Exhibition Review: Boro Textiles: Sustainable Aesthetics

Japan Society, New York, NY, March 6 - June 14, 2020

Figure 1. Installation view of Boro Textiles: Sustainable Aesthetics. Photograph by Alina Osokina.

Boro Textiles: Sustainable Aesthetics, curated by Yukie Kamiya and Tiffany Lambert, explored a textile practice that originated in the 19th and 20th centuries among peasants in the northern region of Japan where the cold climate made growing cotton difficult. Pieced together from scraps of used fabric, boro textiles were transformed into practical garments, such as coats, undershirts, trousers, socks, bags, and blankets. While simple in appearance, boro demonstrates human care, with warmth preserved in every stitch and patch layered over the generations. The creative exhibition design by Jing Liu’s and Florian Idenburg’s architecture firm SO-IL supported the emotionally powerful narrative and connected the humble objects to contemporary concerns. [1]

The Japan Society was founded in 1907 to cultivate cultural exchange and dynamic relationships between the people of the United States and Japan. [2] It is located in a quiet area of Manhattan near the United Nations on 47th Street and First Avenue. Upon entering the minimalistic entrance hall, visitors were greeted by a giant bouquet of blooming, pink branches and Teppei Kaneuji’s installation in the lobby pond. [3]

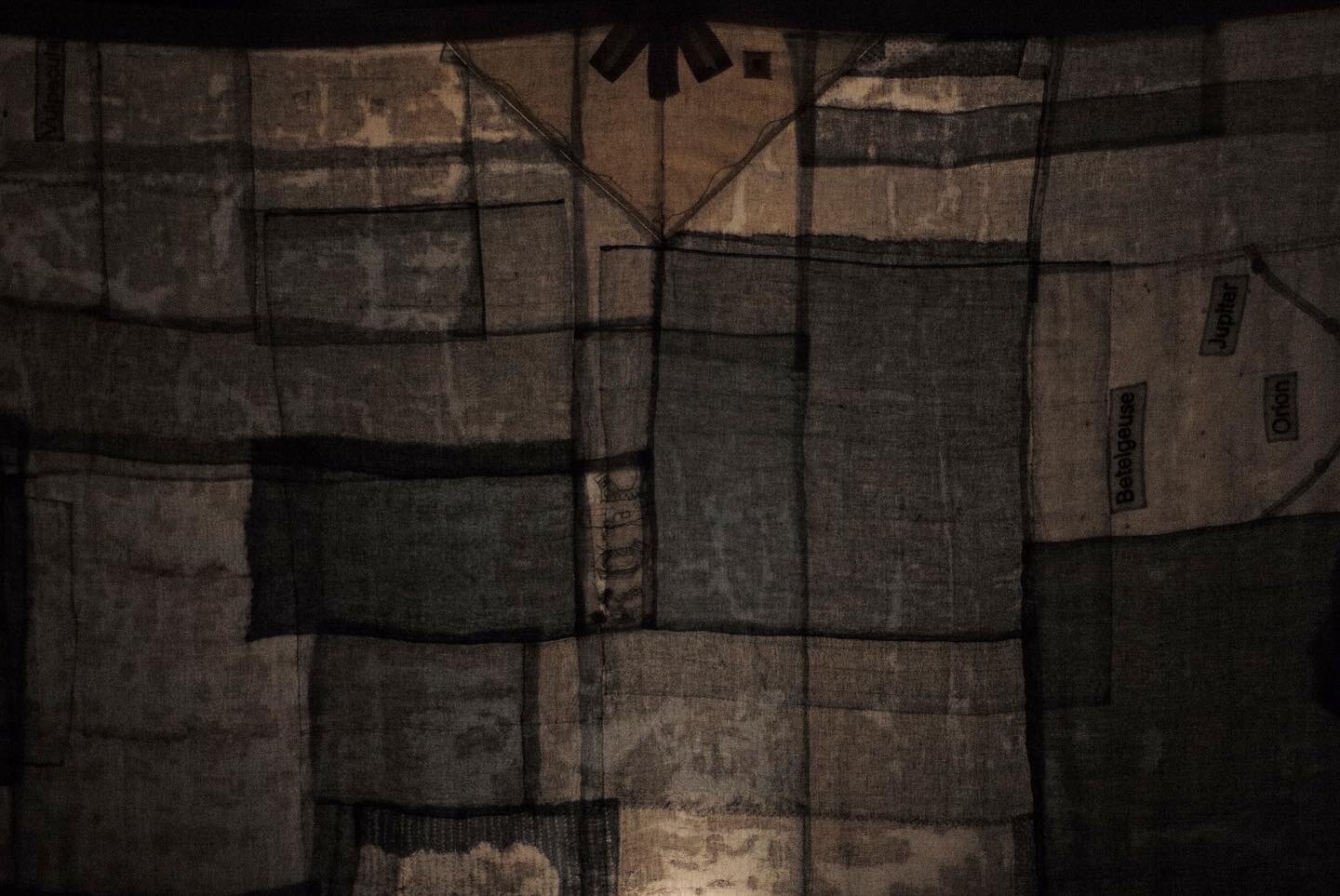

Boro Textiles was installed in the building’s dusky second floor galleries, outside of which was an introductory text that provided a thorough overview of the history that awaited inside. In this darkness, a subtle warm glow came from the tears, holes, and loose textile weaves of the thick robes (donja, tanzen), undershirts (asehajiki, hadaji), long kimono (nagagi), shirts (sakiori) and children’s clothing hanging in the air on barely visible mounts (Fig.1). Rings of transparent plastic provided support to the garment like a ribcage and the lamps were placed in the area of hearts. It created a quiet, mysterious feeling - sad, yet cozy and heartwarming, like the light of fireflies, the distant glow of windows in the dark, or enigmatic Obon festival lanterns. Like souls, these subtle yellow lights brought the garments to life perhaps more effectively than is possible with even the most naturalistic mannequins (Fig.2).

The curators allowed enough space around each object so that it was possible to intimately observe their textures and construction. Under the robes and shirts, pairs of shoes were placed on the clever stands with reflective surfaces so visitors could see the construction and condition of the soles and the reflection of the garments’ insides. The representation of men’s, women’s and children’s wear together added to the intimate, domestic and vulnerable nature of the story. At the end of the gallery pairs leggings known as mataware and tattsuke and women’s bloomers known as monpe, were hung in several rows (Fig.3). The displays were numbered and concise, and straightforward notes provided historical and technical facts on the quotidian hardships of the ordinary farmers and fishermen who wore these garments.

