Film Review: The Gospel According to André

One name echoed through the halls of Condé Nast College of Fashion & Design: André Leon Talley. He inspired my cohorts, who traveled from all over the world to the publisher’s fashion media and marketing school in London, and I to apply. We had trouble articulating why André resonated with each of our diverse national, racial, sexual, and economic backgrounds. Part of it was André’s seemingly ubiquitous presence in Vogue's history and as host of the Vogue Podcast. Part of it was something much more personal.

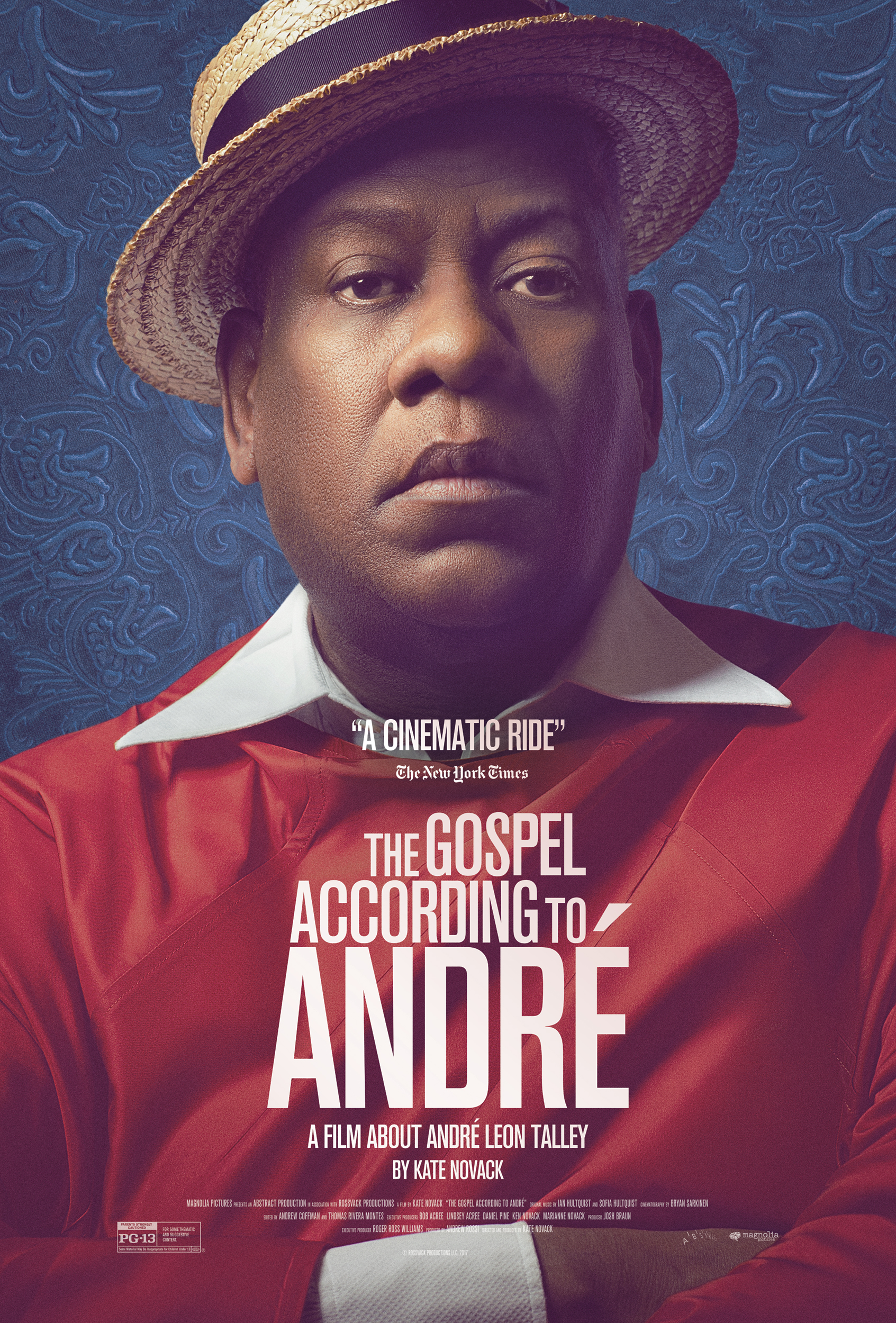

Director Kate Novack (Eat This New York) begins to help us understand André’s reach in the The Gospel According to André (2018), a documentary presented by Magnolia Pictures.

