What's so Fashionable About HIV?

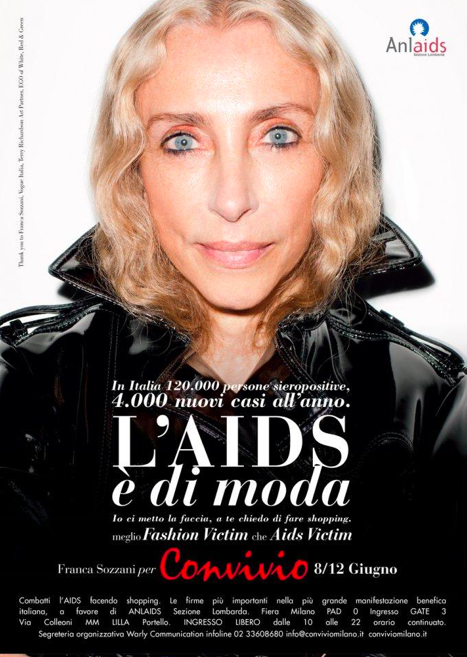

On June 1, 2016 an advertisement reading “L’Aids é di Moda” (translatable as “AIDS is in fashion” or “AIDS is of Fashion”) was released to promote Convivio, a charity event organized in Milan by the Italian fashion industry to raise funds for Anlaids, the association that supports HIV/AIDS research in Italy. It quickly went viral in the media, triggering two main reactions: some praised the courage of opting for a high-impact message while others found the copy troublesome, ambiguous or even offensive. The global fashion industry has been active in sustaining medical research since the start of the epidemic. Nevertheless, there is a web of ties between fashion and AIDS that appears quite disturbing, and which has gone largely uninvestigated: in this essay, I will trace the visual connections between safe-sex advertising campaigns, often shot by fashion photographers, and un-safe gay sex practices. More precisely, I will examine the bodies portrayed in the ads in order to explore how their visual representation may have unintentionally contributed to engendering a problematic glamorization of HIV.

However, as will become evident toward the last part of this essay (despite the highly problematic nature of the ads), I will avoid stigmatizing the bodies partaking in what I read as unsafe sexual practices; rather, I will suggest that, morality aside, these could be reanalyzed under an alternative light. I will be looking at radical sexual behaviors through the lens of fashion due to its singular capacity to shift and remold bodily borders. With "fashion," I hereby refer to practices of (self-)fashioning consisting of forms of body modification, both visible/external, e.g. tattooing or piercing, and invisible/internal, namely, as we will see, the circulation of pathogens. Fashioning, from my perspective, has to do with a body that is not only "seen" but also "felt" insofar as it is simultaneously a perceiving subject and a perceived object in constant flux, being rearticulated in a variety of forms through its being in the world and its being with others, a permeable membrane that absorbs, manipulates and reflects affects, images and discourses. In other words, in this study fashioning is "affective"[1] in that it allows (queer) bodies to become other, to project themselves beyond normative structures.

More broadly, this essay seeks to unpack how masculinity, together with concepts of "risk" and "health," is embodied in images from HIV prevention material targeting a gay male audience and how, through their streaming and modulation with the viewer’s body, such images become affective, thereby potentially informing our ideas and identifications. I will approach the pictures under study as visual narratives unfolding modes of belonging and collective bodily fantasies: in other words, as a fluid repertoire of embodied practices and knowledge. To conduct my analysis of safe-sex ads, rather than resorting to the tools offered by semiotics, which may prove too rigid and not take into account the aesthetic, sensorial, and affective experiencing of the images, I will employ queer and affect theories to plough through theoretical knots and open further avenues of reflection, encouraging the reader’s curiosity to think through the images under examination. In doing so, I will suggest unconventional paths of interpretation that aim to go beyond meticulously descriptive methods of analysis, without any attempt to demonstrate an argument or the presumption to establish "meanings" for the images under study.