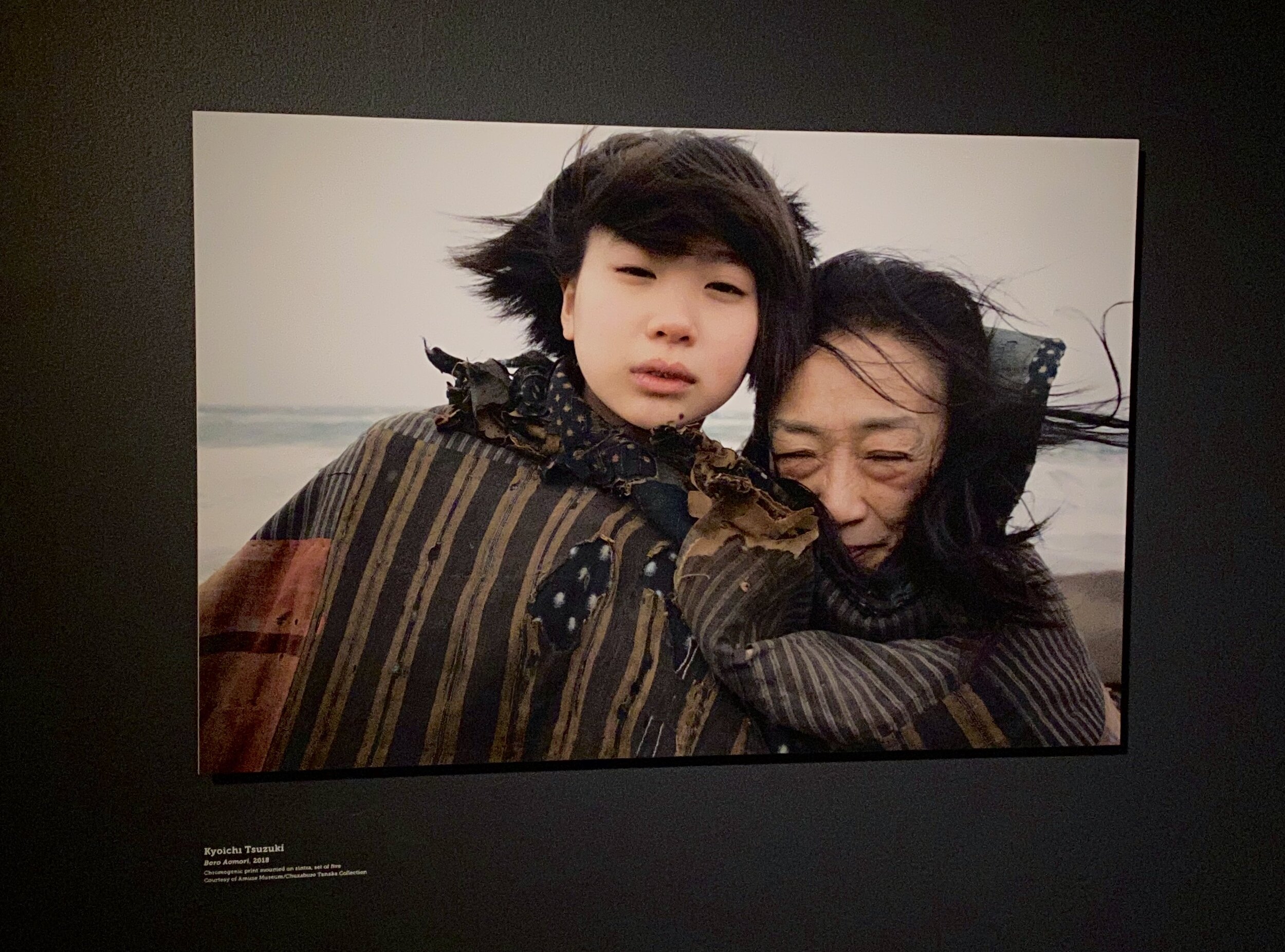

Instead of employing emotional, heartrending narration through the text, the severity of Tohoku’s northern climate and living conditions were demonstrated in the second gallery through the photographs of Kyoichi Tsuzuki. Throughout 2018, he documented the impoverished and rural areas where the boro garments were originally worn. These were artistic, documentary photos that vividly depicted the bitter social history behind the trendy buzz words, sustainability and boro. Tsuzuki’s characters stood alone wrapped in patchworked blankets in the cold wind or heavy snow with an austere landscape in the background. In other pictures, they were photographed in pairs clinging to each other and their ragged boro covers, their only sources of warmth (Fig.4). Along with Tsuzuki’s photographs, the second gallery accommodated a large display of boro accessories of various types, including bags, mittens and tab socks, arranged on a twelve-and-a-half-foot long table designed so that viewers could see their undersides (Fig.5). The reflective surface of Mylar that supported the objects recalled the cold, icy surfaces depicted in the adjacent photographs.

The third room with contemporary designs was even darker than the first gallery. The mood was slow, quiet, contemplative and still mysterious. A soft glow of mosquito net, Kaya, and the contemporary version of bodoko (padded mat) created a homey intimate feeling (Fig. 6). These objects were contrasted with commercial mannequins striking standard fashion poses that wore designs by Rei Kawakubo, Issey Miyake, and Yohji Yamamoto (Fig. 7 and 8). These high-fashion objects, as well as works by two contemporary textile artists, Susan Cianciolo and Christina Kim, were inspired by patchworked, deconstructed and repurposed aesthetics. To highlight this dialogue, they were juxtaposed with large boro blankets, some weighing upwards of 65 pounds, that hung from the ceiling. [4]

Over 50 archival pieces from the enormous personal collection of folklorist and cultural anthropologist Chuzaburo Tanaka (1933–2013), loaned from Amuse Museum, are exhibited in the United States for the first time. This exhibition was part of a year-long initiative Passing the Torch promoting the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo and focusing on their sustainability and recycling theme. [5] Boro Textiles: Sustainable