Stitching Together: What can Female Networking Groups of the Renaissance Teach Us About the Power of Making Clothes Together?

Giovanni Battista Moroni, The Tailor, 1565 - 70, oil on canvas. London: National Gallery. (Image Credit: National Gallery, London)

Prick. Pounce. Cut. Thread. Stitch. Sewing is a methodical and highly skilled practice that has been passed down from generation to generation. Hand-sewing is a craft that demands time and attention to detail, but it also requires learning from other skilled people to improve one’s ability. Because of this fact, sewing has a long tradition as a social activity comprising collaboration, sharing of ideas, and partnerships. And it is these aspects of sewing that were very much alive in 16th century Italy when women forged female networking groups to learn how to embroider, stitch, and make clothes together.

For women in Renaissance Italy, needlework was a very important practice; it was the peak of virtue in household responsibilities, even more so than other activities such as singing, dancing, and music. [1] However, when thinking of sewing in Renaissance Italy, it has so often been the male tailor who acts as the poster boy for this craft. This is perhaps, for the most part, thanks to Giovanni Battista Moroni’s painting The Tailor. The portrait shows the tailor as he stands at his workspace, looking out at the viewer, interrupted from his work, holding a pair of fabric scissors in one hand and black cloth in the other. Moroni’s painting epitomizes the masculine role of the tailor in Renaissance Italy and has been the starting point for much discussion on the crucial role of the maker, indicating the high value placed on dress, clothing, and craftsmanship in the Italian Renaissance. We do not know the name of The Tailor but we can assume that he was what was called a sarto, a master tailor; he would only have been hired to cut and stitch the most important clothing for the ruling elite. We do know that there were some female tailors known as sarte tailoring garments in the guilds in early Renaissance Florence, but curiously these roles were given to women less and less frequently throughout the 15th century. [2] Although women were marginalized from the masculine craft of tailoring, seamstresses had the responsibility of making linen smocks, shirts, and ruffs. [3] And as women were excluded from the guilds of the time, textile decoration and needlework were done at home, the craft becoming an important aspect of women’s daily lives.

In the Renaissance home, women sewed a whole range of textiles and found ways of expressing themselves through sewing. These textiles often included names, initials, and family mottos. [4] Women’s needlework mostly concerned family linens and household textiles, including towels, sheets, pillow slips, and in some cases in upper-class households, ornamental wall hangings. These textiles provided an opportunity to contribute to the representation of the family to the outside world from their private domain. There was a certain hierarchical structure among women when it came to arranging the supply and sewing of household textiles. Usually, wives and mothers of the household were in direct communication with servants in the home—young, unmarried women or nuns working from convents—to arrange the production of the household linens. This was an area of textiles in the Italian Renaissance that was not professionalized by a guild but remained informal and relied on networking groups of women; it was also an activity in which women on all social levels participated. [5]

Lorenzo Lotto, Portrait of a Woman inspired by Lucretia, 1530, oil on canvas. London: National Gallery. (Image Credit: National Gallery, London)

The most common item made by women at home was the embroidered linen shirt; an undergarment worn under every costume in Renaissance Italy, it was a staple of home production. Linen was available across all social levels and the linen shirt was worn by all. It was not easy to make; a shirt would have been an achievement and a labor of love. When worn, the only visible parts of the shirt were the neckline and the wrists, though in some fashions, “slashes” were made in the sleeve to showcase more of the linen shirt; the women’s handiwork of the shirt would peep through the overgarments that would have certainly been made by male tailors. This fashion can be seen in a painting by Lorenzo Lotto, Portrait of a Woman inspired by Lucretia.

When delving into the history of Early Modern fashion, it has become common practice to discuss women in fashion through portraiture, semantically decoding their dress and considering them as passive subjects. However, I seek to look at dress methodologically, adopting approaches to the history of fashion that have been exemplified by research groups such as Refashioning the Renaissance, led by Paula Hothi. By considering the materiality and sensory experience of making clothes instead of the remote practice of looking at archival objects or paintings, it is possible to uncover lesser-known and fascinating histories about the production of textiles by everyday women in the Renaissance. I conducted a research project with the supervision of Dr. Flora Dennis to research the embroidered linen shirt, understanding the techniques that would have been used at the time and exploring how women made these linen shirts for the men in their lives to wear in public within female networking groups operating in the private, domestic realm.

