Exhibition Review: Margiela the Hermes Years

Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, March 22 - September 2, 2018

Margiela, The Hermès Years celebrates Martin Margiela’s contribution to the French fashion house from 1997 to 2003. Originally exhibited last year at ModeMuseum, Antwerp, the exhibition’s entrance into a French institution adapts it to convey Margiela’s mark on the identity of French fashion. The exhibition, through 120 thematically-organized silhouettes, explores the themes of Margiela’s creations for Maison Martin Margiela (MMM) and how these were translated for Hermès women’s ready-to-wear. It argues that a singular DNA weaves its way through these two branches of Margiela’s creative career, reconciling the apparent disjuncture between Margiela’s identity as a rebel against the fashion system and a designer for one of French fashion’s most patrimonial houses.

Previously I wrote in my review of Margiela/Galliera 1989-2009, which opened three weeks earlier, that the idea of two Parisian museums having concurrent exhibitions on the same living designer is awkward and perplexing. Since, I’ve learnt from Laurent Cota, curator at Palais Galliera, that there was no communication between the teams of both museums, and that the only common thread was Margiela’s hand as artistic director in both exhibitions. I was therefore pleasantly surprised with the way the exhibitions seemed to create a dialogue with each other. In a way, Galliera’s exhibition opened the question of Margiela’s seemingly contradictory roles for MMM and Hermès. This contradiction was emphasized when it mentioned how the press had labelled Margiela as a ‘minimalist’ designer – to his disapproval – and how this paradoxically led to his oeuvre at Hermès. MAD’s exhibition then seemed to attempt to answer this by reconciling the designer’s identities of Belgian avant-gardist and French ready-to-wear designer.

