My Mother, Dress, and Dementia

How I choose to dress is central to my identity; I fashion myself daily using clothes to shape, communicate, and perform who I want to be at that moment. I learned all this from my mother. As a child, I watched closely as she negotiated the various roles she played via her relationship with her wardrobe. This was a relationship that felt, at times, more central to her self-identity than being a mother ever was.

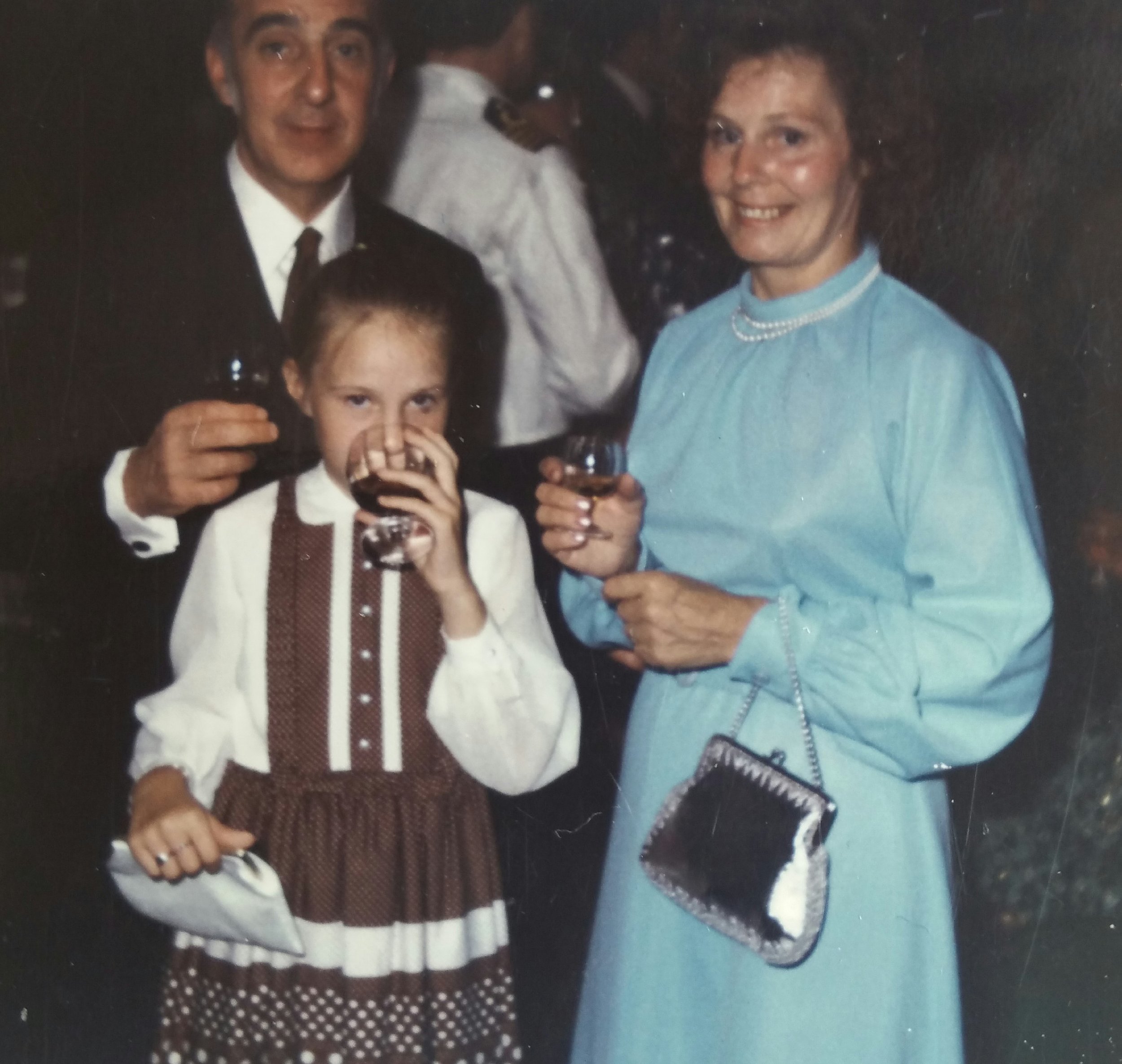

I recently wrote about why I care about what I wear, how I longed to grow into my mother’s wardrobe, and how her dementia has changed her bond to fashion and the effect that has had on our relationship. Clothes—both my mother’s and my own—are substantial material objects in my personal biography. My memories of our relationship are preserved in the outfits we wore. These “memory objects,” which evoke and materialize, prompting entangled emotional reactions, are so powerful that I wonder whether the feelings belong to me, or rather, are a part of her.

The fabric of our love has been stretched, shredded, and patched over the years. And now that she is in a nursing home with dementia I feel that fashion may be the only meaningful way that we can still relate to one another. When I visit her, I therefore dress to please her. With my frocks serving as a trigger, she inevitably always comments on how I look, we talk about her favourite dresses from the past, and I make sure she always has photos that will prompt her recollection of herself as being-in-the-world: an antidote to the smallness of her life now contained as it is between her bedroom, the day room, and the lunch area. She no longer has a need to dress for appropriate occasions; she is now just a person whose singular identity is wrapped up in the constraints of dementia.

Julia Twigg proposes that dress has considerable relevance to the lives and well-being of people with dementia and just because they are no longer capable of agency, expressivity or consumption shouldn’t exclude them from the pleasures of fashion.[1] I’m lucky that my mother is being cared for in an environment that understands this need. I am aware when I visit that she has been helped to dress in a way that still reflects who she is, her dresses, matching cardigans, her love of drapery—always a swishy shawl thrown around her neck just so—encourage me to see her as ‘herself’ as opposed to a patient. She hasn’t liked trousers for a good while, skirts fall off her as her weight diminishes, so it is always a dress; soft, pretty, often jersey, her version of comfort dressing. I want to wrap myself around her to comfort her further. Instead, I fetch her another shawl to replace the tea stained one and hug her tight as I place it nonchalantly round her tiny shoulders. I can’t help smiling as I think how much she would have loved to have been this effortlessly thin in her younger-always-dieting days. It’s not only her way of dressing that creates this continuity of identity, however. She has a manicure every few weeks and she always wears lipstick when I visit. I set her hair and we chat whilst it dries; as I comb her out, she emerges from her timidness and sits up taller.

Moving into a residential care home was not what I imagined for my mother. I didn’t anticipate her memory loss, the loss of her beauty and style, nor the loss of her personal possessions, including many of her garments. These losses, however, have not disrupted our connection. Rather, we use our dresses to access our shared memories, our mutual biographies, and the thread of identity that creates continuity for our imbalanced relationship. Just as it always has.

Notes

[1] Julia Twigg, “Clothing and Dementia: A Neglected Dimension?” Journal of Aging Studies, 24(4): 223-230.