The Unpublished Musings of Elizabeth Hawes

A hand-scrawled note reads: “Now that Fashion’s Gone to Hell And Dress has become neuter.” [1] The phrase floats alone in the center of a small note page—the type of thing one might expect to find today, coffee-stained and abandoned amid a mess of stir sticks and sugar crystals on a vacant table at Starbucks. A rumination on the state of contemporary fashion jotted down by a writer working through a caffeine fix, perhaps?

It’s a likely find in today’s day and age, except this particular note dates to a very pre-Frappuccino® era, written sometime around 1969 by the resident of apartment #429 of the famed bastion of New York bohemian culture, the Hotel Chelsea. [2] It was written by the one-and-only Elizabeth Hawes.

This name may bring a smile to the face of the reader who is already familiar with Hawes: one of the first American fashion designers to achieve a modicum of celebrity, and the author of the 1938 best-seller Fashion Is Spinach, in which she takes the fashion industry to task with acerbic candor, questioning the supremacy of Paris haute couture and advocating for comfort and functionality in all clothing, regardless of price point. Lesser known are Hawes’ eight other books, written over the next sixteen years on the subjects of not only fashion and beauty, but also gender, labor, and race relations. After receiving her economics degree from Vassar in 1925, Hawes moved to Paris to learn the art of couture, her own version of which she purveyed from her custom salon in New York City from 1928 until 1940, when—concerned with the war looming on horizons ever-nearing —she closed her exclusive operations. [3] [4] Subsequently, Hawes involved herself in social welfare work related to the war, and in an effort to fully understand the plight of the working American woman, she took a job grinding hardware in a New Jersey aeronautics plant. [5] Her experiences as a blue-collar worker are documented in her fifth book, Why Women Cry: or Wenches with Wrenches, as is her resultant career as a labor union organizer.

Throughout all of Hawes’ professional peregrinations, writing remained at the core. Her books are only a fraction of her literary output; her byline was found regularly in McCall’s, Ladies’ Home Journal, Reader’s Digest, Woman’s Home Companion, the Detroit Free Press, and the short-lived liberal newspaper PM. [6] From their pages, Hawes’ iconoclastic views on necessary social reform beat like a lifeline to progress.