André’s position at the center of civil rights conflict, prejudice against gay men, and the technological revolution make his story that of the United States in the mid-to-late 20th Century. His portrait is juxtaposed with a secondary storyline in which André and those close to him speculate on the outcome of the 2016 presidential election.

Watching the film in 2018 with hindsight creates an uneasy frame for André’s story. This film is elevated beyond the limitations of many biographical documentaries because Novack creates a dialogue with her audience. The Gospel According to André is as much about us as it is an exploration of André’s character, using his life as a case study to understand how we reached larger social and political issues of today.

Books and classrooms acquaint us with larger-than-life Civil Rights-era figures and narratives of the 1950s and 1960s. Their stories are told through moments like Rosa Parks’s refusal to give up her bus seat to a white passenger and Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech (1963).

Acts of passive resistance that take place in private are just as important, however. In a moving scene of the film, Talley recalls a group of white boys at Duke University throwing rocks at him while he walked the campus. Later in the film that overt racism is compounded when he discusses being derided as “Queen Kong,” hate speech directed at him for being both black and gay. In both cases he employs the Christian ideal of “turning the other cheek,” the same idea that informed King and Parks. This nexus of activism and religious commitment is also where Talley discovered the power of fashion.

André grew up in North Carolina, a place where he remembers “going to church was the most important thing in life.” Black churches served as community gathering spaces for African Americans to be free from white surveillance. Clothing was used to celebrate individuality and the center aisle between pews became André’s first fashion runway.

One scene in the film that illustrates this link between political liberation and fashion showcases the inspiration that James Brown, the Godfather of Soul, had on André. Talley succinctly defines his ethos towards pacifism by saying, “You don’t get up and say, ‘Look, I’m black and I’m proud.’ You just do it.” He moves one step past the 1968 anthem that made Brown a Civil Rights icon, suggesting that fashion was an expression of pride that could define blackness on its own terms. André’s friend Will.i.am of the Black Eyed Peas crystalizes André’s status within the lineage of black leaders by calling him “The Nelson Mandela of couture. The Kofi Annan of what you got on.”

“André declares, “You can be aristocratic without being born into an aristocratic family.””

André’s belief in fashion as a transformative experience led him to a passion for Vogue magazine. Its pages exposed him to the aspirational world of couture, education, and high culture. Speaking to his interest, André declares, “You can be aristocratic without being born into an aristocratic family.”

