Discussing Beauty with Kathy Peiss

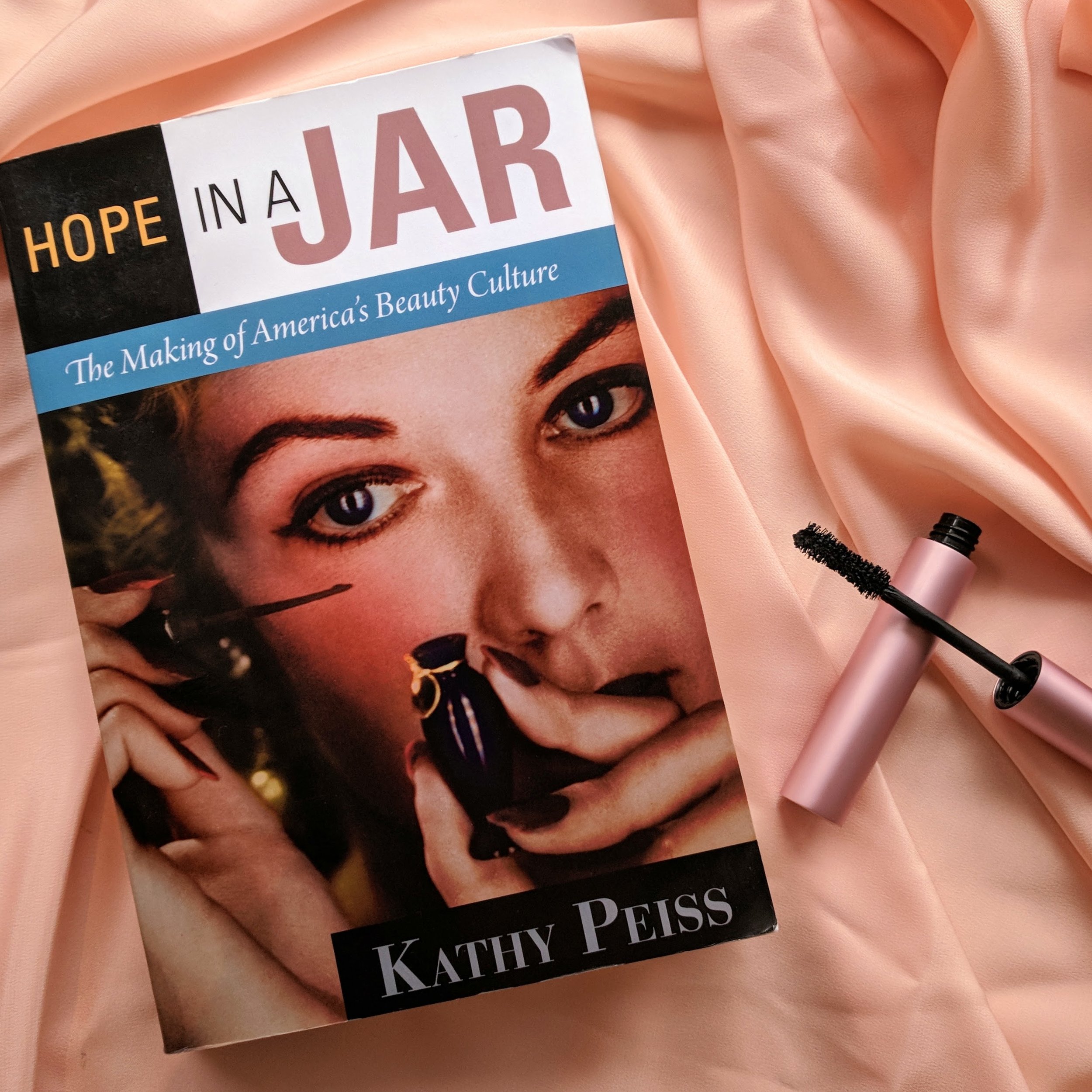

When Kathy Peiss published Hope in a Jar: The Making of America's Beauty Culture in 1998, she was in the midst of a feminist debate. The “beauty myth” — an eternal industry hot topic regarding the direct relationship between a woman’s success and pressure to adhere to societal standards of attractiveness — has long been an area of focus for Peiss, who is also the Roy F. and Jeannette P. Nichols Professor of American History at the University of Pennsylvania. Sharing Peiss’s interests in gender, sexuality, and cultural history, seven second-year students in NYU’s Costume Studies Master’s program conceptualized and curated an exhibition titled The Eye of the Beholder: Decade-Defining Lids, Lashes, & Brows. Running from January 13–February 2, 2018 at 80WSE gallery, the show examines the history of eye makeup in America from the 1900s to the present day. Ahead of her keynote speech at The Eye of the Beholder symposium on January 28th, Peiss spoke to co-curator Stephanie Sporn about eye cosmetics, women’s role in shaping beauty culture, and how the industry has evolved over the last century.