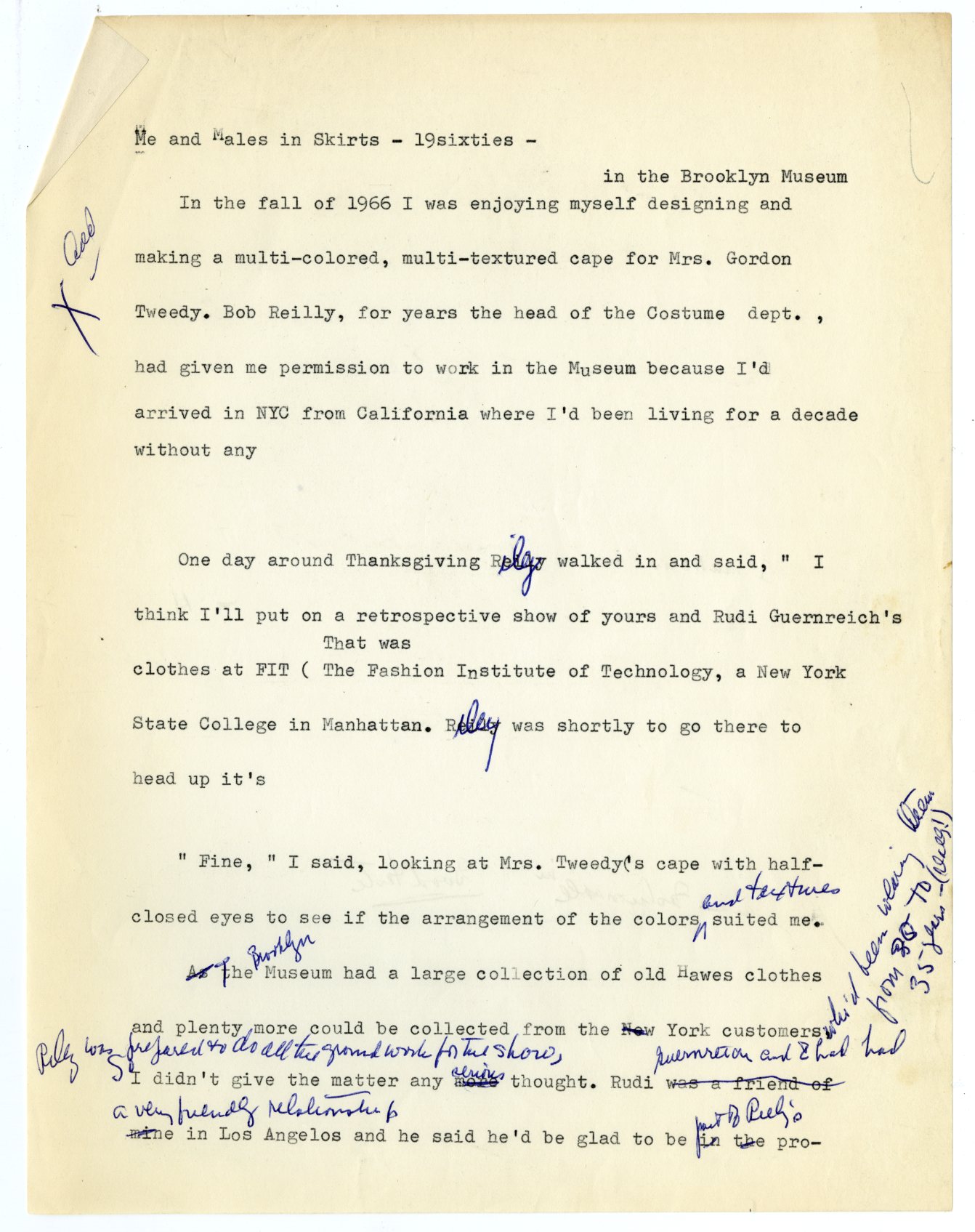

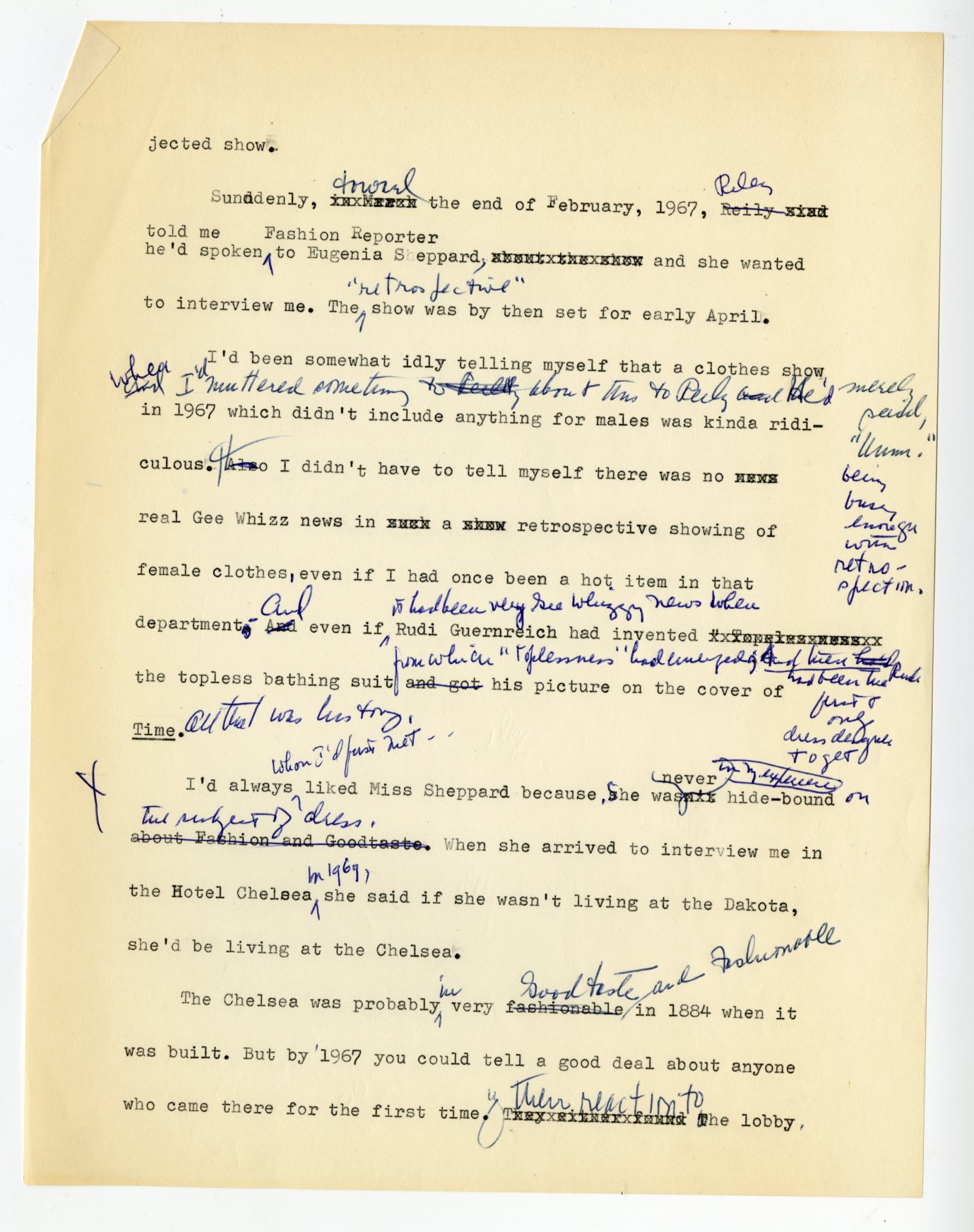

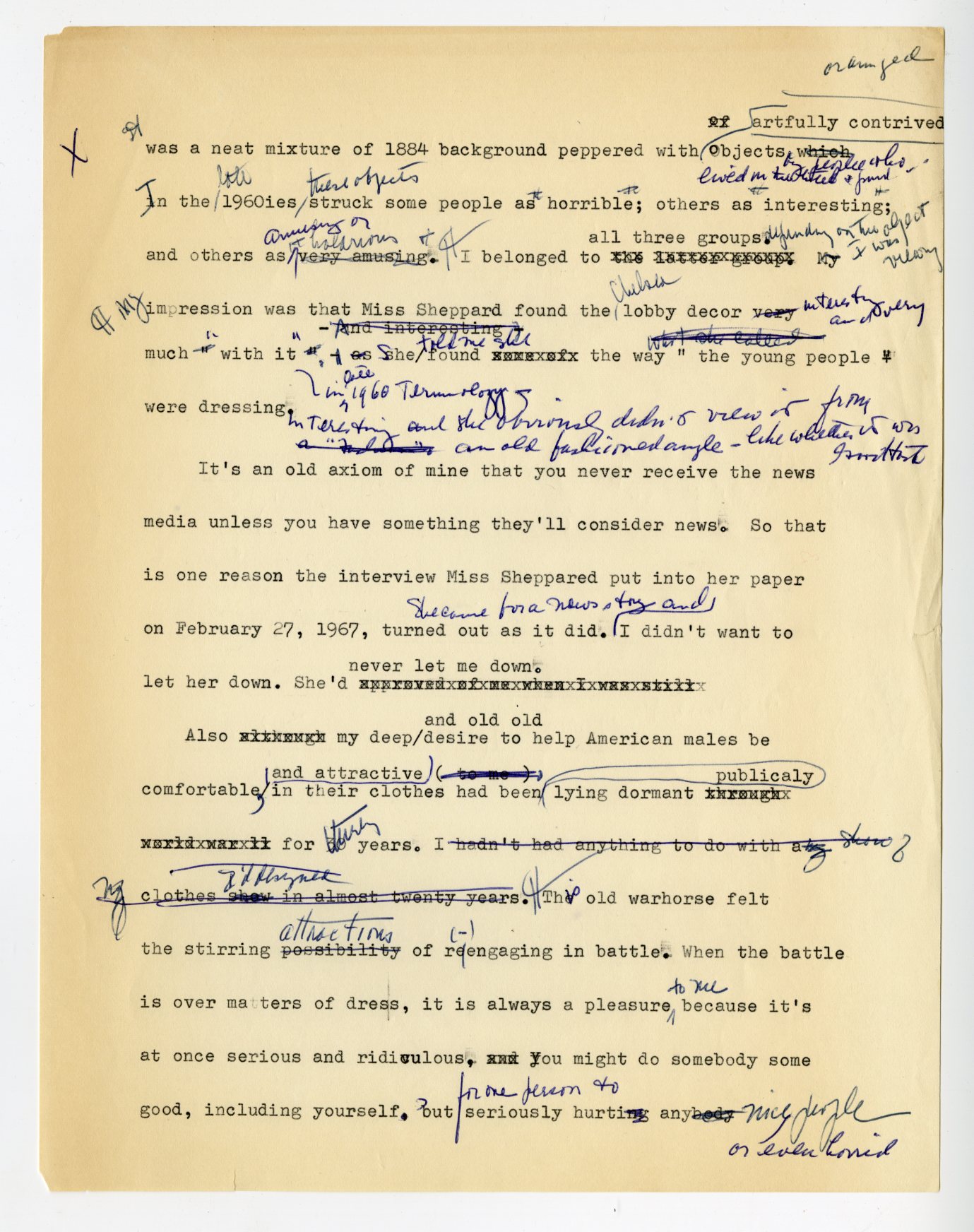

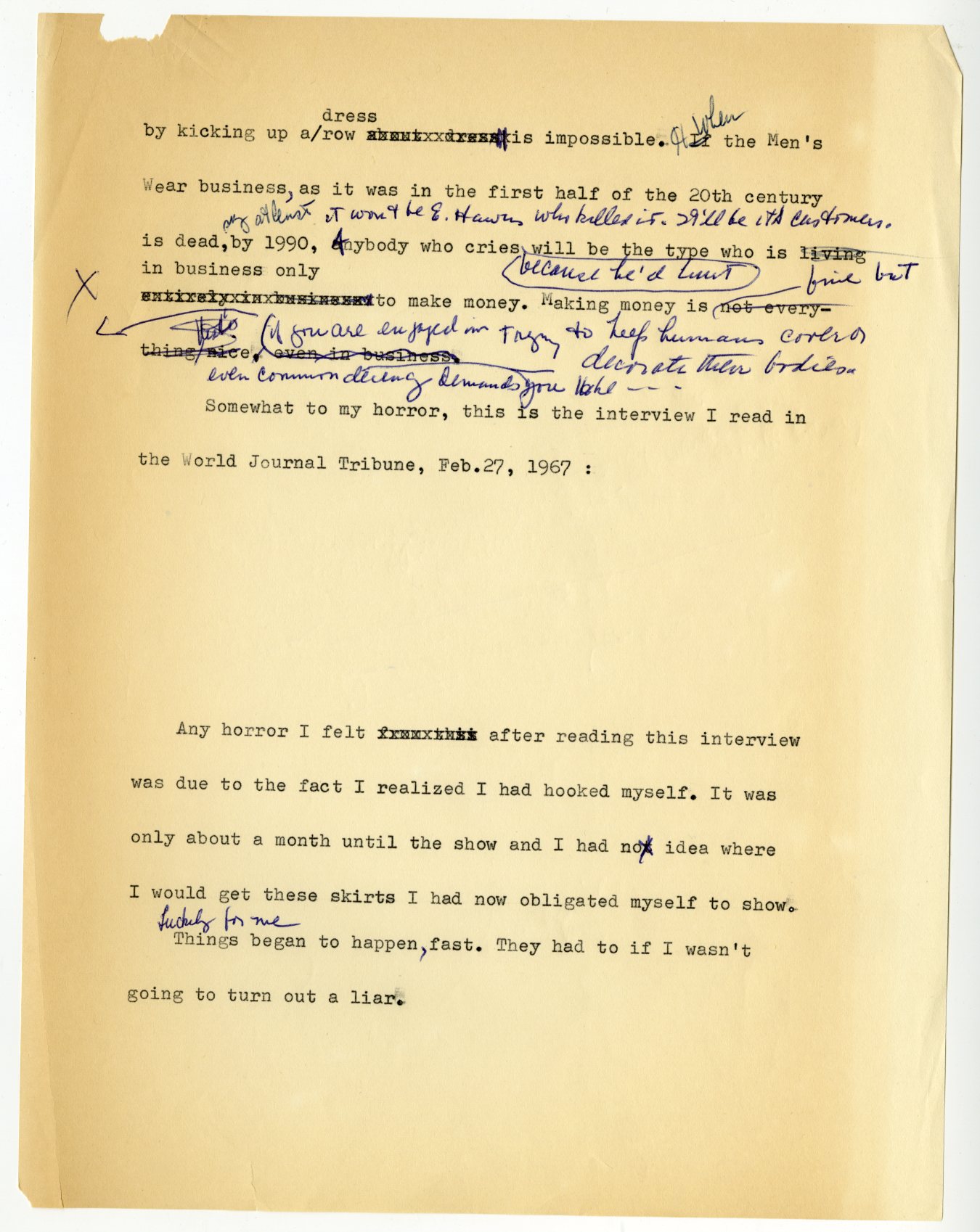

“I don’t mean to set myself up as a witch, although if you enjoy witches, as I do, think of me that way,” writes Hawes in a draft for an unpublished manuscript held by FIT Special Collections and College Archive in the Fashion Institute of Technology’s Gladys Marcus Library. [7] Although not large, the collection of Hawes’ unpublished musings are a rich window into her thoughts on the (r)evolution of fashion up to the early seventies. [8] Examination of the collection as a whole reveals Hawes’ singular preoccupation with gender distinctions in dress, and her futuristic predictions for their eradication. Anecdotes revealed for the first time detail her own early— and sometimes humorous—adoption of pants:

In 1930 I went to France for my summer vacation, mentally prepared for a bicycle trip with Ralph Jester a Yale grad, class of 1925, I’d known him int9mately [sic] but not very thoroughly when I lived in Paris where he was studying sculpture. When I decided to be physically prepared for bicycling by getting some trousers, Mr. Jester acquiesced calmly. I got a fine pair of French workman’s blue jeans. We bicycled around the south of France and almost the entire population who saw me made some amusing comment about the first female they’d ever seen in outer pants. Maybe it was the first time in Western history that anyone shouted, “Is it a boy or a girl?”

The day after some bright eyed young male townies did that. I rode past them and Mr. Jester asked me to stop by some tall bushes on the roadside as we approached a town. He told me, firmly, that I should take off my pants and put on a skirt. I laughed, to myself, and obeyed because I wasn’t brought up to bicker within the family, and I had extended this mannerly behavior to my friends.

I married Mr. Jester about a year later and the marriage lasted only two and a half years. There were a lot of reasons but I’d say that no female who likes to wear trousers should ever marry a male who is really against it. However at the time I married Mr. Jester, I certainly hadn’t taken to trying to figure out my behavior mentally. I proceeded entirely by instinct. [9]

