My Mum's Sunday Best

My mother was born in Montreal in 1940, and I’ve always thought that her life rode the waves of the second half of the 20th century in kind of a tidy narrative way. Her father was away at war until she was 6. In the 50s, she was a teen bobbysoxer and a cheerleader out of an Archie comic. In the 60s, the travelled the world, settling for a time in London at the height of that decade’s big Swing. She returned to a rural hippie paradise for a few years, then straightened out but stayed crunchy in the mid- 70s, getting involved in adult education, conflict resolution, group therapy, breastfeeding research, and all kinds of hopeful grassroots political movements. Then I was born and it gets a little boring after that. Sorry, mum!

Alongside these changes in her lifestyle, echoing what was going on in the culture, she’s also taken a bit of a wild ride through various religious affiliations. She started as the granddaughter of a Baptist minister, dutifully attending church every Sunday, but that faith was shaken from the time of her first serious relationship. Later, she went on an almost-cliché spiritual journey through those hippie years, but never left religion behind entirely, and eventually came back to Christianity in a pretty heavy way. By the time I was a child, she belonged to a Charismatic Catholic prayer group in which she was the only non-West Indian member. She would sometimes speak in tongues over my bed when I was sick, thumbing a smear of holy water on my forehead. I have a lot of weird memories from that time.

Finding out how she got from point A to point B has been an enduring conversation between us throughout my life. I’ve always been curious how someone could leave Christianity, see what else was out there, and then come back to it with such a vengeance. To be fair to her, her involvement in 2017 is pretty low-key; even the Cool Pope couldn’t keep her Catholicism intact and she’s now a member of the United Church, a chilled-out Protestant denomination that’s pro-gay, pro-choice, etc.

As a fashion researcher and member of the FSJ team, I of course believe that any story worth telling can be told through clothes. Not too long ago I was editing a collection of academic works about fashion and religion. It was really interesting stuff, like about the religious history of Trinidadian Carnival costume, and ethnographies of Orthodox Jewish women’s dress practices. There was a great and diverse range of subject matter, but my mind kept returning to these trunks of mysterious, musty clothes in my parents’ basement. Clothes I had pored over for years when I lived there, looking for clues about my mum’s past life. I had a feeling that her fashion history was some kind of shadow of her religious one, and that, if I looked, I would find them to be tightly woven together.

This interview with her is part of that process of looking. All the photos are her own.

Laura: Can you tell me about dressing for church when you were young?

Rosemary (Mum): I remember being 4 and 5, and I had a straw hat something like my sister’s, who was five years older. Hers had a brown ribbon around it and mine was navy blue. I was always happy to dress up like her. I remember putting on a dress that had smocking on it, which was like a "best dress," a party dress. And party shoes, patent leather, with white socks.

My mother didn’t come to church, because her father was an evangelical sort who’d taken his 11 children to church 3 times every Sunday, so [she’d had] enough. It was wartime, so maybe she wanted us to pray for our father or something. I don’t know. But anyway, the idea was more that it was fun. You sang all these lusty old songs.

L: Were other children dressed the same as you?

R: Oh yes. They had on their hats and a dress, and little party shoes, and there was always a little purse. Always a great little purse that was a church purse. You’d bring collection. And a Kleenex. In hindsight, we would be a little less well-off than most of the kids I went to school with, but I never felt that. I always felt that my Sunday clothes were as good as theirs.

L: What did you wear for special occasions?

R: Well for instance, for confirmation, you wore white. Our neighbor upstairs was smallish in stature, so we were about the same size when I was 12. She lent me a very nice white round-necked dress with ¾ sleeves and a nice waist and a gathered skirt, so this dress felt very elegant. I still wasn’t wearing high heels, but I think I had a patent leather slipper kind of thing. Oh, there was a veil!

L: Were these clothes uncomfortable?

R: A little bit, but of course, everything about church was uncomfortable. It was sort of like Sunday dinner. You dressed at the table for Sunday dinner, and it was a bit uncomfortable having to have your manners be perfect. Sunday was a day for discomfort (laughs).

L: Was the tradition of dressing for Sunday dinner religious in itself?

R: Well, the church and the dinner following it were tied as the core of the day. So even though my father didn’t go to church, [my stepmother] did, and [my brothers] would have on their short pants, suit jackets, ties, white shirts, and they would keep those on for the dinner. And you had this sense [at their house] of being of the right class, both in church and then followed through at home. My mother didn’t tend to dress up for Sunday dinner because she was busy in the kitchen cooking it, and serving it; I mean, she was doing it all.