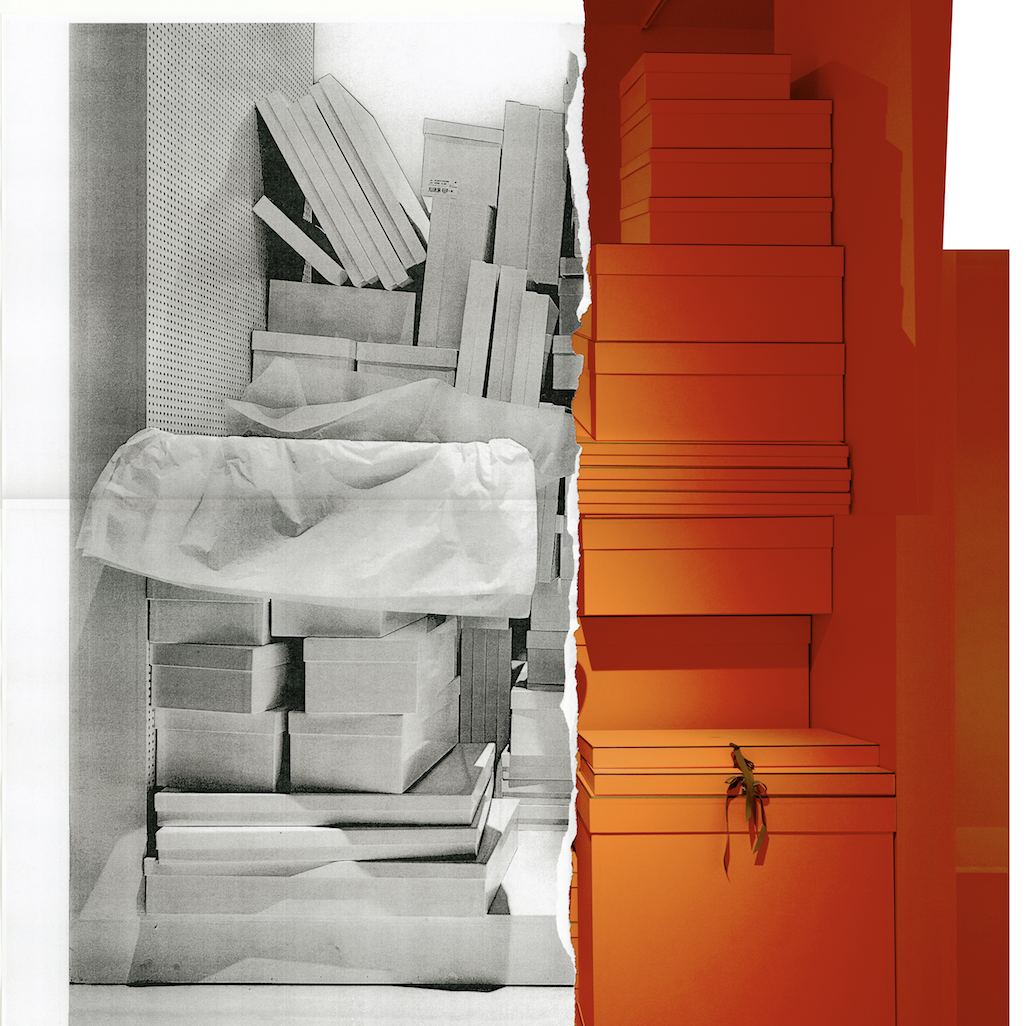

Entering the exhibition, I was immediately greeted by this perceived opposition through the floor-to-ceiling color blocking. Suzy Menkes’ analogy of “Hospital-coat meets sunset orange” [1] quite accurately describes the scenography that guides the dialogue between what was ‘MMM’ and what was ‘Margiela for Hermès.’ The orange-white symbolism serves as a running theme throughout the exhibition to literally demonstrate how Margiela’s initial concepts for MMM are translated into more conventionally wearable garments that speak the Hermès code of timeless luxury on the other side of the line. One could even argue that it suggests the usage of his own house’s collection as a conceptual study collection for his Hermès creations. Moreover, the color blocking lent coherence and continuity to MMM’s different pieces as the white paint would guide the visitor’s eyes across different ends of the room so as to connect them thematically and aesthetically.

The space, designed by Bob Verhelst, has spacious corridors, clean walls, and straight lines, The MMM garments are contextualized in a very different manner from the Hermès pieces, the former being embedded in elements that evoke deconstruction and transition. For example, a diversity of display techniques such as Stockman dummies, hangers, mannequins in varying states of hairdos, and the use of non-garment objects like lighting stands you would find on photo shoots and roughly painted repurposed furniture situate the MMM garments within MMM’s concept-laden avant-garde approach, often called deconstruction. These variations are juxtaposed against the standardized display of the Hermès pieces on identical, sample-sized mannequins throughout the exhibition. In this way, the dialogue portrays the MMM pieces as the ‘backstage’ of the construction of the Hermès pieces, lending intellectual validity to the Hermès pieces, which are presented like refined, more traditionally wearable variations of the MMM pieces.

“It struck me that it might have been more ‘Margiela-esque’ for the models’ faces to be veiled, for anonymity’s sake, and for their gestures and posture to bring life to garment.”

While the scenography situating the MMM pieces was more elaborate and spectacular, the Hermès pieces were situated in a somewhat no-frills environment. This worked to evoke a sense of humility, elevating the bigger ideas of Margiela as designer rather than the reverence of Hermès as fashion house. It seemed that the Hermès garments acknowledged their own commercialization in the face of the less straightforward, more avant-garde MMM pieces, thus attributing their symbolic capital to the intellectual input of Margiela.

Tackling the challenge of the bodiless garments and the representation of the body, this exhibition managed to overcome this stasis through the use of life-size videos on screens beside the Hermès garments. These depicted models wearing the garments and demonstrating the different ways the garments could function. These models, as per the Margiela ethos of inclusivity, ranged across ages and races and exuded a certain mature serenity aligned with the Hermès brand, thereby providing further socio-cultural context for the garments. It struck me that it might have been more ‘Margiela-esque’ for the models’ faces to be veiled, for anonymity’s sake, and for their gestures and posture to bring life to garment.

