Save the Garment Center

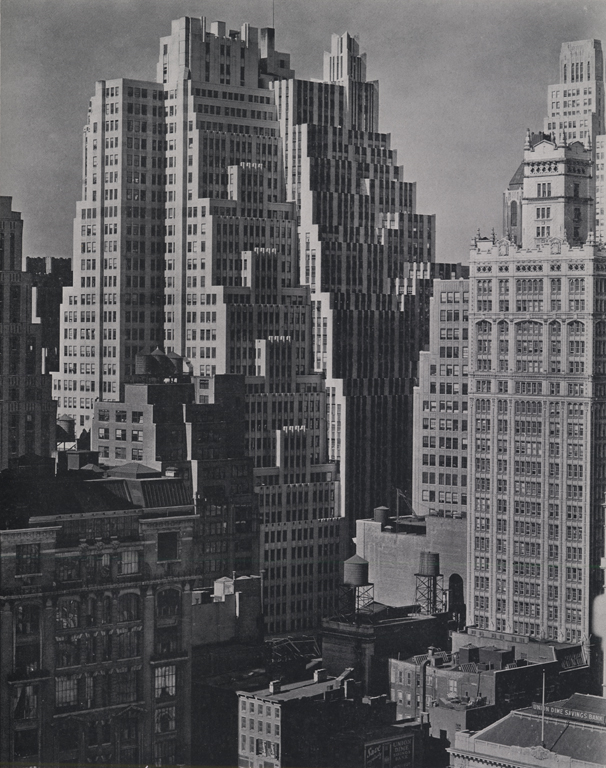

One Monday in May, I found myself at an event titled “How to Keep Manufacturing in NYC: The Garment Center and Beyond” hosted at The High School of Fashion Industries in Manhattan. The exterior of the building is distinctly Deco with towering, streamlined columns rising to a weathered facade spelling out the name of the school in clean, architectural lettering. Above the entrance, four mosaic panels show hands at work. In one panel, a golden measuring tape winds its way through the frame while a hand grips a pair of scissors. In another panel an abstracted dress form sits in the background, while a hand gently holds a sewing needle between thumb and forefinger. When the school opened in 1940, as the Central Needle Trades High School, its mission was to train a fashion workforce in core vocational skills: machine work, garment cutting, draping, tailoring and sewing. [1] Today the school prepares students for college. The curriculum is still focused on fashion, but the coursework guides students toward careers in design, merchandising, and management.

The goal of the event was to discuss the state of fashion manufacturing in New York City, which has shifted dramatically from the New Deal era that fostered institutions like The High School of Fashion Industries. Since its peak in 1950, the garment manufacturing industry in New York City has lost more than 95% of its workforce. [2] In 1987, the city put zoning regulations in place to preserve the remaining apparel manufacturing cluster in midtown Manhattan, known as the Garment Center, but these jobs have continued to disappear. On March 22, 2017, the city’s Economic Development Corporation (EDC) presented a proposal to lift the Garment Center’s zoning protections, which led to the event I attended in May. [3] This is not the first time changes have been proposed, and on each occasion they have been met with a swift and cohesive action from the fashion industry.

As a fashion researcher, I was interested in the relationship between craft, creativity, and policy, but I was also deeply concerned about what these changes would mean for the city and the individuals who labor in this space. What was motivating the city to consider removing these protections now? How would fashion manufacturers cope with this change? Where were garment workers’ voices in this process?

METHODOLOGIES

I felt that these questions necessitated a more intimate form of research than I was familiar with conducting. My academic work has focused on bridging Fashion Studies and Digital Humanities — two disciplines which have allowed me to hide safely within the archive or behind a computer screen. For this inquiry, I wanted to speak with the individuals who would be most directly affected by the proposed changes. I still intended to apply Fashion Studies and Digital Humanities methodologies, but I wanted to layer in qualitative discoveries from in-person interviews and on-site visits.