The tools used to make the shirt by women at home included needles, pins, and thimbles, much like today’s tools used for sewing. [6] A title page from a printed book on textile by Domenico de Sera from the 16th century paints a picture of what this experience would have felt like. It depicts a woman deep in concentration with her sewing work on her lap as well as a woman working on a loom while another woman stitches with a hand needle as she sits with a basket full of sewing equipment. While embroidering linen myself, I think of the many women that have contributed to this practice before me. Sewing is an experience: the feeling of the weight of fabric and the fine feeling of silk thread between my fingers; the sounds of the needle piercing the fabric; the satisfaction of completing a complicated stitch, and the continuous rhythm of sewing can surely not be too distant from what it would have felt like for 16th century women to sew. I have the women most close to me in my life to thank for my ability to sew, as did women of the Italian Renaissance.

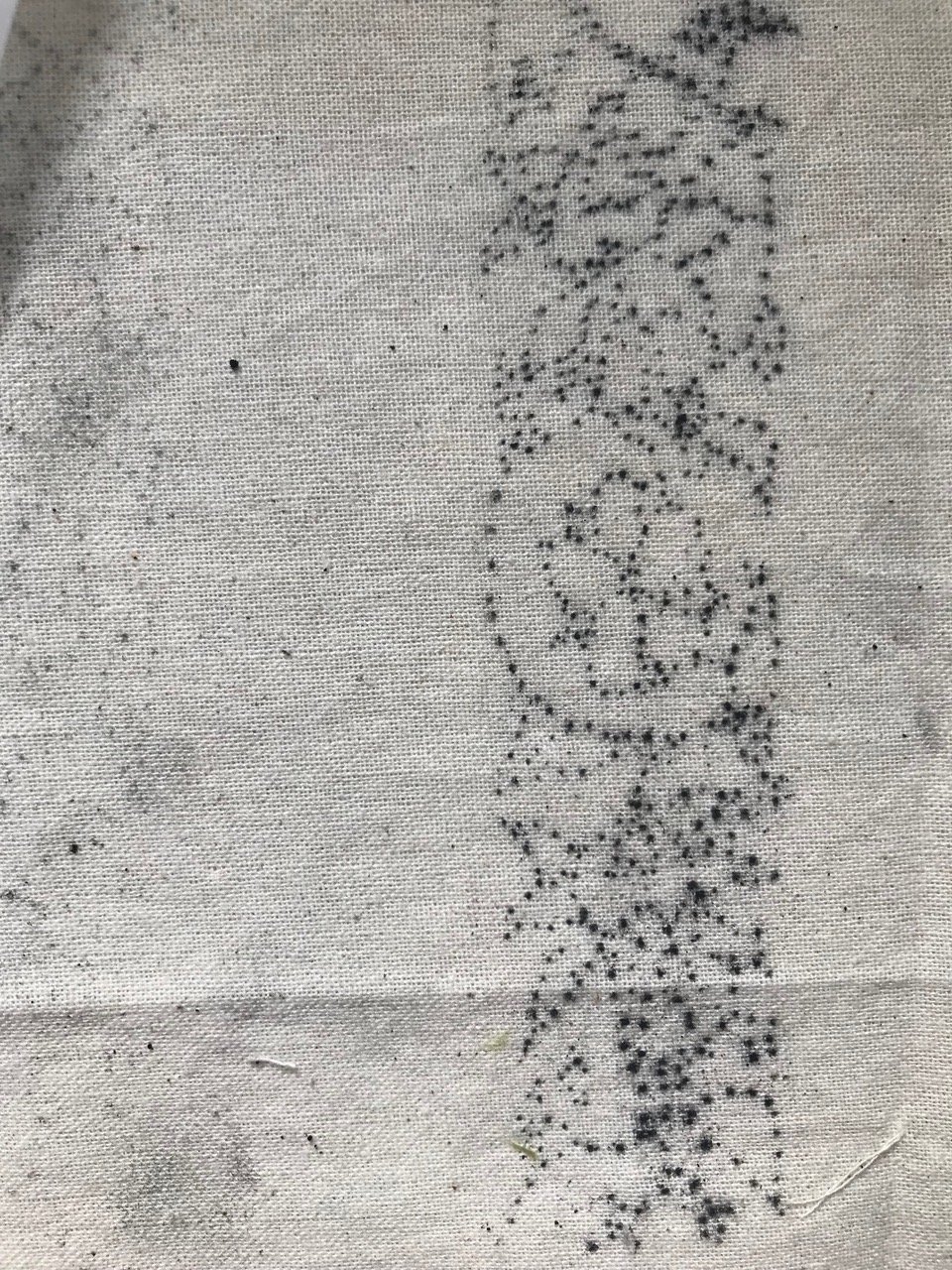

In a pattern book dedicated to needlework for ladies, Giovanni Ostaus’s The True Perfection of Design from 1567, a plate showcases Lucretia of the Romans with her daughters as she instructs them to conduct their needlework. [7] This printed book showcases the role of the matron as leading her students and teaching them how to sew. This reflects how crucial the transmission of this knowledge was from older generations of women to younger. Needlework was a craft that gave women in the 16th century the opportunity to exert their virtuosity. The history of women’s knowledge of sewing and sewing together was also commonly found in convents. Young women from upper class families would spend most of their day dedicated to learning and developing their embroidery skills and girls from impoverished families in the convents were taught to sew by female superiors. [8] Beyond family relationships, inherited knowledge was important when it came to the craft of sewing, passing the skill from one woman to another. The practical knowledge of women was crucial to the experience of embroidery, as can also be seen by the surviving examples of samplers, such as those at the V&A in London. Samplers are small cuts of fabric that were made by women, usually young girls, to be able to learn and practice the techniques of needlework. A sampler includes rows of practiced stitches and repeated designs and demonstrates the importance of practicing the skill of needlework. When seeing samplers from the 16th century in real life and up close, it is incredible to witness their detail and neatness.