Glamorous Hyper-Masculinities

After the Stonewall Riots in 1969, gay men living in metropolises across the United States and Europe started to reject their stereotypical association with effeminacy by adopting a new “butch” look, comprised of combat boots, leather jackets, sleeveless t-shirts, and tight jeans emphasizing the buttocks and the genital contours,[2] in order to perform an über-masculinity, simultaneously negotiated in the gym through strenuous training sessions, and based on the fetishization of working-class masculinity. This subcultural style thereafter came to be known as “gay macho” or "gay clone."[3] During the 1980s, a mainstreamed and fashionable version of the gay macho started to propagate into many gay nightclubs, which, as a result, became an elitist space reserved for men who conformed to specific physical parameters, contributing to the disintegration of values of inclusiveness and belonging and establishing, through the celebration of young muscled bodies, a paradigmatic male aesthetic known as “New Man.”[4]

Such new staged imagery—having been commodified for commercial purposes by the advertising industry—was integral to the gym obsession running parallel with the spread of AIDS: the increased muscularity of gay male bodies was both a reflection of the new male consumerist ethos and a reaction to the epidemic. I argue, in fact, that in the late 1980s the AIDS epidemic dramatically changed gay men’s physical self-perception and encouraged them to conceive the gym as a lab in which to reshape their identity by redesigning their bodily appearance. I would suggest that weightlifting for HIV-negative individuals became a medium through which to exorcise the fear of the disease and, by extension, of death, and for HIV-positive men, a practice aimed at constructing an armor to mask or hide the diseased body. Since the 1990s such "anguished health consciousness"[5] has become widespread within the gay community and, as a result, incredibly fit bodies have made their appearance even in HIV prevention material: the association of highly desirable bodies with HIV led to a "glamorizing [of] sick bodies"[6] which could potentially have critical consequences on the level of social perception of HIV among gay individuals.

The first HIV prevention ads featuring gay couples and shot by fashion photographers were produced in the form of street posters by the Red Hot Organization for the ‘Safe Sex is Hot Sex’ campaign in 1991. Bruce Weber and Steven Meisel took a series of pictures blatantly aestheticizing the models through a savvy deployment of chiaroscuro stroking the flesh of the rippled physiques. The naked bodies on display are fashioned in two ways: they are the result of a process of self-fashioning through a physical augmentation of proportions via the body modification inherent to the act of building up musculature; and they are fashioned by the sexualizing gaze of the photographer who enhanced their appearance.

Moreover, the eroticization of the bodies under study is evident insofar as they are depicted in the act of clinging to each other: the feeling of intimacy is visually articulated, as well as affectively shared with the viewer, through tactility, i.e. via an embodied sensorial experience. However, if the object of the campaign is safe-sex, we are left to wonder how the safety caveat is illustrated in the images. Rather, the emphasized proximity of the naked bodies, their unbounded corporeal engagement, suggests a mode of relationality that is so intense and alluring that it does not require safety as a precondition for its instantiation; to the point that if these were real life scenes, we would most likely be prompted to infer that no prophylactic is being employed. The glamorized masculinity of these men, mirroring the physicality of models and athletes featured in the clothing campaigns authored by the same photographers, on one hand reflects the paradigms of gay corporeality of the time, on the other, paves the ground for a plethora of HIV prevention ads celebrating homoeroticism and conceived for a gay spectatorship.