SS: What do you think makeup does that fashion does not?

KP: Because makeup is attached to the face, which is so central to the projection of identity, there is a belief that makeup is more essential or more grounded in who a woman is. Fashion is perceived as far more changeable. It reflects trends and styles that can change moment to moment.

The title of your symposium talk is “The Problem with Eye Makeup.” Without giving too much away, what do you believe is the problem?

At least in terms of the cosmetics industry, eye makeup was actually the hardest kind of makeup to sell. It had the slowest adoption rate of all the major forms of color cosmetics, and so I will discuss why that would be. What is interesting about the eyes is the element of artifice — it’s hard to make them look natural. You can use eyeliner in a way that mostly blends in, you can use shadowing, but when it comes to color, eye makeup conveys something that seems more artificial than reddening your lips or brushing on blush.

In Hope in a Jar, you wrote, “The public debate over cosmetics today veers noisily between the poles of victimization and self-invention, between the prison of beauty and the play of makeup.” Which angle do you find is more predominant for American women?

Women tend to believe in makeup not being a prison, but if you step back into a cultural analysis, you might come to a different conclusion. I think that the idea of being makeupless is a very hard one for most American women. My book is really about the moment at which makeup takes off, and how it was deeply connected to ideas of selfhood, modernity, and women’s freedom. But now, nearly 100 years later, you have to ask: what were the consequences of makeup, and is that in fact the case?

Can you speak to how the idea of makeup as transformative is a quintessentially American ideal?

At the point that makeup became popularized, there were many ways in which women were entering into a modern culture. Something about the sociability of working in factories and department stores, as opposed to the home, was really meaningful to women. Their leisure activities — dancing, movies, theater — also gave them this sense that their lives were going to be very different in the 20th century. Cosmetics were often seen as signs of immorality, but these young women rejected that. They saw makeup as something to embrace, a mark of a new, modern self.

Beyond their growing independence as consumers, how have women shaped the beauty industry?

Women, like Helena Rubinstein, Elizabeth Arden, and many others, have been incredibly important as entrepreneurs. The beauty business was considered disreputable, but it was women who were excluded from other business opportunities who could then claim, “Well as women, we understand each other.” The idea of women speaking to each other through consumer products was very new and important.

How do you think the cosmetics industry has progressed during the last 100 years?

The products have generally become safer. That change began taking place in the 1930s when some regulation of cosmetics developed. In recent decades, the turn to a kind of truer science of cosmetics has somewhat lessened the gap between the promise of a product’s claims and the reality of its results. The marketing of cosmetics to women of color is extremely important. This began early in the 20th century, but the real attention to the full range of skin tones happened later. A lot of the effort came from pioneering African American women, and just recently we saw this again with the Fenty Beauty phenomenon.

Do you think messaging around beauty products has changed?

There are continuous themes: there’s the health pitch, the youth pitch, the glamour pitch how those look in different time periods and how they are shaped by social context does change. In the World War II period, women were called upon to look beautiful as a morale booster. In the 1960s, teen marketing led to a very young kind of glamour. Over the 20th century, there is greater sexualization of models and cosmetics, although you can already see it back in the 1920s. By the end of the century, there is a proliferation of different aesthetics, palettes, and market niches.

In your opinion, what does the beauty industry still need to work on?

The beauty industry has always advertised in terms of aspirational pitches, and that has often led to truly impossible and harmful beauty ideals: the perfect body, the perfect face, the perfect hair. That cult of perfection is an unhelpful message to send, especially to young women, but also older women. There’s a real impetus toward a conventional view of beauty. Even if it may be multi-racial or various body types, there is a way of conventionalizing what beauty means and looks like. I think the industry could do better and pitch products using more ordinary, relatable people in their advertising.

A version of this interview originally appeared on EyeoftheBeholderNYU.com.