A vital stage when sewing patterns and designs in Renaissance Italy was the process of pricking and pouncing printed paper designs for transfer to fabric. Like Giovanni Ostaus’s The True Perfection of Design, there are some surviving pattern books from the 16th century that were made for women to use to embroider designs from. There are few surviving examples of these designs because of the destructive nature of using them: tearing out a page from the book, pricking the design with a needle, and then using charcoal to shade over the paper that would then reveal the pattern onto the fabric placed underneath. A print from a 16th century textile pattern book by Alessandro Paganino shows women at work together transferring the printing patterns for needlework. The patterns that do survive from this time period perhaps hint at a fascinating history of women sharing designs with one another, passing on their patterns, and each personalizing and changing them to make them their own. However, this skill was really reserved for the most confident of needleworkers at the time. [9]

I went to the Royal School of Needlework at Hampton Court Palace for a day to experience what it was like to learn from the most confident sewers of our day. I found the skill much easier to pick up through demonstrations than through text or image. In the session, we were given the tools and fabric we needed as our teacher demonstrated how to embroider a flamingo, of all things! She would demonstrate a stitch—chain, split, stem—for us to copy, giving us small tips along the way that I still integrate into my embroidery on a daily basis, such as how to tighten the fabric in the hoop in a certain way so that it is as tight as a drum, how to separate threads from embroidery floss without any knots, or how to let the needle drop when threads become twisted in the middle of an embroidery stitch. These are all things that have become part of the rhythm of sewing to me. This transmission of knowledge from one sewer to another is crucial to the craft.With YouTube and social media, this transmission is easily recreated and thankfully has enabled so many people in isolation and lockdown to create using the advice of those via a screen. And yet, there is something about the physicality of a tutor coming up to look at your work and feeding back on a particular stitch or the way you hold your needle, and the spontaneous conversations throughout the day with the people around you as you sew that forge a real connection between teacher, student, and final object.