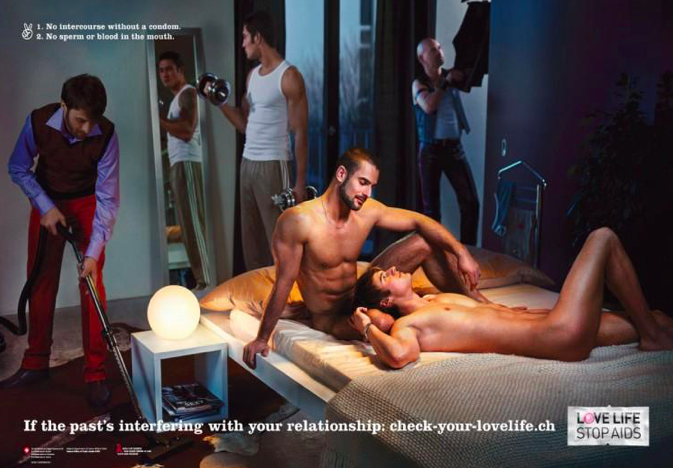

A more recent gay poster within the series of images from the “If The Past’s Interfering with Your Relationship: Check Your Love Life” prevention campaign produced in 2007 by the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health and shot by fashion photography duo Anoush Abrar & Aimée Hoving, is staged like a hip gay-targeted gym membership ad. The man sitting naked on the bed embodies the very standards of gay hyper-masculinity; behind him, a man lifting weights while staring at himself in the mirror is caught in an act of narcissistic self-fetishization; or, he may be glancing through the mirror at the toned back of the man seated, striving to identify with, and then sexually conquer him. However, if we consider the headline of the campaign as the hermeneutic key through which to deconstruct the social message of this collective portrait in the intentions of its creators, we could interpret the three men standing as the “past” “interfering” with the men on the bed. By virtue of a sexually active past, the two men, who are the object of the spectators’ attention and with whom they/we are expected to identify, are cryptically encouraged to get tested for HIV (“check your love life”).

Leaving aside the lack of transparency of its message and its being a hymn to stereotypical representations of gay men, in this picture, each body, in the same tiny bedroom, is involved in a styling act (cleaning, redesigning the flesh by building up muscles, picking clothes to signal belonging to the leather community) framing the object of the spectator's gaze: the chiseled bodies, illuminated by lamplight, of the two men who are about to, or who have just had, sex. If the three men behind the bed are supposed to represent their/our sexual past, nevertheless they look very much present. Being a past interfering with the present, they actually are present; and their presence is animated by a positionality of bodies that seem stuck in motion and likely to engage in group sex. At least to a queer eye, this is what this image may be winking at: all men, of whom the most conventionally attractive ones are naked, are in the same room preparing for sex, with or without precaution.

Amid this preparation, everyone in the picture seems emotionally “off.” There is no ongoing interaction. They are detached. Then, how is the past actually interfering with their present relationship according to the visual strategy of the picture? This sense of being frozen-in-feeling, affectively flat, is what queer theorist Lauren Berlant has called “recessive style” or “underperformed esthetic.”[7] Events that we would normally expect to be filled with tension may actually result in being perceived as suspended, uncertain: there is a stuckness-in-motion, an oscillation-in-potential, an overall underperformativity that renders what we are looking at hardly intelligible. As there is no actual participation, neither by the viewer’s body nor between the bodies in the photograph, in this event of performative suspension, emotional clarity is not provided and the image results in a celebration of withheld relationality and ambivalence. Thus, what could a gay man take from this picture beyond an invitation to seek sexual encounters with attractive others? Morality aside, is precaution necessary at all to accomplish this goal?

Rethinking the Margins of Health

The close relationship between HIV and gym culture has an additional medical explanation in the fact that HIV-infected men have frequently resorted to steroids in order to treat or prevent the body-wasting syndrome of AIDS. The discovery of steroids changed the traditional cultural standards of masculinity: their consumption allowed for the enlargement of the body in ways previously inconceivable. It is evident, then, to what extent the equation of muscles and health have marked gay men’s subjectivity since the 1980s. In the wake of the proliferation of hyper-masculine body images in the media from the 1980s, bodybuilding became widespread: the pervasive display of muscular bodies as both a symbol and imperative of health, along with the increasingly fast pace of capitalistic societies, led large constituencies of men to pursue a hardly attainable “healthy” look, often by resorting to steroids. Equating the muscular body with the healthy body is, therefore, extremely problematic. The paradox of steroids being employed to achieve healthy goals invalidates traditional ideas and discourses surrounding health. The hyper-masculine body has progressively come to identify the normative healthy body; health, in turn, appears to have lost its medical connotation and to have become a subjective aesthetic experience.