In the seven intervening years before her second marriage, it seems Hawes had wrestled those instincts into submission. [10] Her new husband did not challenge his bride’s choice of attire for their wedding:

I wore blue jeans for my marriage to Mr. Losey. We went over the Vermont border to a small New York state town because in Vermont I couldn’t be married having been divorced. The Justice of the Peace there asked Mr. Losey, “Do you take this man to be your wife?”

From the befogged look on the Justice’s face from the time he saw this female in blue jeans, I’m not sure he said that on purpose. But maybe. Who ever heard of a female being married in trousers—in 1937? [11]

Hawes’ staunch feminism was part and parcel to her rational humanism; her beliefs on the gendering of silhouettes flowed both ways: “Actually by 1967 there was no men’s clothing left in the United States. American females began quietly taking it during the 1950s. Nobody made any real effort to stop them.” [12] Hawes continues on, lamenting the American male’s perceived lack of sartorial freedom: “At the same time, American men chose to continue to believe that there were still women’s clothes which no man could wear.” [13]

Hawes first introduced the notion of skirts for men in 1938 by titling one of the chapters in Fashion is Spinach, “Men Might Like Skirts.” [14] Far from being a literal suggestion, the provocative title was used to tease out the chapter’s theme: why do men continue to wear clothing they find uncomfortable? It would be another three decades before Hawes mobilized the concept, when she created men’s skirts for a joint exhibition with Rudi Gernreich entitled “Two Modern Artists of Fashion,” which took place at the Fashion Institute of Technology in April of 1967. Hawes and Gernreich had become friendly earlier in the decade when both were living in California, the basis of their friendship no doubt being rooted, in part, on shared viewpoints on gender and dress. Gernreich would later make headlines in 1970 with his unisex collection that attired bodies identically, including the pairing of topless male and female models sporting matching shaved heads and belted micro-mini skirts. [15]