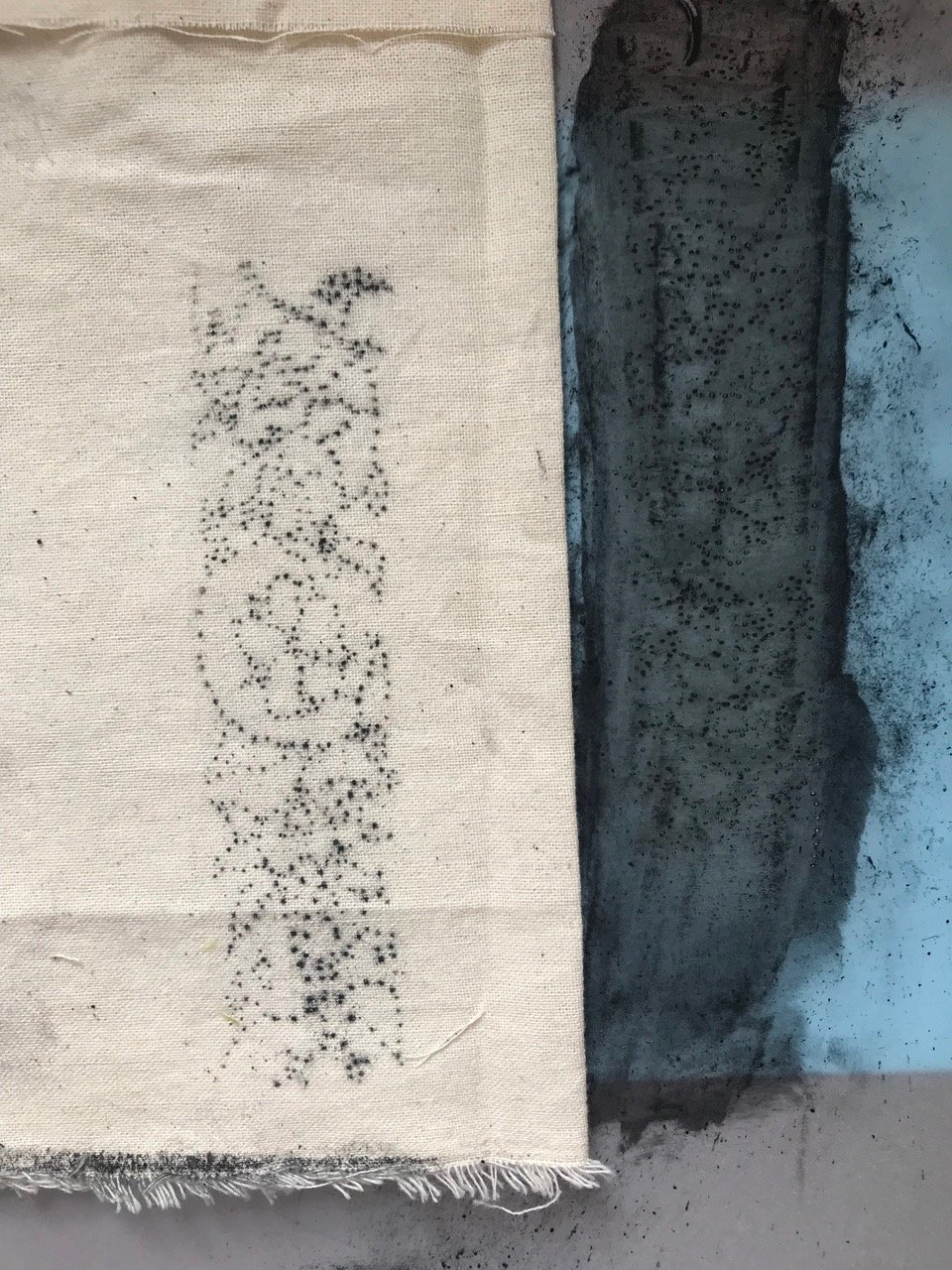

My start to a sampler, replicating some of the stitches found in 16th century samplers. (Image: Louisa Hunt)

Over lunch that day, I sat with a woman 40 years older than me and we exchanged the projects we had been working on: she shared images of her daughter’s wedding dress she had made while I shared photos of my Renaissance-inspired embroidery designs—a fine example of a young embroiderer learning from a much more experienced one. I felt inspired and, despite our different levels of experience, I also felt equal to these women. I had the opportunity to sense what it was like to sew among a female networking group, exchanging conversation as we embroidered, encouraging each other and sharing ideas and designs. I learnt how important it is to sew together: it is such a physical experience and by sewing together as women, I felt empowered and a strong sense of connection to women I had never met before in my life.

In two years of the pandemic, at-home pastimes like sewing and embroidery have risen in perceived value, as they both occupy anxious and idle hands and, through technology, can fight a general sense of disconnect. By sewing it is possible to make something tangible with our own hands, and much like 16th century women would have felt, sewing can give us a strong sense of achievement. I do not take for granted the value of inherited knowledge and skill. Sewing as a social activity is a way to express oneself and creatively share ideas. As threads stitch together to create beautiful clothes and decoration, the act of embroidering together has woven many networking groups over time and I hope that it will continue to do so.

Notes

[1] Femke Speelberg, "Fashion & Virtue: Textile Patterns and the Print Revolution, 1520–1620”, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 73, no. 2 (Fall, 2015), 43.

[2] Carole Collier Frick, Dressing Renaissance Florence: Families, Fortunes, & Fine Clothing (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002), 19.

[3] Janet Arnold, Patterns of Fashion 3: The cut and construction of clothes for men and women, c. 1560 – 1620 (London: Macmillan, 1985), 3.

[3] Femke Speelberg, "Fashion & Virtue: Textile Patterns and the Print Revolution, 1520–1620”, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 73, no. 2 (Fall, 2015),19.

[4] Carole Collier Frick, Dressing Renaissance Florence: Families, Fortunes, & Fine Clothing (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002), 40.

[5] Janet Arnold, Patterns of Fashion 4: The Cut and construction of shirts, smocks, neckwear, headwear and accessories of men and women c. 1540-1660, (London: Macmillan, 2008).

[6] Kathryn Goodwyn, “Flowers of the Needle Volume VII”, 2001, http://flowersoftheneedle.com/FoTN-Vol7.pdf

[7] Carole Collier Frick, Dressing Renaissance Florence: Families, Fortunes, & Fine Clothing (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002), 42.

[8] V&A, “Embroidery Pattern Books 1523 – 1700”, http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/e/embroidery-pattern-books/