The “Play Smart” 2010 campaign by Visual AIDS, shot by fashion photographer Aaron Cobbett, consists of trading cards packaged with condoms picturing half-naked men in sport clothes; the ad reads “Get your Game On. Know Your Stats – Get Tested for HIV.” There is an obvious double entendre of the words “status” (HIV + or -) and “stats” (body measurements) in light of the muscularity of the men portrayed, who are well aware of their stats and, we are expected to assume, their serostatus. A glimpse suffices to recognize these images as highly erotic and ambiguous in terms of their encrypted social message. The man on the left, with very short shorts and a tank-top pulled behind the neck to show off the toned torso, is holding two tennis balls next to his crotch; the one in the middle holds a basketball with one hand and strokes himself from the inside of his trunks with the other while inviting us, through eyes and posture, to join him in the act; the man on the right is in his jock-strap down on one knee and staring at us while holding a soccer ball.

Based on the copy, we are encouraged to both measure our body stats, i.e. hitting the gym, and getting tested for HIV, thereby supposedly protecting others, with whom we engage in sexual encounters, should we turn out to be positive. In other words, this “know your status” campaign urges us to achieve the body appearance of the men displayed in order to have both significant stats to measure and a sufficiently erotic body with which to engage in sex, protected or not, and thereby have a motive for pursuing HIV testing.

The problematic nature of this ad lies, I believe, in the ambivalence arising, through the act of viewing, from the conflation of being enticed to conquer sexually and embody simultaneously a hyper-masculine physique, glamorized via clothing, musculature, and body makeup, which is presented as undifferentiatedly HIV negative or positive. It is as though it were saying: as long as you know your serostatus you can have these bodies; or: as long as you have this body your serostatus does not matter, but make sure you know it. Far from devaluing attempts to destigmatize HIV by representing it as invisible on the body surface, I am suggesting that the very sexualization, via the practice of glamorizing gay hyper-masculinity, of male bodies obfuscates the invitation to get tested by blurring, through a rhetoric of visual pleasure, the epistemologies of risk with an aesthetic of desirability. This might shift the viewer’s attention from the act of being summoned to pursue testing to the desire of being and being with these bodies, whether they are HIV negative or positive.

Unbounded Bodies, Unbounded Affect

What if the bodies featured in prevention ads were indistinguishable from those of a sex subculture bound by the glamorization and fetishization of the HIV virus?

Fashionable safe-sex ads depicting hyper-muscular bodies were being disseminated in the late 1990s also in relation to the introduction of anti-retroviral drugs in 1995, which brought about great benefits for HIV+ people; their gradually acquired wellbeing, often together with a newly achieved “healthy” appearance, were mobilized and leveraged in order to propel unrealistic images of beauty that began to unhinge the visible association of HIV with sickness. Mortalities were declining and the new medications were managing to render the virus undetectable. However, in the same timeframe in which the AIDS pandemic seemed to be tapering off, the discovery of protease inhibitors, the introduction of Viagra on the market, along with the emergence of online chatrooms and the circulation of crystal methamphetamine, prepared the ground for the surfacing of a willingness among gay men to engage in risky sex. The so-called bareback community was born.[8]