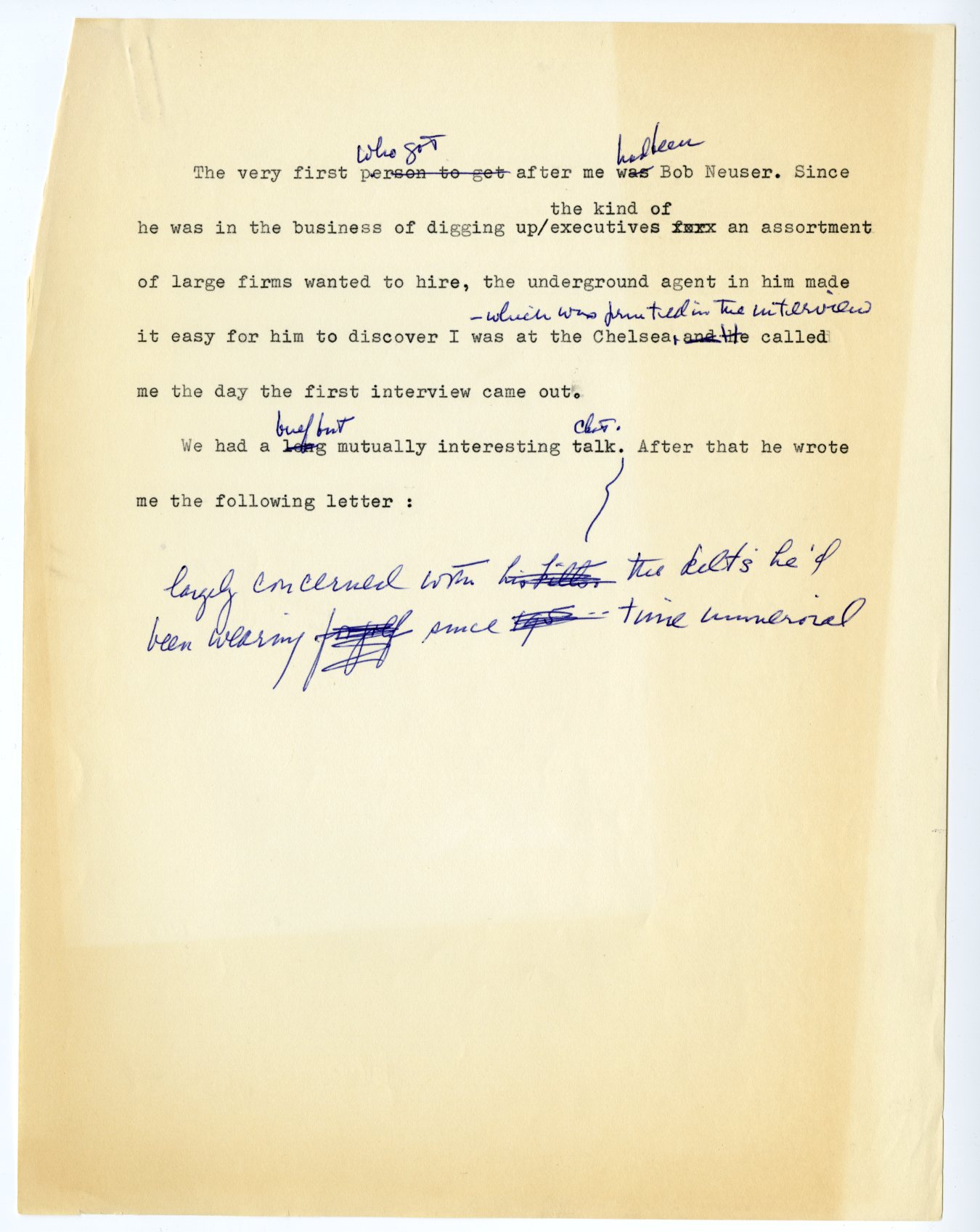

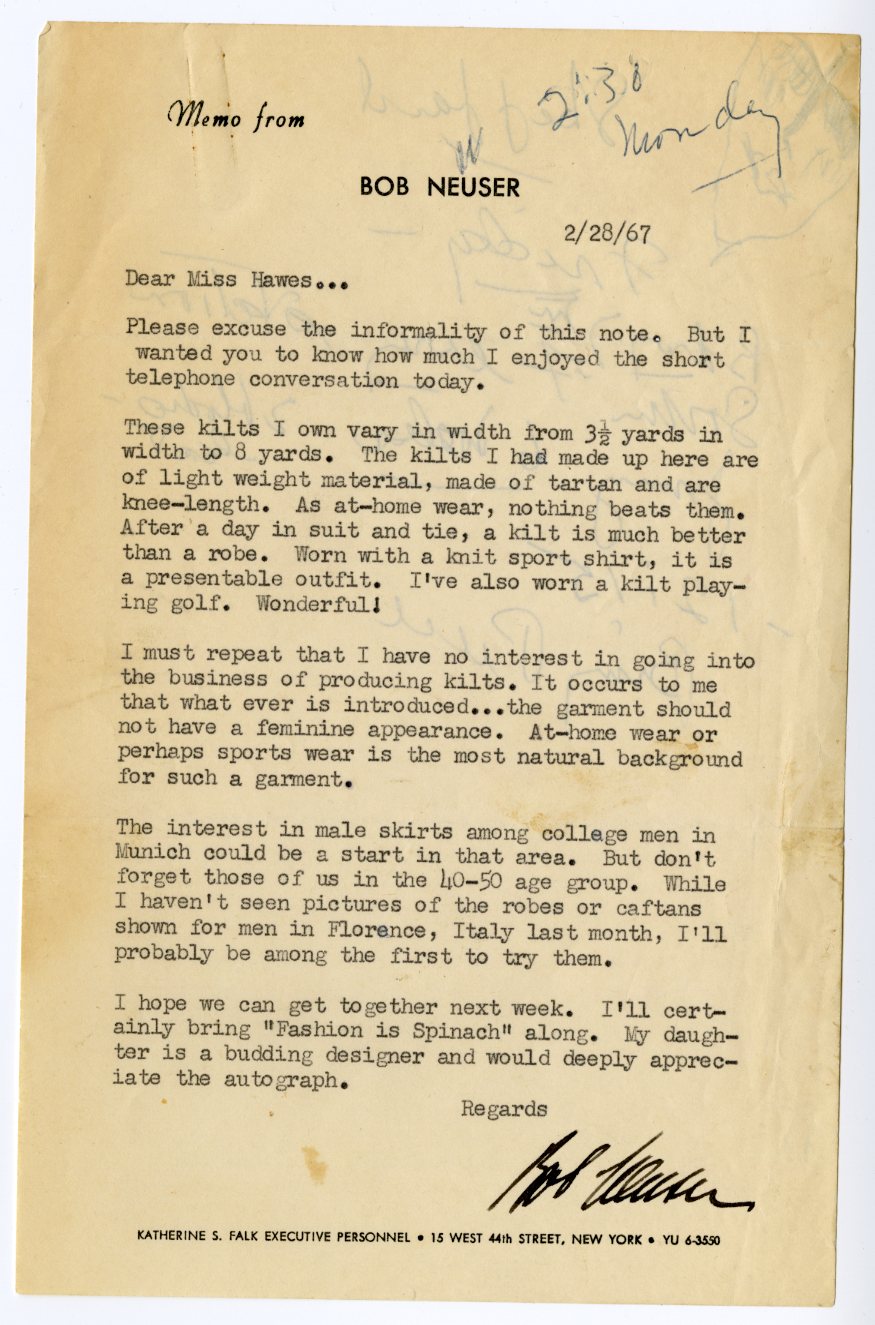

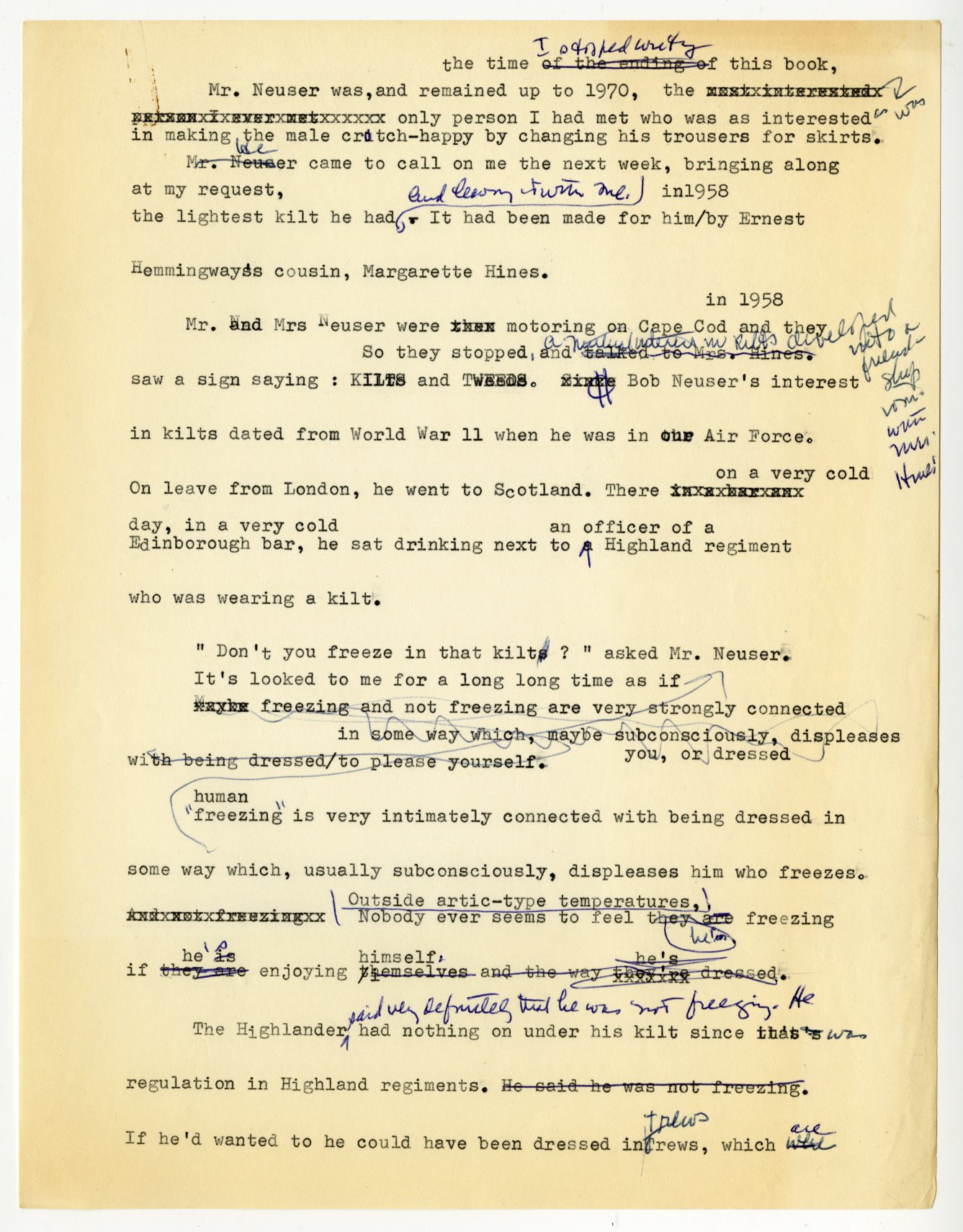

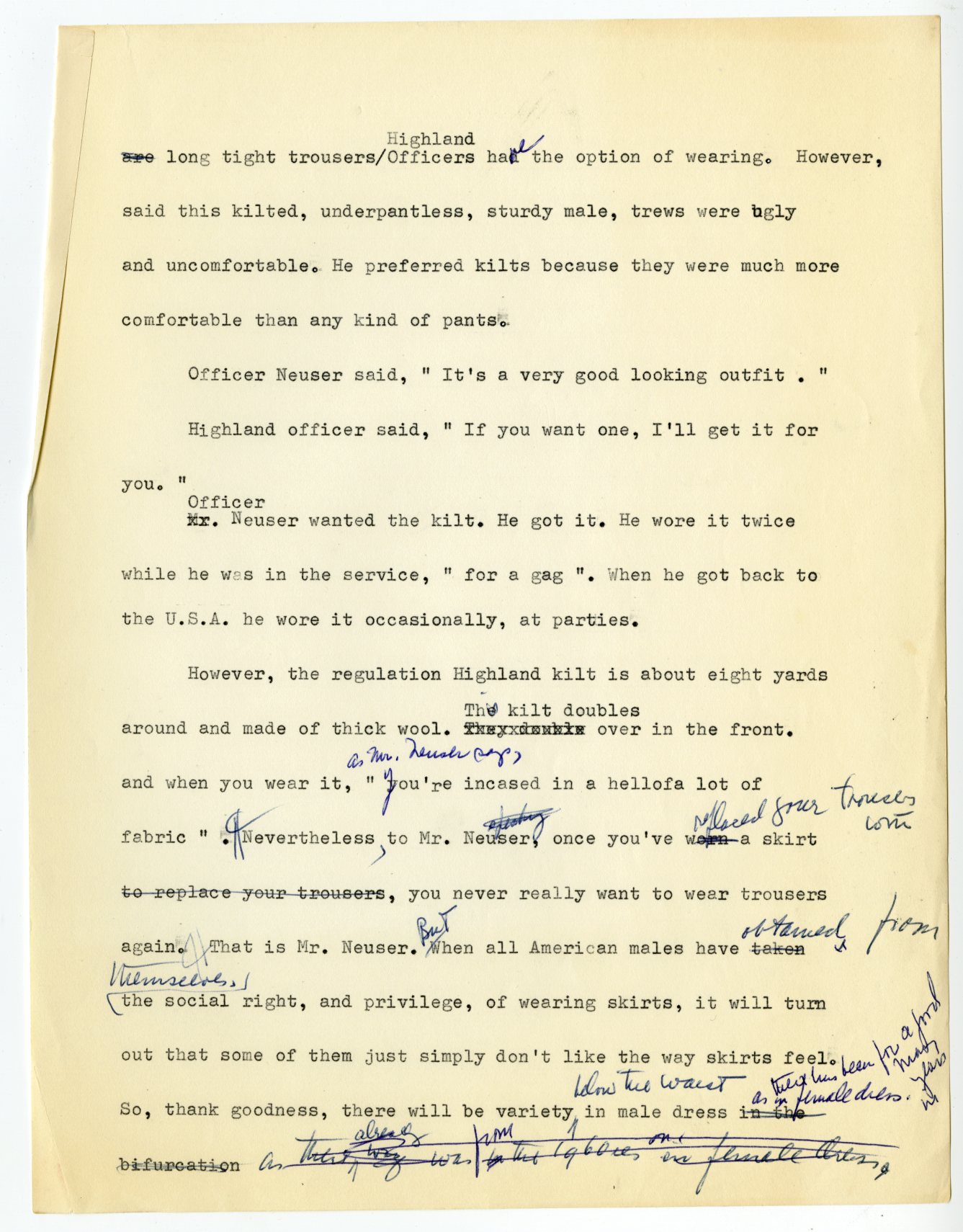

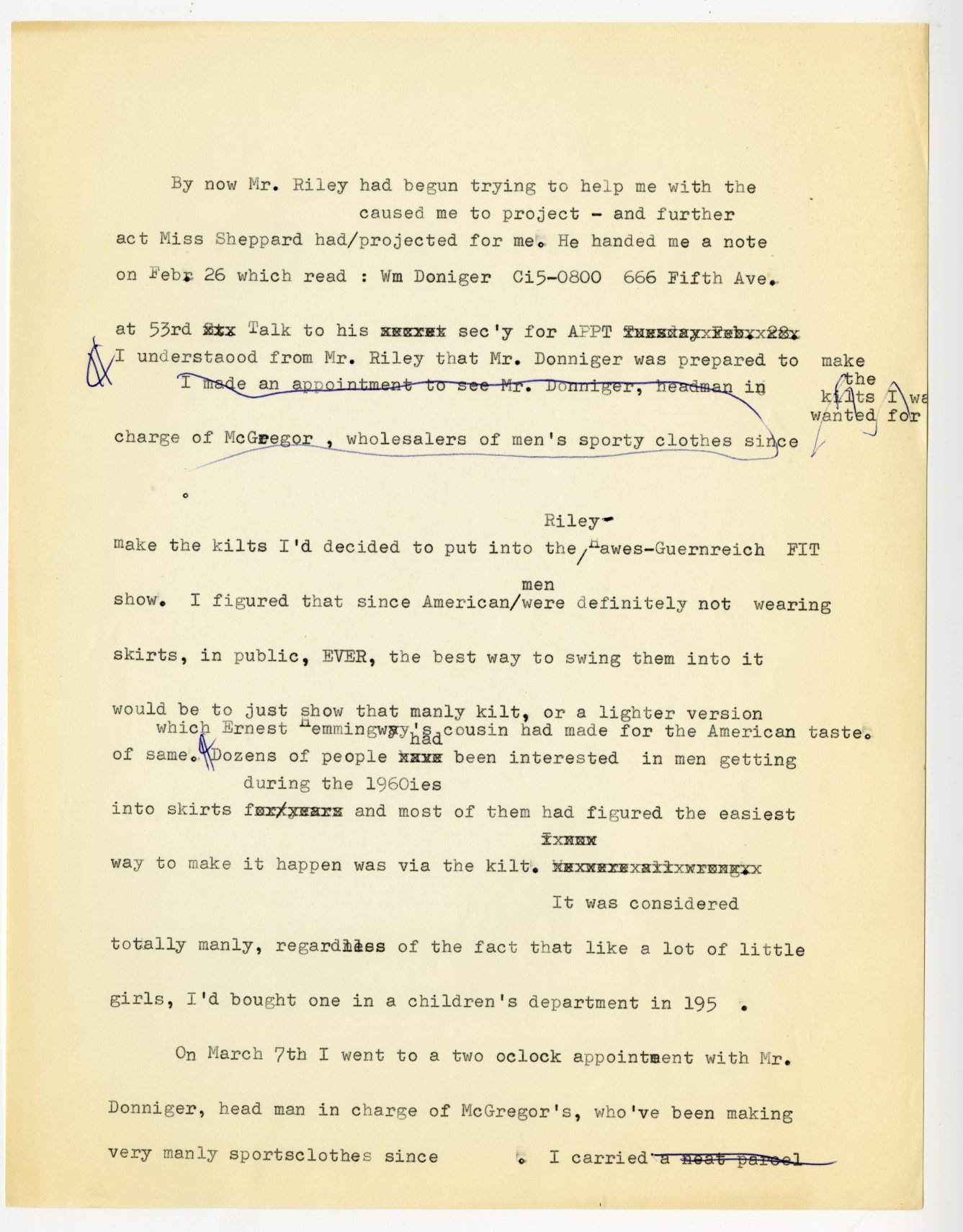

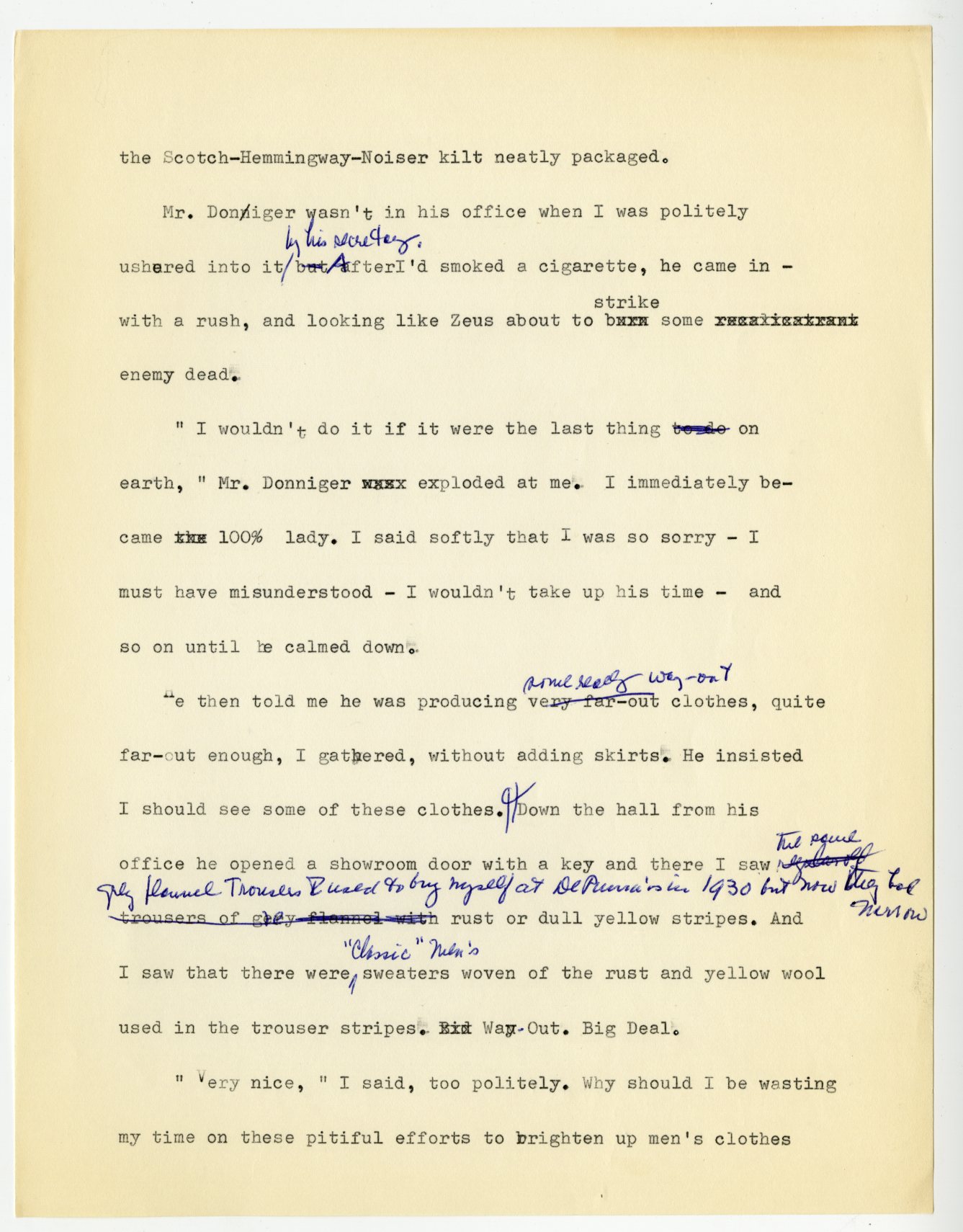

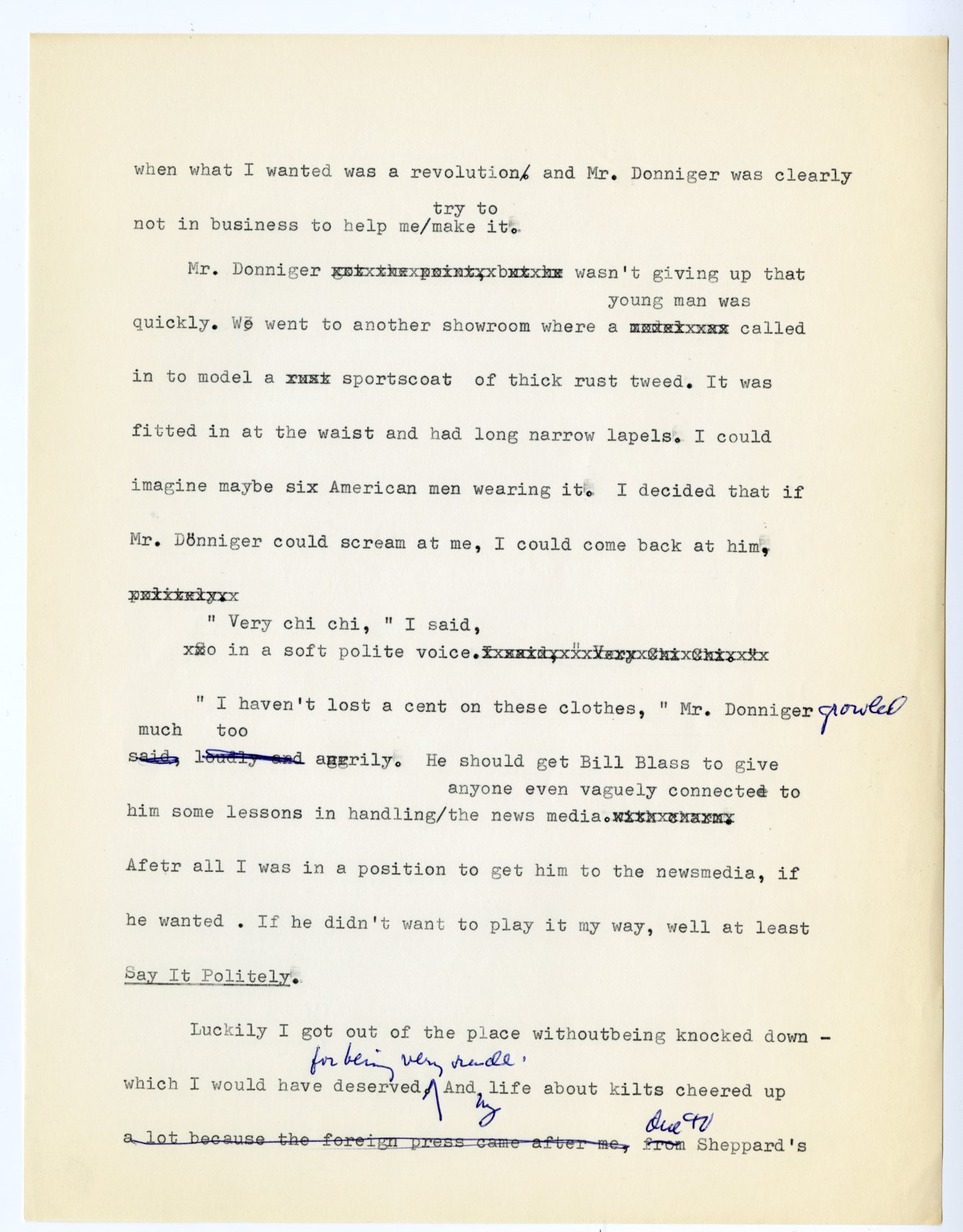

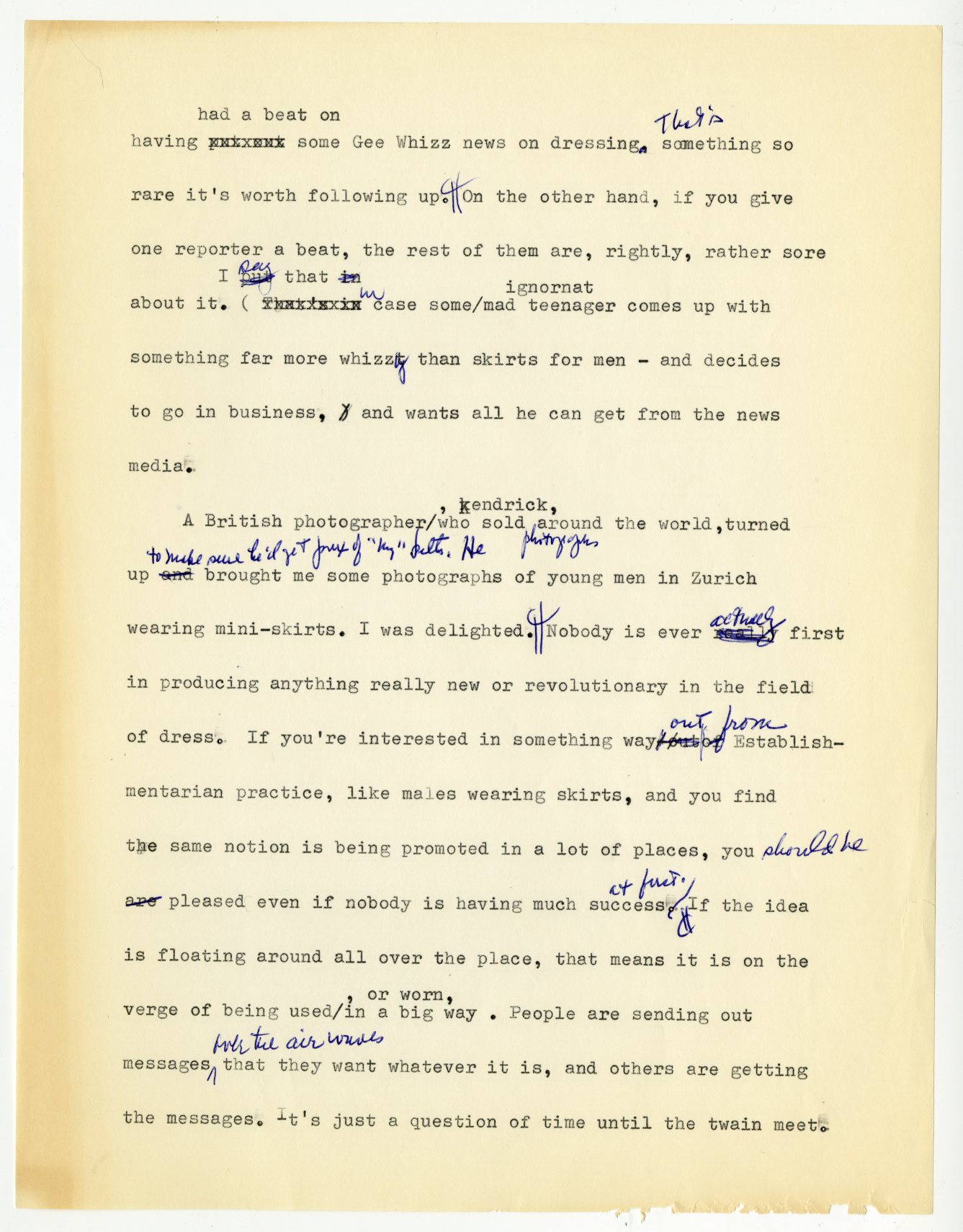

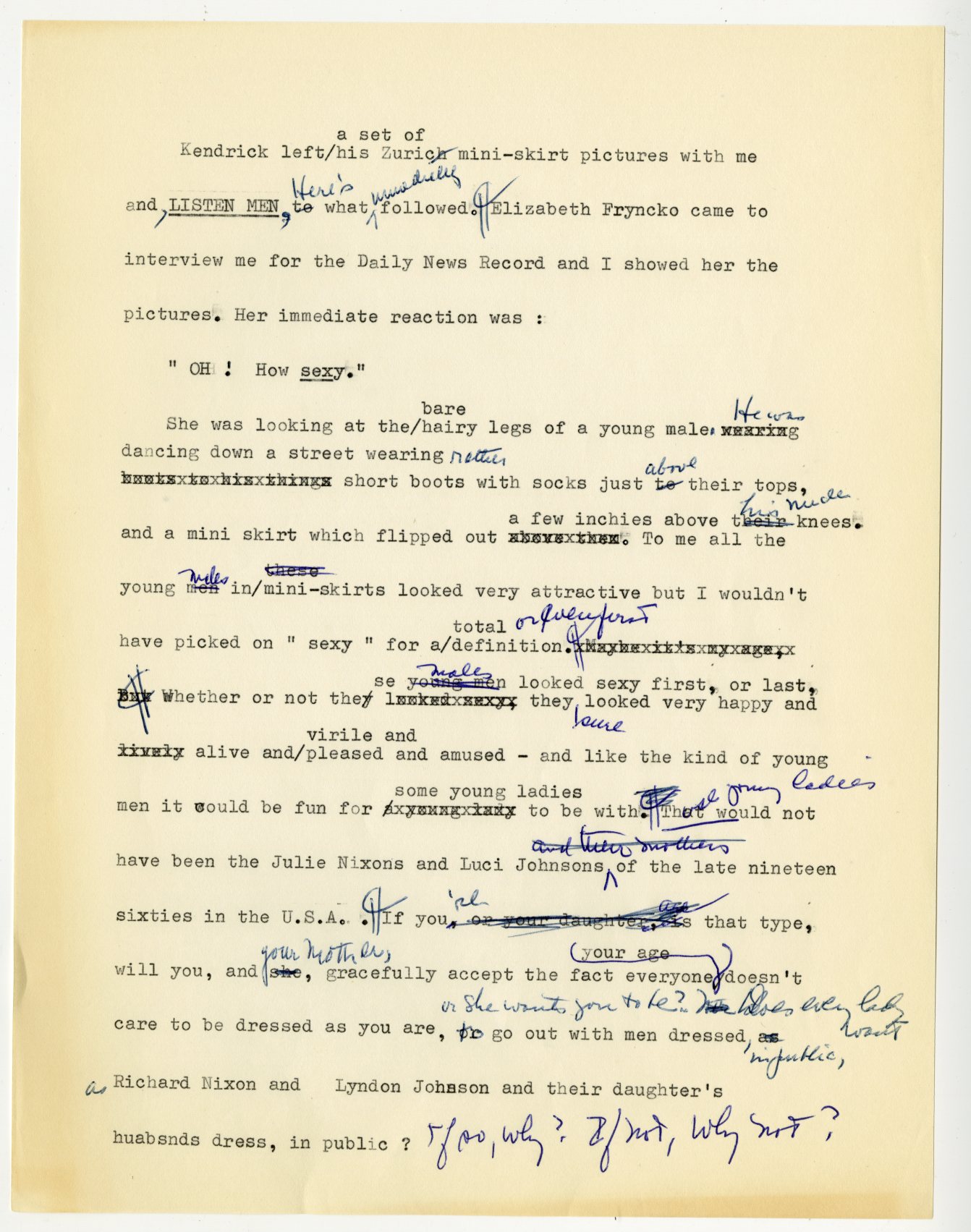

In the unpublished treatise “Me & Skirts & Men” reproduced here in this article, Hawes records her experience launching one of American fashion’s first efforts to endear men to skirts. Her, “deep and old old desire to help American males be comfortable and attractive had been lying dormant publicaly [sic] for thirty years.” [16] Admittedly, following the 1967 exhibition, “the campuses and golf courses of the U.S.A. did not immediately blossom with males in skirts, or kilts if you prefer,” but the concept received significant press coverage and four members of the NYU baseball team controversially appeared on television modeling Hawes’ designs. [17] Actor Tom Poston practically spit fire, denouncing Hawes as, “a public menace who had the indecency to publically threaten the masculinity, the hard won rights, the very manhood and heart of America.” [18]