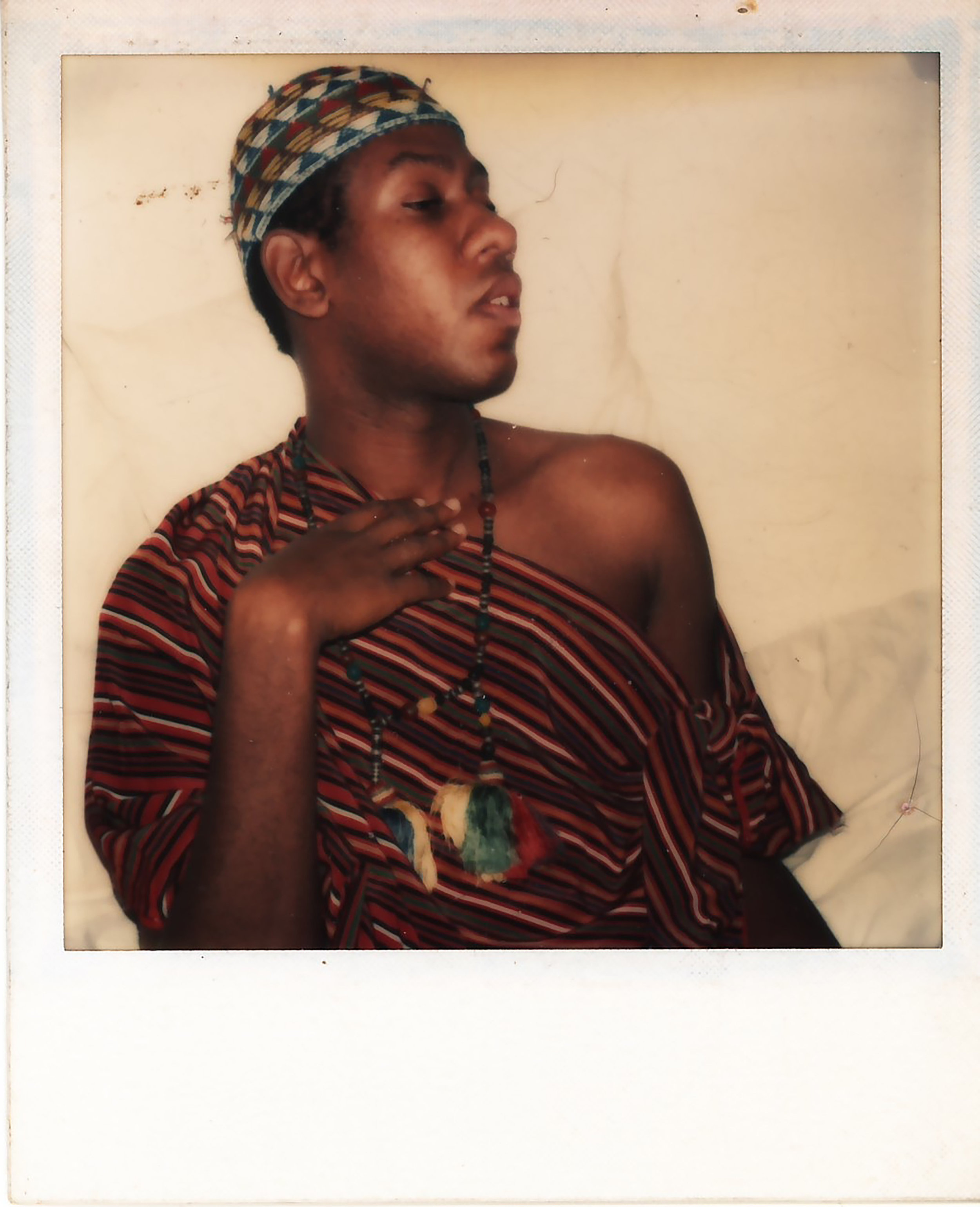

After pursuing an Ivy League graduate degree in French Studies from Brown University, he spent the 1970s through the 1990s landing jobs reporting for Women’s Wear Daily (WWD), assisting legendary Vogue editor-in-chief Diana Vreeland in her new role working for the Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and as both American Vogue’s Fashion News Director and Creative Director. This was an interesting moment in United States fashion history, when fashion was becoming more linked with Hollywood. André became a celebrity in his own right, hanging out with the likes of Andy Warhol, dancing the night away at Studio 54, and covering fashion weeks in Paris.

The Gospel According to André avoids glorifying its subject, despite this glitz and glamour. Novack is careful to portray the weight loss struggles intensified by André’s lifestyle. Critics of the film might argue that it’s difficult to convey empathy for such a privileged man. But it’s hard to avoid rooting for him when we see how devoted his friends and extended family are to his well-being. Anna Wintour, who, along with designer Oscar de la Renta, once staged an infamous intervention concerning André’s weight, reporter Tamron Hall, designers Tom Ford and Marc Jacobs, and other famous faces support André as he attends therapy sessions to better his eating habits. These somber scenes are a stark contrast to the playful take on André’s health in R.J. Cutler’s The September Issue (2009).

André’s unrelenting commitment to individuality and self expression holds the film together. It illustrates the most actualized depiction of style as defined by Quentin Crisp. Style, according to Crisp, is about full embodiment and presentation, rather than image. Image lends itself to posing, but true style is authentic. There are few people more authentic than André Leon Talley. Even when he witnesses the election of Donald Trump toward the film’s end, André is not deterred by the shock. He fights for justice just by being himself and spreading positivity through fashion, using the same language of moments he learned from biblical teachings and civil rights leaders. In a clip from 2017 Met Gala, André crystalizes his quiet hope for a future that builds on struggles of the past. Commenting on P.Diddy’s Rick Owens-designed pinstripe cape, André quips, “You’re giving us a futuristic James Brown moment.”

After watching The Gospel According to André, I realize why his name rang through the halls of Condé Nast College. He inspired my cohort to create genuine communities through self actualization the same way he inspires community among those he loves. How can he help you do the same? Find out when you see the film while it’s still in theaters now or when it hits digital platforms later this year.