Review: Femme Fatales: Strong Women in Fashion

Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, The Hague, Netherlands (November 17, 2018 - March 24, 2019)

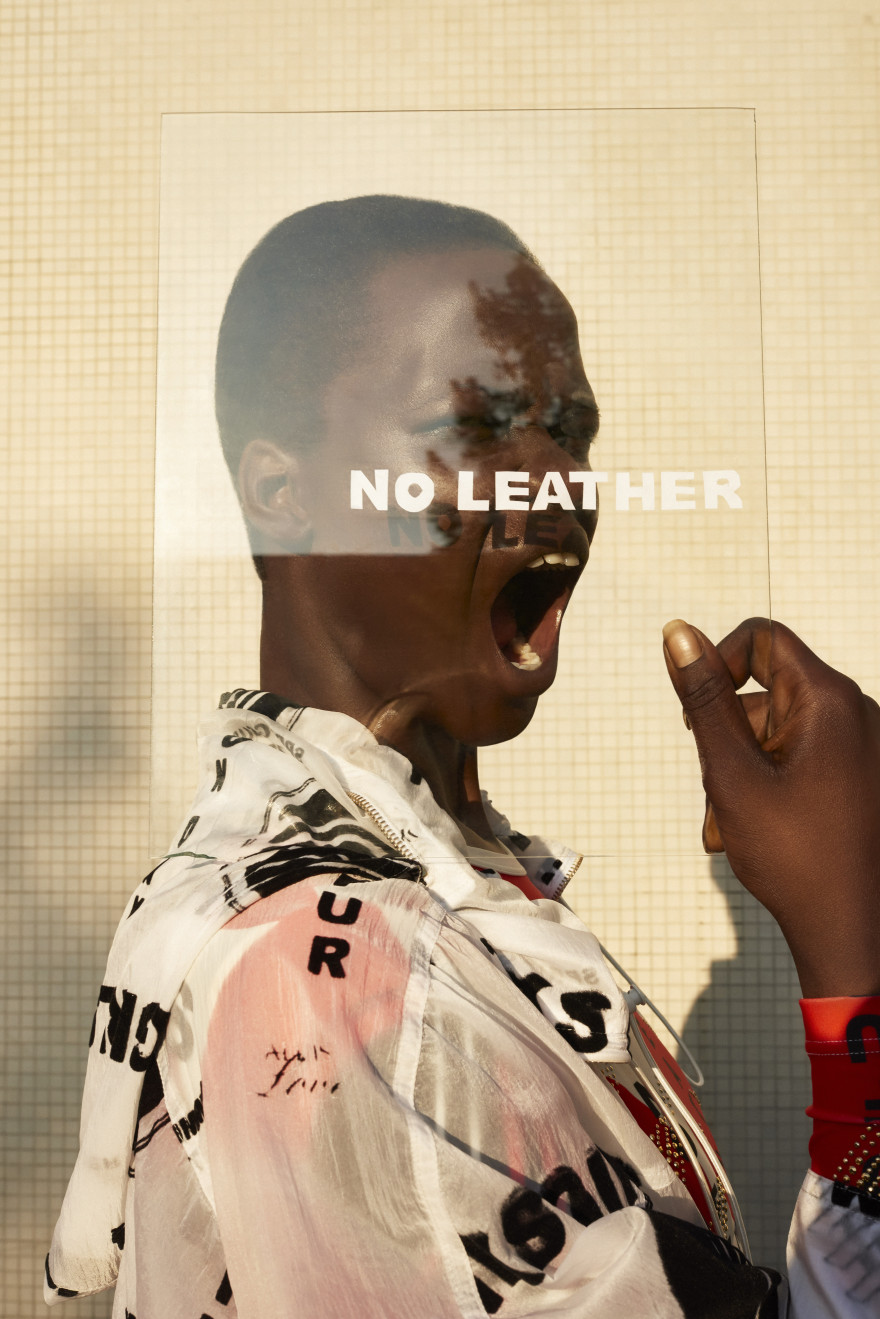

Stella McCartney, Spring 2017. Petrovsky & Ramone (photo), Maarten Spruyt (art direction) for Gemeentemuseum Den Haag. Courtesy Stella McCartney & the Gementeemuseum Den Haag.

Politics, feminism, innovation in research and technology, sustainability, and the environment are all significant subjects across contemporary society. Various ‘languages’ are chosen for expressing ideas and making statements about the time we live in, and fashion is among them. Fashion is a powerful medium that permits the display of narrative by both its producers and consumers, and can be used to study our society, reading the past and present to try to imagine the future.

But is there a difference between men and women in the use of fashion to communicate thoughts and express ideas? Is there diversion of self expression between genders? If so, has this gap always existed?

Gemeentemuseum Den Haag in the Netherlands has organized Femmes Fatales: Strong Women in Fashion, the first exhibition to focus exclusively on female designers, at a moment of increased female leadership at the helm of fashion houses in a business historically dominated by men.

The exhibition was inspired by Maria Grazia Chiuri’s first fashion show as Creative Director of Dior for Spring/Summer 2017 which featured T-shirts with slogans including Dio(R)evolution and We should all be feminists, aimed at participating in the social and political debates surrounding gender and power that had picked up steam in the months prior after the election of President Trump and the #MeToo movement. This show reflected a turning point in the history of feminism and its role in fashion, which the exhibit attempts to capture.

Femmes Fatales: Strong Women in Fashion examines the work of female couturières and designers since the seventeenth century, questioning if there are differences in the work itself or the designers’ vision of fashion when compared with that of their male counterparts. Themes are developed chronologically and presented visually through a reproduction of a rebellion, with banners spelling out protest messages.