From the outset, this project was strictly a fact-finding mission. I had already spent countless hours in the Municipal Archives combing through census records and previous studies on the Garment Center — including a fascinating master’s thesis written in 1961 by a candidate in City Planning at Pratt Institute. Clearly, the tension between manufacturing and development in this city was not new. I had also spent many fruitless hours battling with the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Public Data Application Programming Interface (API) trying to extract meaningful population numbers on fashion and fashion-adjacent labor. Dealing with imperfect data is part of the Digital Humanities process, but the most vexing gap in this research was the missing human element.

After discussion with colleagues in different disciplines and friends outside academia, I settled on a hybrid strategy for approaching this project. My plan was part amateur photojournalism, part oral history. I wanted my research to be a conduit for sharing narratives, visual and spoken, about the current realities of apparel manufacturing in New York City. I prepared guiding questions, downloaded photo release forms from LegalZoom, cleared vacation photos off my DSLR, and dusted off an archaic digital voice recorder that had been sitting in a desk drawer for years.

As I prepared my new kit of research tools, I mulled over the challenge of approaching subjects to interview. Despite the timely nature of this inquiry, I was also cognizant of how overburdened and pressed for time these individuals would be. Would they even want to talk to me? I was acutely aware of my own shortcomings as a qualitative researcher. What if I asked the wrong questions? What if I offended someone? What if I caused unintentional harm? These questions had never troubled me with prior research, but suddenly I felt paralyzed.

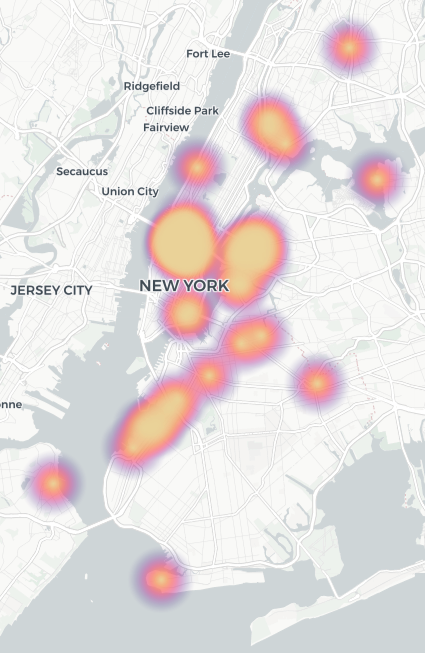

To combat this paralysis, I decided to be forthright about my concerns with the garment manufacturers, who luckily turned out to be very understanding and, if initially confused by my project, ultimately supportive. My sample subjects were pulled from the CFDA’s Production Directory, which at the time of writing listed 141 facilities specializing in sewn goods services (including sample making, pattern making, sourcing, cutting, dyeing, trimming and embellishment). [4] This number represents a subset of the roughly 1,500 garment manufacturing firms that the EDC counts citywide — a number which was roundly criticized at The High School of Fashion Industries event for being too low and not accounting for the breadth and variety of small-scale producers. [5] By working with this small sample set, all located within the Garment Center, I was able to approach my research from a new angle, anchored around the individual rather than the aggregate. My goal was for these two methodologies — the close reading and the distant reading — to work in tandem to inform my project. My hope was that by inviting subjects to speak candidly on their personal experiences laboring in this space, I would be able to gain some insight into the complex ecosystem that makes up the Garment Center.

CHALLENGES & READJUSTMENTS

One of my greatest concerns in approaching this project was that my intended subjects would have no interest in being interviewed. As it turned out, the garment manufacturers were very generous with their time, but also very concerned with their privacy, which I had not fully anticipated. I had predicted some resistance to photography and audio recording, since most people experience a level of discomfort when a camera or a microphone is pointed at them. Indeed, from the first site visit onward the photo release forms were repurposed as notepaper. Although a handful of people were willing to be photographed, it was under the condition that I check with them before sharing the images in any kind of public way. Perhaps I was too aware of my own presence in the room, but even a notebook felt too formal and officious. I opted instead to focus on key phrases and quotes rather than full interview transcriptions. Audio recording proved impossible because even when subjects were willing to be recorded the sounds of the workshop drowned out the conversation.