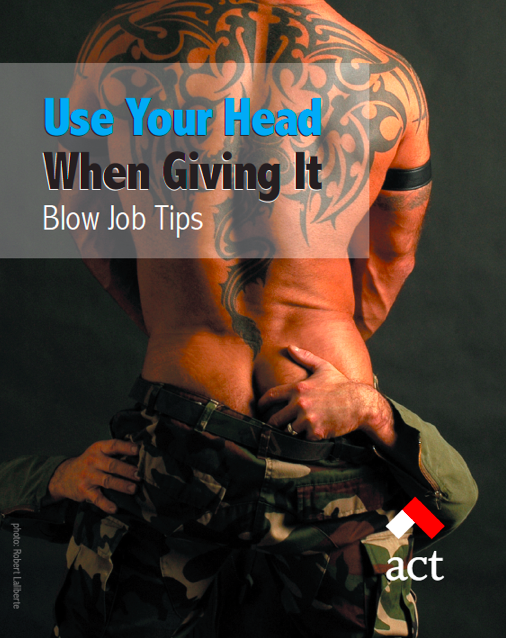

The term “barebacker,” evoking the image of the cowboy, which has historically informed gay erotic imagery, refers to gay men who deliberately relinquish prophylaxis during sex, often, in the case of "bug-chasers," with the intention of exposing themselves to the HIV virus. A bareback iconography is startlingly conjured in the bodies portrayed in the “AIDS Changes Everything: Play Safe – Get Tested – Seek Treatment” 2007 awareness campaign featuring International Mr. Leather Bo Ladashevska with his partner, photographed by Robert Laliberté and produced by the AIDS Committee of Durham Region, Ontario, as well as in the “Use Your Head When Giving It: Blow Job Tips” 2013 by the AIDS Committee of Toronto. Some might question why extensively tattooed and pierced hyper-muscular bodies parading sexual exuberance were chosen for HIV prevention ads. It would be interesting to know precisely to whom these images are supposed to be speaking. Also, what modes of longing and belonging could they foster? I tend to construe them as unintentionally trespassing the borders of figurative conventions, visually fostering identification with glamorized hyper-masculine bodies.

Furthermore, are the bodies in these ads supposed to index HIV positivity, negativity or neither? What I find problematic is that both inferences would be by any means misleading. I assume that according to the creative team that conceived the pictures, such muscular physiques unquestionably embodied health and thereby served the purpose of conveying an image to which HIV-negative men would or should aspire: this may trigger the dangerous illusion of equating good looks, and appearance in general, with health (in fact, HIV+ men can be in great physical shape while still carrying the virus, or, conversely, have a minimized viral load which makes them healthy de facto). In turn, if these bodies are meant to be associated with HIV+ individuals, then their eroticized visual representation may sketch an aura of sexual allure that elevates them to fetishizable objects for the viewer’s gaze: HIV+ bodies would, then, be represented as even more desirable than HIV- ones; this belies the obvious acknowledgement of serostatus failing to be a visible determinant in physical attractiveness. It is in this sense that I refer to the showcasing of aesthetically hard-to-attain bodies in prevention material as a possibly unintentional glamorization of HIV, which is a core principle in the philosophy of bug-chasing.

The bareback subculture is rooted in the ethos of hyper-masculinity originally embodied by the gay clone, whose aesthetic reappraisal, with peculiar upgrades, constitutes his iconic image. Buzzed haircuts, muscular physiques, tribal or biohazard tattoos, extended pierced nipples, leather or military accoutrements; in more extreme cases, for many bug-chasers, tattoos reading “poz” or “HIV+” are signifiers that provocatively mark a “positive identity” and proudly advertise the belonging to a community of sexual radicals. These tattoos and piercings are not mere visual signs: they become integral to their "corporeal schema,"[9] hence determining the comportment of their bodies in sexual interactions. In other words, they serve to symbolically ground the bodily experience of the world in the actual engagement with it. It seems to me that such a self-fashioning practice is the meticulous visual translation of a sex philosophy: stigma is converted into pride and sexual shame is resignified by transvaluating the abject into an object of identification.

The practice of engaging in unsafe sex pertains, not for all barebackers but certainly for most bug-chasers, to the broader enterprise of redefining kinship through HIV. The pathogen is reconceived as an object imbued with affective potential and seroconversion becomes the precondition for the establishment of a sense of belonging, which is felt and accomplished through the infringement of bodily and emotional boundaries. The abandonment of protection is, thus, readable as the breaking down of any barrier dividing the self from the other. It is a gesture that reframes the perceptive experience of risk: the rhetoric of vulnerability is subverted through its own eroticization. Bug-chasers reconceptualize intimacy as a radical experience which allows, through the flowing of positive bodily fluids, for the multiplication of corporeal connections with other subjects within a unified past-present-future. Normative temporality is dismantled in favor of a new queer hyper-extended, if not infinite, temporality that embraces life through joyfully deadly sex acts that resist normalizing ideas of health.