L: Did you or anyone else in your family ever have any crisis of faith?

R: Well, [my sister] dropped out when she had [a baby], when she was 17. She stopped going to church when she became pregnant, so from 16 on she hardly set foot in a church. She also became angry about church. I think she didn’t want to have to cope with any sense of shame or the judgment, and [her boyfriend’s] family were high Anglican and his grandfather had been an archbishop, and so there was real stiffness and religious conformity in his family, so the two of them determined they weren’t going to raise their children in any Christian fashion.

But I kept going to church until I began to go steady [with my boyfriend Ian], in grade 11. Ian’s family were Presbyterian. My father, who by now was re-married, was pretty disgusted by that. And when I said that Ian and I talked about getting married one day, he said, “Well, you wouldn’t get married in the Presbyterian church, would you?” and I said, “Well, possibly,” and he said, “Well, you just shouldn’t do that, because you’re not going to make your way in the world without the Anglican church.” You know, all the leaders of the country, and the Queen, they were all Anglican.

When I went to church with Ian, I’d wear a suit. I think by then I had two suits, a mauve one and a poppy red, so I wore a suit and a hat. There were milliners all around the place, so you could sit in front of a mirror and try on wonderful hats, and by then I would wear high heels and nylons. Nothing in my case was prim, it was just dressed up.

I think [the end of my church-going] was fairly abrupt. I was probably 17. Since confirmation I had been reading a particular little Anglican prayer book every night and was really serious about prayer and then as I read this little book very carefully -– it was a lot of the Anglican rules and such –- and clearly, one was not going to be permitted to engage in anything akin to sexual activity, and I just felt at 17 and 18 that taking that route didn’t give me any options. I wanted to keep my options open, and that therefore I didn’t have enough religious integrity, and so I couldn’t really stick with them.

L: What options were you left with?

R: Well, at 18 and 19 and 20, we were just moving into the 60s, and there was a lot of questioning of a lot of things. So I stayed disconnected from organized religion for a long time, but I did explore, like a lot of other people at the time, Zen Buddhism, and then Ron Dawes came along. His version of Hinduism was very appealing, and the notion of really knowing who we are, and not living by rules. So dressing rules got kind of tossed. And I didn’t have a "Sunday best," but I liked all the clothes I had, and I had lots of paisley and interesting things. But it was a long time though before it felt okay to do anything you wanted on a Sunday.

When I was [playing] with the band, the biggest practice was Sunday, and it often did feel funny to me. By then I was in my early 30s and it was still a feeling like, "Oh gosh, it’s a bit of an odd thing [to be playing rock music on a Sunday]."

L: Did it feel like the rest of the world was shedding organized religion along with you?

R: Right around that time, I remember taking a drive into Verdun, down by the Lachine canal, and there people paraded in their Sunday best, and this was in the 60s, so among Catholics, it didn’t alter for a long time. And the little girls really were dressed up, lots of ribbons and full skirts and organdie, and ringlets and hats. And men in suits, women in nice dresses, and their children paraded along the canal, along the walkway. So others were keeping it up, but I wasn’t.

L: So what did this experimentation with Eastern religion look like, in your case?

R: Reading, putting certain pictures on the wall, you know, having a picture of Shiva, having a little Buddha sitting somewhere, lighting incense, keeping the lights low. You didn’t have bright overhead lights. Somehow the sacred was all connected to quiet, and darkness, and then I built myself a little prayer cupboard in the farmhouse [I was living in] in my late 20s, so I could sit in there behind this paisley cloth and light the incense and learn to meditate. I was alone for much of the time during the day for two years, so I would try to, about 3:00, have a half hour to an hour in the meditation cupboard (laughs).

L: What did your clothing look like at that time?

