognition of sartorial signs that once—and perhaps still do—communicate male authority and power.

“It’s like wearing six carpets on top of you,” Jude Law jokingly reveals in an interview with Stephen Colbert, surmising that the wizened gait of elderly popes is not a result of age, but rather is due to the burdensome weight of the papal regalia. With that being said, the often-eroticized body of Jude Law in the recent HBO series shimmers in sensuous and extravagant fabrics and ornaments inspired by lush medieval fantasies of pontiffs bedecked in gold and silver tiaras and richly embroidered capes. Even if Lenny’s retrograde aesthetic makes him something like an iconoclast of the modernizing reforms of Vatican II, his character’s almost whimsical display of power resides in his gothic sartorial regime. Jude Law may jokingly complain about the weight of the garments and crown he was often forced to bear, and yet it does not show in Lenny Belardo, who confidently struts around the Vatican in full papal insignia—tiara and pluvial copes in rich greens and reds—typically reserved for use at high mass.

In one memorable scene in Episode 6, Pius XIII is delivered to the Sistine Chapel atop a sedan chair hauled by a retinue of scarlet-clad assistants. Pius XIII wears an ample, red pluvial cope, along with the silver and gold tiara recently brought back to the Vatican from Washington. [12] The horror vacui or fear of blank spaces in the scene is compounded by the crowded room of cardinals, and the impeccably assembled mise-en-scène that reproduces every nook and cranny of the Sistine Chapel. Here as elsewhere in the series, Pius XIII is a far cry from the more muted aesthetic of the current pope, recalling through his ornate apparel and signature red shoes the papacy of Benedict XVI. This is an irony built into Sorrentino’s Vatican, since Lenny Belardo is the first American pope, and thus, as the pilot of the series suggests, is expected by all to be more of a liberal reformer interested in shaking things up in St. Peter’s Square. Though he does shake things up, it is done in the interest of striking fear and awe into global Catholics. Lenny’s American background, in particular, heightens the performative element of his wardrobe. Like the show’s spectators, Lenny is able to embrace the performative splendor one is expected to encounter in a Cecil B. DeMille costume drama. [13]

Conclusion

Though perhaps traditionally viewed as a one-dimensional and immobile symbol of sorts—or as a steward of celibacy and tradition—the Catholic priest is not as static a sign as might be suggested when analyzing the intersecting topics of dress, fashion, and religion, particularly as they intersect with social and political categories of gender and power. The task of reevaluating historical representations of clerical masculinity and ecclesiastical fashion is an important one, given that the priest and the world he inhabits continue to sell, captivating imaginations and inspiring new, eye-catching displays that broadcast extremes of masculinity that oscillate between austere rules of self-presentation and extravagant, peacock-like performance.

The 2018 Costume Institute Gala at New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art (centered on the exhibition theme Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination) further showcased the sartorial confections of designers who have transubstantiated the contradictorily humble and extravagant realities of the sacristy and the altar for spectacular display on the catwalks of Paris and New York. Fictional priests like those found in modern fashion campaigns or the whimsical cinematic fantasies of directors like Fellini and Sorrentino both contribute to and resist the governing myths of masculine normativity, allowing artists and consumers to imaginatively explore alternative fantasies of gender and power.

Notes

[1] Pauline Johnstone, High Fashion in the Church (Leeds: Maney, 2002).

[2] As if Lagerfeld’s signature black suit and stiff white collar were not enough, he was recently the subject of a mini biopic titled Mode als religion (“Fashion as Religion”).

[3] Lynn Hume, The Religious Life of Dress. Global Fashion and Faith (Bloomsbury, 2013), 15.

[4] Patricia Calefato, Luxury: Fashion, Lifestyle and Excess, translated by Lisa Adams (London: Bloomsburg, 2014), 19. Even the less ornate styles used by priests today are crafted with shimmering fabrics and colors meant to interact dynamically with the various types of lighting found in churches and cathedrals.

[5] Higher ranking clerics such as cardinals and the pope wear red and white cassocks, respectively.

[6] Hume, High Fashion in the Church, 8.

[7] Derek Neal, “What Can Historians Do with Clerical Masculinity?,” Negotiating Clerical Identities: Priests, Monks and Masculinity In the Middle Ages, edited by Jennifer Thibodeaux (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 19.

[8] Joshua Rothman, “When Men Wanted to Be Virile,” The New Yorker, Accessed January 12, 2017, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/when-men-wanted-to-be-virile

[9] Sally Dwyer-McNulty, Common Threads. A Cultural History of Clothing in American Catholicism (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2014), 8.

[10] Max Berlinger, “The Best Dressed Man of 2013: Pope Francis,” Esquire, Accessed January 12, 2018, http://www.esquire.com/style/mens-fashion/a26527/pope-francis-style-2013/

[11] James Poniewozik, “Review: The Young Pope is Beautiful and Ridiculous,” The New York Times, Accessed 12 January 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/12/arts/television/review-the-young-pope-is-beautiful-and-ridiculous.html; Rachel Syme, “A Man without Qualities,” The New Yorker, Accessed January 12, 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/a-man-without-qualities-hbos-the-young-pope; and Clover Hope, “The Young Pope Should Do an H&M Line,” Jezebel, Accessed January 12, 2018, https://themuse.jezebel.com/the-young-pope-should-do-an-h-m-line-1791919686

[12] Pope Paul VI auctioned the tiara and donated the proceeds to the poor, which symbolically acknowledged the modernizing reforms of Vatican II that sought to do away with some of the medieval connotations of Catholic rites and sacraments.

[13] Tad Friend, “The Spectacle of ‘The Young Pope,’” The New Yorker, Accessed January 12, 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/01/23/the-spectacle-of-the-young-pope