Other smaller video screens recalled past MMM shows that brought the static physical garments to life and conveyed Margiela’s original vision. On top of this, the aura of the garments was furthered through the sounds of the fashion shows that drifted through the exhibition space, creating a multi-sensory immersion into the world of Margiela. These grainy videos contrasted with the high-definition Hermès videos, echoing the construction-refinement dialectic earlier mentioned. Both types of videos conveyed the world of the garments in different performative ways, adhereing to what Marco Pecorari would call the “liveness of fashion.” On the use of performance as a curatorial act, Pecorari says that the “body as stage” can communicate “fashion in action” moving beyond the material to the immaterial. It conveys “the world around garments and their sensorial, lively contexts” and marks a shift “from a static vision of fashion to a performative dynamism to push and reflect the ‘liveness’ of fashion.” [2] In this way, the videos and overhead sounds successfully aided the visitor’s experience of these otherwise static and untouchable garments.

Yet, the use of the life-size videos resembled the merchandising practices you would find on fast fashion e-commerce sites like ASOS.com. This blurred the line between the art space and the commercial, making it easy to argue that the exhibition leaned towards selling the Hermès brand. But this would be a reductive reading. Rather, the exhibition seemed to acknowledge this risk of commercialization, especially since the same institution had just presented the blockbuster Christian Dior, couturier du rave show, and took care to pay homage to Margiela’s innovations in an intellectual manner through succinct wall texts and scenographic devices. For example, the duvet coat was spread out on a wall, and a video of the coat being ‘dressed up’ like a bed spread was projected on it. On the table in front of this installation, the newspaper spread of photographer Bill Cunningham’s street style coverage of the coat for The New York Times was presented. This multi-media approach and the drawing on fashion media to give context to the coat expanded the French-Belgian conversation underlying this exhibition to address Margiela’s impact in New York City and the American fashion media.

The final two silhouettes, a MMM evening dress repurposed from three old wedding dresses paired with black wool pants, and a black Hermès dress, were displayed on identical mannequins back to back, on a raised circular platform. In the MoMu exhibition, these were presented side by side. The repositioning of the mannequins, the raised platform, and the circularity of view pedastalize the collaboration with an aura of artistic productivity. The visitor walks around the display, understanding how this unlikely partnership has been fruitful to fashion creation and exits the exhibition, through orange doors, with a positive sense of history having been made. In addition, the mirrors lining the walls created an illusion of expansiveness and drove home the point that, ‘the possibilities are endless.’

While these factors worked to substantiate the artistic profitability of this collaboration, it was addressed largely from a designer-brand collaboration perspective, when the underlying significance lay very much in the Belgian contribution to French fashion. The exhibition in Belgium on a Belgian designer’s contribution to a French fashion house would have conveyed a different message when presented in a French institution because each, owing faithfulness to their respective museum missions, would implicitly aim to bolster their own national identities. Perhaps in a museum built on a history of promoting French innovation, it would be problematic to address this transnational dialectic beyond merely stating that Margiela is Belgian and that he graduated from the Royal Academy of Arts in Antwerp. Dwelling on this relation risks collapsing French fashion’s aura of Frenchness. Yet, this exhibition seemed to have been the perfect grounds on which to demystify the myth of national boundaries when it comes to fashion production. With a designer and a brand so steeped in their respective nationalisms, it would have leant greater authenticity and analytical vivacity to the exhibition to further interrogate the arbitrary assignation and maintenance of borders within the fashion system.

Notes

[1] Menkes, Suzy. "Preface." In Margiela: The Hermès Years, by Kaat Debo, Sarah Mower, and Rebecca Arnold, 7. Lannoo Publishers, 2017.

[2] Marco Pecorari, "The Liveness of Fashion: Performance as a Curatorial Practice" in Fashion Curating. Understanding Fashion Through the Exhibition, edited by Luca Marchetti, 227-232 (Geneve: HEAD Geneve Publisher, 2016).