R: I would try to wear clothes that were sort of flowing and feminine, because there was a big emphasis on male and female in the hippie years. The hippie culture honoured women in their housewifely duties. The men would sit outside and clean the guns. This is when we were in the country. But the women’s job was to honour the man with sewing for him, because you tried to stay out of the commercial world; so a woman who could embroider beautiful things on the shirt she’d made for a man… you know, a loose, flowing, linen shirt, she would be really considered special. And then the women also made goods for sale. They made leather goods, necklaces, belts, purses. So the women were crafty, domestic, oriented to be with each other, and the men talked serious business and protected the women, and… talked serious business. (laughing) I don’t know what they did! And everybody listened to music and was stoned a lot of the time. Now, the women were allowed to be stoned, they weren’t kept from going places, they weren’t kept indoors, but what they aspired to was to be gloriously, productively domestic. Good cooks, good bakers, everything. You made your own bread.

L: Do you think there was a connection between the clothing and the values of these religions you were dabbling in?

R: Clothing was very important. It was no longer Sunday best, but you wanted to look a part. You wanted to signify that you were spiritually oriented.

Some of us knew people who were bringing those fabrics (from the east), and then [my friend] Dalton had a manufacturer in India, and he would make designs, and they would make them up. Indian sort of bedspread cloths. He would bring them back here and we’d snap them up. The spiritual practice among people I knew was a mixture of Buddhism and Hinduism, but filtered through American authors (laughs). I don’t know. A lot of people had gone and spent time in India, you know, think of the Beatles. It was a combination of psychedelic drugs and fetishization of the culture in India, which seemed very laid back.

L: You had a lot of those clothes and materials around the house when I was growing up. But by then you were really Catholic. What was that like, when you found Catholicism in your late 30s?

R: Well, I was also a PhD student at the time, and joining the [on-campus] Newman Centre had an intellectual component. We’d have a little mass sitting around the floor with a priest, but the scripture was open for everybody to talk about and discuss and debate. There was more questioning. There were a lot of people who were like myself and had emerged from a time of not being religious except in an Eastern way. So there were certain Eastern elements.

L: Like sitting on the floor!

R: Yes, good point. (laughs). There was great freedom in that you didn’t dress up on Sunday. The priests did, yes. They tended to wear a white shawl. And when someone became a priest, if they were in a more traditional church, their family and friends would give them colorful robes for different seasons, but at the Newman Centre, if I recall, when a new priest came in, they would give them a nice shawl. Not a shawl, what do you call them? It’s something like, possibly, what rabbis wore.

For church I might wear loose cotton pants and a colorful top. Sunday best dressing was only at Easter, and I would always be sure I was wearing something yellow, bright, special beads. But one woman, who was the most interesting person, had a beautifully woven, Israeli robe. She had been Jewish and converted, and then she wore a turban at Easter around her head. The Newman Centre allowed for a wide range of ways of living your faith, which included clothing.

L: When I was a kid, the Catholic church we went to was really diverse, and I remember there was more of a dress-up spirit among the immigrant communities who went there.

R: Definitely. I usually just went with what I had, but I didn’t want you to wear your play clothes. [Your god parents’] family was always dressed up for every Sunday. I think it was the lasting impact of colonialism on the religious practice in the West Indies. They looked wonderful.

L: But you wouldn’t let me wear the type of First Communion dress I wanted, which was what all the other girls had.

R: No, I couldn’t quite let myself get you the kind of bridal gown and veil that the other little girls were wearing. I suppose it was my British Protestant beginnings keeping me from it. The Italian and Portugese girls were fully turned-out in their gowns and veils and gloves and high heeled shoes. And you wanted to dress like that too, but something stopped me and we ended up with something much more modest.

Our conversation ended there, because the last thing we needed was for me to start in on my list of grievances around what I was or wasn’t allowed to wear as a kid. But as I look at the photos she shared with me following our talk, I see so much: the imposition of British norms and standards on the still-young communities of the colonies; mid-century beliefs about children as little adults-in-training better seen than heard; a young woman straining against the expectations and restrictions placed on her body; communities forming in the wake of cultural revolution; an individual looking for structure and direction throughout personal and societal upheaval. I see my mother, her generation, their victories against many forms of repression, and even their ultimate imposition of new ones.

I don’t intend to present her story as universal: she’s always been a roughly middle-class, cis-hetero, white settler to Canada, and that means that experimentation with clothing, religion, psychedelic drugs, and playing in a band called Fuck Pig have all held few negative consequences for her that would not be the case had she inhabited a different identity. Still, her decades of (well-documented!) dressing up on Sundays shows us just how central a role clothing often plays in navigating one’s spiritual life. And besides, she’s the only mum I’ve got, and I love her. Happy mother’s day!