Aesthetics at Japan Society was not the first exhibition featuring boro textiles. Indeed, the longstanding Japanese tradition of avoiding waste, appreciation of imperfection as in wabi-sabi and the ceramic art of kintsugi, are often celebrated in the museums around the world, and boro garments often make their appearance as an embodiment of these concepts. In 2013, for instance, Boro: The Fabric of Life was organized by Parsons Paris and showcased pieces from the private collection of New York-based gallerist Stephen Szczepanek. In 2014 the Boro: Threads of Life exhibition was organized at Somerset House, and in 2016 Shinichiro Ishibashi’s boro garments were displayed with a Jan Kath rug at Kyle & Kath gallery in New York. And these are only a few examples. However, these shows mostly focused on the design of the objects and hardly addressed historical and social aspects of boro textiles. By turn, this exhibition at the Japan Society can be distinguished from the previous shows by the touching exhibition design and the curators’ exploration of their impoverished sad origins.

The people of Tohoku who constantly mended their humble garments were not making works of art — they were making them as necessities to keep warm and stay alive during harsh winters. Boro Textiles: Sustainable Aesthetics did not only touch on the trendy topic of sustainability and emphasize the idea that textiles were and should be valued. It demonstrated fragility and transience of life reminding the guests to cherish the comfort they have today.

Notes

[1] “Boro Textiles: Sustainable Aesthetics.” Japan Society. https://www.japansociety.org/page/programs/gallery/boro-textiles (accessed April 25, 2020).

[2] “Mission Statement and Overview.” Japan Society. https://www.japansociety.org/page/about/overview (accessed April 25, 2020).

[3] “En/trance.” Japan Society. https://www.japansociety.org/page/programs/gallery/entrance (accessed April 25, 2020).

[4] Kat Barandy, “SO-IL Celebrates Beauty in Repair-work with Boro Textiles at Japan Society Gallery.” DesignBoom, March 15, 2020. https://www.designboom.com/art/so-il-boro-textiles-sustainable-aesthetics-japan-society-gallery-03-15-2020/ (accessed April 25, 2020).

[5] “Japan Society Gallery Presents Boro Textiles: Sustainable Aesthetics.” Japan Society. https://www.japansociety.org/page/about/press/boro-textiles-sustainable-aesthetics (accessed April 25, 2020).