I had also assumed that manufacturers would be disinclined to share clients’ names (and I had no intention of asking), which did turn out to be true. However, they were willing to share the end destination of their creations and high-end department stores came up across several conversations. In fact, I found the manufacturers to be eager to prove the quality of their production — something that I had never doubted in the first place. I was reminded of the early struggles of Eleanor Lambert in establishing what would eventually become New York Fashion Week, fighting an uphill battle to prove that fashion can happen here, that fashion is already happening here. The manufacturers shared a pugnacious outlook that seemed to be informed by the precarious nature of their situation in the Garment Center. Any initial hostility I encountered melted away when I was able to demonstrate my earnest appreciation and respect for their work.

The biggest communication hurdle, however, was not with the garment manufacturers, but the garment workers. I was wholly unprepared to interview them and felt foolish and intrusive in ways that I had not anticipated. The first barrier was language. In any given shop, there might be five or six different languages spoken, and I had fluency in none of them. This did not appear to hamper production — I observed the workshops humming along seamlessly with gestures and shared words — but my prepared questions were too convoluted or misguided to deliver in this manner. I had woefully underestimated the loaded nature of my physicality in their space as a white woman, largely unexplained, asking questions in English. The workers initially reacted to my unfamiliar presence in their workspace with suspicion and clear misgivings, and I had to fight against my nature to push through their discomfort and my own awkwardness.

Despite the language barrier, once I could get one person to engage with me, others would open up as well. I abandoned my DSLR early on and switched to a wide format Instax camera. The point-and-shoot setup was more forgiving in the workshop light and foolproof despite my nervous hands. More importantly, the instant photos provided an immediate bridge between me and my subjects — no words required. I also liked the connection between physical film and the manufacturing process. In a digital world where we see facsimiles of garments on a runway and in a fast fashion shop, where we collect and manipulate digital representations, there was something very fitting about a tangible form of media to capture the embodied experience of garment construction.

Thoughts & NEXT STEPS

I am deeply grateful to the business owners and workers who shared their time with me and gave me a better understanding of the work that they do. I left each site visit with a deepened appreciation for fashion production and a renewed belief in the importance of preserving the Garment Center and providing for a future of fashion manufacturing in New York, and the United States more broadly.

These businesses are mostly family owned, with knowledge passed through generations. The handworkers are often family members or have been with the workshop for decades, bringing their own unique skills to the studio. There are few young people in fashion manufacturing, so these workers are increasingly hard to replace once they are gone. Design has received all the glory in recent years, but the quiet magnificence of a master pleater or leatherworker should not be overlooked. The flurry of activity around each of these businesses shows that the fashion industry relies heavily on these hubs of skill and expertise.

It is my hope that this micro-project develops into a larger study to properly and thoroughly examine the current status of the Garment Center, before any drastic changes are made. There are several proposals looming and it is crucial that policymakers take the time to listen to these populations before forging ahead with imposed-from-above directives and initiatives. The knowledge and expertise that resides in the Garment Center is essential to New York’s position as a global fashion capital. While these manufacturers serve high-end and established brands, they also cater to independent designers and students. Taking away this channel for newness and innovation would be tremendously destructive for the creative fashion work that takes place in this city.

Notes

[1] “School History,” accessed February 1, 2018, The High School of Fashion Industries, http://fashionhighschool.net/apps/pages/index.jsp?uREC_ID=128884&type=d&pREC_ID=255227.

[2] Amy Dufault, “Save the Garment Center Wins Leadership & Community Building Award,” Brooklyn Fashion + Design Accelerator, accessed February 1, 2018, https://bkaccelerator.com/positive-impact-awards-save-the-garment-center-wins-leadership-community-building-collaboration-award.

[3] Scott Stiffler, “Critics Rip Garment District Alteration Plan,” Chelsea Now, accessed February 1, 2018, http://chelseanow.com/2017/03/critics-rip-garment-district-alteration-plan.

[4] “Resources | CFDA,” Council of Fashion Designers of America, accessed February 1, 2018, https://cfda.com/resources.

[5] “NYCEDC Announces $51M Support Package for NYC Garment Manufacturing Industry,” New York City Economic Development Corporation, accessed February 1, 2018, https://www.nycedc.com/press-release/nycedc-announces-51m-support-package-nyc-garment-manufacturing-industry-collaboration.