Photo Captions

1. Mid-1950s, in her church suit.

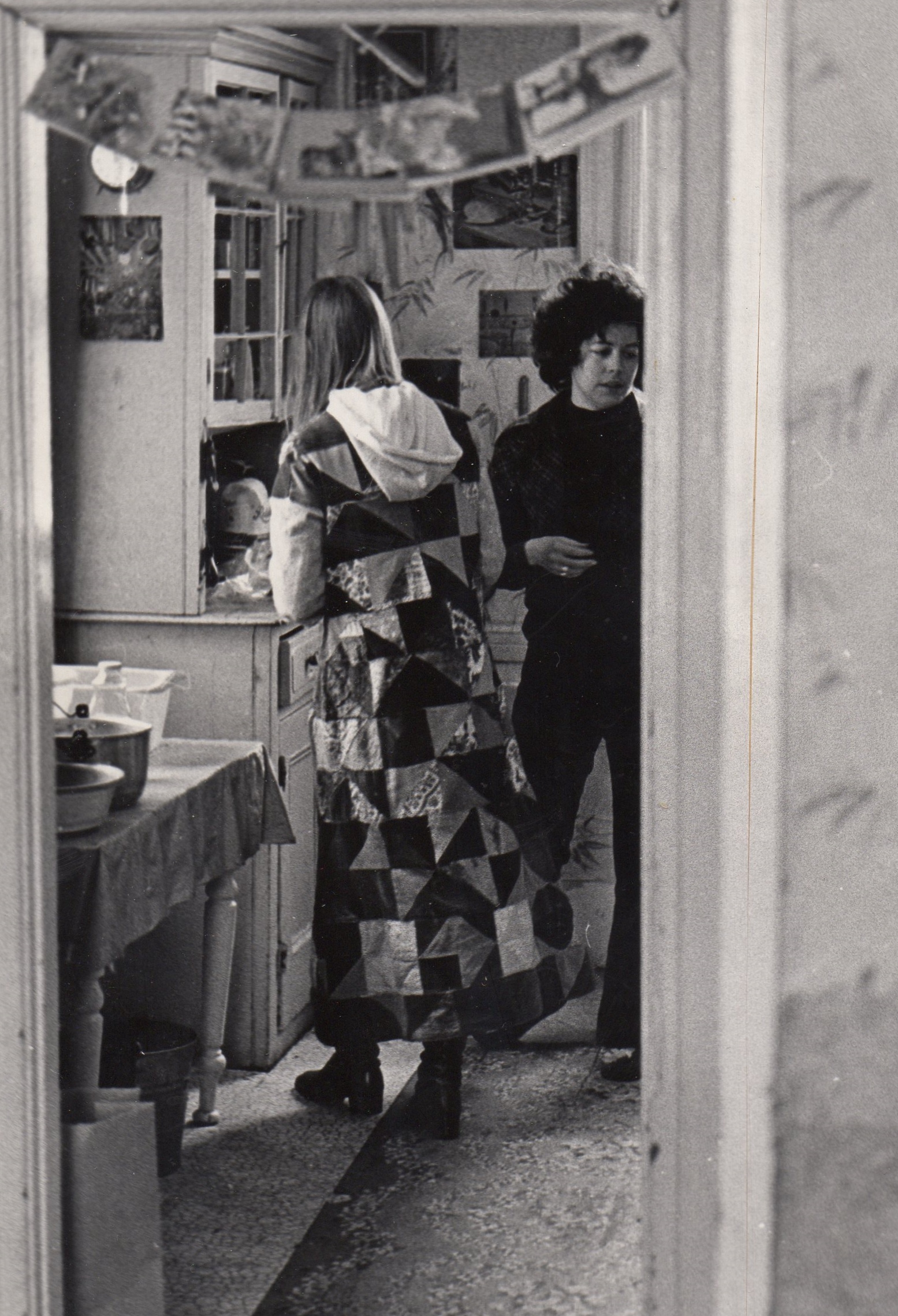

2. 1971, with a friend in a homemade patchwork robe.

3. 1973, with friends on the farm in the Ottawa Valley.

4. 1975, in British Columbia.

5. 1979, with my dad (seated) and friends; she calls this "post-hippy."

6. My godparents (center) heading to church with family on an ordinary Sunday, late 1980s.

7. Me and a friend outside church in Toronto, circa 1990.