The exhibition’s first section is titled A Woman´s Job?, a question that evokes the gendered differences in opportunity that characterized the fashion industry for centuries, due to the guild structure. Until the French Revolution, tailoring was exclusively a male profession, as were embroidery and corsetry. While women sewed wool or linen items and finishings for women’s wardrobes, undergarments, and children’s clothes, fine decorations for female court costumes were ultimately made by men. Women were called seamstresses, and were not paid as much as male tailors. Female artisans used a different method, more focused on the basis of the material than the cut, for example by folding or moulding the textile in order to achieve the right shape. This special attention to fabrics characterized the marchandes de modes, who were selling decorations for gowns, like bows and ribbons made from a different material than the gown itself.

The marchandes de modes introduced a concept of uniqueness and originality to fashionable dress that continued and crystallized into the next century. In the 19th century, the couturier gained another meaning, based more on creativity. In this realm, female pioneers could work at the same level as their male colleagues, as couturières, even though men were more recognized as artists and businessmen while women were still classified as simple seamstresses.

Female couturières represented in the section The Pioneers include Gabrielle Chanel, Jeanne Paquin and Jeanne Lanvin—their dresses displayed as examples of innovative designs applied to real life and inspired by emancipation movements and the suffragettes. These women successfully headed their own fashion houses because they were able to make their striking personalities and their femininity part of their professional identity. They understood that being women gave them an advantage in dressing the female body in an ideal way, as exemplified by Chanel’s jersey revolution, in which comfort was paramount.

“Is there a difference between men and women in the use of fashion to communicate thoughts and express ideas? Is there diversion of self expression between genders? ”

Individual designers are now the protagonists of the fashion scene. The exhibition dedicates a room to Elsa Schiaparelli, one of the largest personalities of her time in fashion, who flirted with the world of art, was among the first to give shape to abstract ideas, and articulated the idea of building architectural clothes like frames around bodies. Another room celebrates Madeleine Vionnet, whose research on materials, cut, and execution was intended to perfectly sculpt the female body’s geometric figures and lines.

Iris van Herpen, as we witness in the dedicated section Modern Handmade Work, uses 3D printing for the realization of movable and flexible garments, and experiments with new materials, sometimes created in a laboratory, with nature as inspiration. Herpen works with scientists, biologists, artists, and architects, and uses the computer for designing, part of a new definition of handicraft.

Following chronologically, we are introduced to the period after the Second World War, with pieces by Mary Quant, Sonia Rykiel and Barbara Hulanicki (Biba), all focused on femininity and comfort. In Revolutionary Mini Fashion, the Gemeentemuseum shows pieces from Quant, whose attributed invention of the miniskirt is still contested, but whose revolutionary infusion of youth culture into the fashion industry is not. Chanel herself participated in the women’s marches for the freedom to wear mini skirts, and since 1954 she supported the liberation the body, fighting against male businessmen like Christian Dior, whose conservative viewpoint was expressed through appearances intended to seduce men, also known as wife dressing, of which the New Look is the most famous.

Mary Katrantzou, collection summer 2018. Petrovsky & Ramone (photo), Maarten Spruyt (art direction) for Gemeentemuseum Den Haag. Courtesy Mary Katrantzou & Gementeemuseum Den Haag.

The 1970s were a watershed for female designers. Alongside the fashion for powerdressing (aggressive clothing that expressed a desire for respect and authority in a new corporate sphere), a new conception of wearable fashion compatible with the feminism of the moment found its place in the fashion industry. In the section Close to the body, the work of Diane von Fürstenberg appears, highlighting her wrap dresses, rich in femininity but also suitable for a life in business.

Single garments are celebrated in sections like The Power of a Good Coat, where Dutch designer Fong-Leng shows how beautiful and magnificent a person can feel wearing any one of her monumental dresses or coats.

T-shirts also became a great vehicle of expression in the eighties, when Katherine Hamnett wore a version with a message of protest while shaking hands with British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. As mentioned above, t-shirts have been used to make political statements ever since, including in the 2017 Dior collection.

Other political statements in the exhibition are the “pussy hats” designed by activist Kat Coyle and adapted by Angela Missoni for her Autumn 2017 collection as a protest against Donald Trump. Dresses designed by Phoebe Philo for Céline are presented in the section Cool, focusing on her explicit activism and campaigning for women’s rights, as well as her use of sustainable materials.

Designers Miuccia Prada, Isabel Marant, Clare Waight Keller, and Vivienne Westwood are also represented. Throughout her career, Westwood has remained socially engaged, fighting for a range of political and environmental causes such as climate change and the mass extinction of animal species. Her work is featured in an impressive array in the room Protest and commitment, where her punk style is enriched by a quote in giant letters reading Buy less, Choose well, Make it last.

The closing section at the Gemeentemuseum is a window to the future, with an overview of a few emerging female designers and their initiatives. This leaves the discussion open, even questioning if statements made through fashion are sometimes merely for marketing or trend-creation purposes.

In any case, the plurality of voices involved in the female fashion industry is investigated and celebrated in a project that unveils the peculiarities of women’s work. The show explores the attachment to wearability and accessibility, the role of craftsmanship, realism and the necessity to express a specific time and its social problems, the importance given to diversity, femininity and feelings felt by women dressing their own bodies. Indeed, the element of the body is crucial—and the fact that women are ready to use and experiment with it explains the title of the exhibition. This phenomenon is also evident in the textile-related material in the exhibit, because textiles are in direct contact with the body and need to respect its shapes and proportions. That, in essence, is female design.