“When will American males be as free to dress to please themselves as our females now are?” posited Hawes. [19] Fifty years later, this question still remains part of the contemporary fashion discourse, with the skirt standing alone as one of the last “gendered” garments. Just as in the 1960s, this un-bifurcated garment has been adopted by today’s most avant-garde. Actor Jaden Smith made headlines around the world when he appeared in the 2016 Louis Vuitton womenswear ad campaign wearing a skirt alongside female models. Visionary fashion designer Rick Owens has repeatedly promoted this alternate version of masculine attire in his menswear collections, as has designer Thom Browne, who most enthusiastically embraced the skirt in his recent menswear collection for spring/summer 2018.

Where there is rebellion, the blurring and disappearance of gender lines will only continue, perhaps making the intriguing appearance of be-skirted gentlemen that I see on the subway with increasing frequency not such a novelty after all. They are a pure delight to witness, and I cannot help but smile to myself thinking, in the spirit of Elizabeth Hawes, “fashion has gone to hell.”

Notes

[1] Hand-written note by Elizabeth Hawes, undated, box 2, folder 6, Elizabeth Hawes Papers, FIT Special Collections and College Archive, Fashion Institute of Technology, New York, NY.

[2] Correspondence addressed to Elizabeth Hawes, August 13, 1969, box 2, folder 6, Elizabeth Hawes Papers, FIT Special Collections and College Archive, Fashion Institute of Technology, New York, NY.

[3] Elizabeth Hawes, Fashion is Spinach (New York: Random House, 1938), 133.

[4] Elizabeth Hawes, Why Women Cry: or Wenches with Wrenches (New York: Reynal & Hitchcock, Inc., 1943), xvii. Additionally, a New York Times article dated February 1, 1940 cites Hawes’ interest in experimenting with designs for mass production in order to place her designs in reach of those with, “an average American income.”

[5] Ibid, 69.