I suggest that barebacking could be construed as a form of embodied radical thinking whose disruptive potentiality consists in the articulation of a new relational ethics. The aesthetics of risk molds new forms of kinship that oppose the neo-capitalist, both hetero-normative and homo-normative, idea of “reproductive futurism”[10] and deconstruct the sanitized epistemologies of bodily practices. Today, while assimilationists tend to argue in favor of queer visibility, barebackers, by exposing themselves to risk, may be materializing new structures of desiring and feeling as well as instituting a new modality of homo-social bonding, hence proposing a counteracting lifestyle ontologically freed from social ties of monogamy and parenting: the aesthetics of barebacking does not subscribe to the tenets and values onto which prescriptive lives are culturally built and, instead, makes auspicious an ethics based on the freedom of bodily and psychic unboundedness.

Conclusion

This essay originates from research I have been developing after returning to my master’s thesis in fashion studies on the representations of queer masculinities in fashion photography. With anthropological curiosity I have been navigating queer worlds, intellectually flirting with radical ideas about sexuality and affect, with the purpose of making sense of the interweaving of self-fashioning and sexuality, which has always seemed to me uniquely articulated among gay subjectivities.

Through an analysis of a few case studies of HIV prevention advertisements that appeared across different geographical contexts between 1991 and 2013, my aim was to illustrate the depiction of glamorized hyper-masculine bodies as highly problematic in light of the troublesome perception of HIV stemming from it. I have posited several questions, which I have attempted to unpack without setting out to provide answers. The purpose of this essay has been, rather, to critically address and somewhat disentangle the convoluted matrix of representations of HIV in relation to hyper-masculinity by suspending judgement and offering alternative paths for reasoning with the images under study.

The sexual (and affective) practices I have ended up describing may open up groundbreaking possibilities for rethinking the borders of our embodied self beyond and against the normative box of theoretical tools with which we all have, to various degrees, scripted our lives. In doing that, we inevitably find ourselves facing several ethical conundrums which may not be easily resolved. The rationale of this article lies in an invitation to approach and unpack images critically by looking, feeling, and acting through them: that is a point of departure for elbowing through the mazy architectures of representations and finding our way out into an apprehension of the radical potentiality of our bodies, with or without dress.

Notes

[1] Stephen Seely, "How Do You Dress a Body without Organs? Affective Fashion and Nonhuman Becoming," Women's Studies Quarterly 41 (2013): 247-265.

[2] Shaun Cole, ‘Don’ We Now Our Gay Apparel’: Gay Men’s Dress in the Twentieth Century (Oxford: Berg, 2000), 93.

[3] Martin Levine, Gay Macho: The Life and Death of the Homosexual Clone (New York: NYU Press, 1998).

[4] Tim Edwards, Cultures of Masculinity (London: Routledge, 2006), 34.

[5] Daniel Harris, The Rise and Fall of Gay Culture (New York: Ballantine Books, 1997), 99.

[6] Marco Scalvini, “Glamorizing Sick Bodies: How Commercial Advertising Has Changed the Representation of HIV/AIDS,” Social Semiotics 20 (2010): 219-230.

[7] Lauren Berlant, “Structures of Unfeeling: ‘Mysterious Skin,’” International Journal for Politics, Culture and Society 28 (2015): 191-213.

[8] Tim Dean, Unlimited Intimacies: Reflections on the Subculture of Barebacking (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009).

[9] In Merleau-Ponty's phenomenology: forms of practical knowledge through which the body's agency makes itself manifest in the world. Maurice Merleau-Ponty, The Phenomenology of Perception (London: Routledge, 1962).

[10] Lee Edelman, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive (Durham: Duke University Press, 2004).

Uncited Bibliography:

Eugénie Shinkle, "Uneasy Bodies: Affect, Embodied Perception, and Contemporary Fashion Photography,” in Carnal Aesthetics: Transgressive Imagery and Feminist Politics, ed. M. Zarzycka et al. (London: I.B. Tauris, 2013).

Francesca Granata, Experimental Fashion: Performance, Art, Carnival and the Grotesque Body (New York: I.B. Tauris, 2016).

Jose Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: NYU Press, 2009).