[6] Bettina Berch, Radical by Design: The Life and Style of Elizabeth Hawes (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1988), 2.

[7] Unpublished manuscript notes entitled “Who’s Talking,” January 1970, box 1, folder 2, Elizabeth Hawes Papers, FIT Special Collections and College Archive, Fashion Institute of Technology, New York, NY.

[8] Hawes would die early September 1971 from cirrhosis of the liver, following years of heavy drinking. Berch, 189.

[9] Unpublished manuscript draft, undated, box 2, folder 9, Elizabeth Hawes Papers, FIT Special Collections and College Archive, Fashion Institute of Technology, New York, NY.

[10] Time Table- Public Life, undated, box 1, folder 11, Elizabeth Hawes Papers, FIT Special Collections and College Archive, Fashion Institute of Technology, New York, NY.

[11] Unpublished manuscript draft, undated, box 2, folder 9, Elizabeth Hawes Papers, FIT Special Collections and College Archive, Fashion Institute of Technology, New York, NY.

[12] Unpublished manuscript notes entitled “Who’s Talking,” January 1970, box 1, folder 2, Elizabeth Hawes Papers, FIT Special Collections and College Archive, Fashion Institute of Technology, New York, NY.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Elizabeth Hawes, Fashion is Spinach (New York: Random House, 1938), 291.

[15] Rudi Gernreich: A Retrospective, 1922-1985, ed. Jacques Faure (Los Angeles: The Fashion Group Foundation, 1985), 43.

[16] Unpublished manuscript draft entitled “Me & Men & Skirts,” undated, box 3, folder 8, Elizabeth Hawes Papers, FIT Special Collections and College Archive, Fashion Institute of Technology, New York, NY.

[17] Unpublished manuscript notes entitled “Who’s Talking,” January 1970, box 1, folder 2, Elizabeth Hawes Papers, FIT Special Collections and College Archive, Fashion Institute of Technology, New York, NY.

[18] Unpublished manuscript draft, undated, box 2, folder 13, Elizabeth Hawes Papers, FIT Special Collections and College Archive, Fashion Institute of Technology, New York, NY.

[19] Unpublished manuscript draft, undated, box 2, folder 4, Elizabeth Hawes Papers, FIT Special Collections and College Archive, Fashion Institute of Technology, New York, NY.