Reflections and Observations on the QUARANTINE S/S20 Archive

The 2020 Covid-19 pandemic rendered tens, if not hundreds of millions of people homebound. The ‘home office’ and ‘work from home’ was at least temporarily normalized for many, while others were furloughed or let go from their places of employment altogether. We — Doris Domoszlai-Lantner and Anna Zsófia Kormos — were no different. Both in the fashion industry, we also watched the gravity of the situation unfold from our homes in New York and Budapest, respectively. As a fashion historian and archivist (Doris), and designer and researcher (Anna Zsófia), we paid special attention to the pandemic's effects on the fashion industry, discussing not only the latest news in mass media fashion outlets, but also sharing our thoughts and anecdotes about what we ourselves were witnessing and experiencing.

One of the topics that inevitably surfaced in our conversations was that of at-home, or "work from home," attire and how it compared to that of the workplace. In just a few weeks time, both of us had already experienced major changes in our usual dress practices while we were quarantined. The majority of the time, we wore sweatpants and sweatshirts, and comfortable clothing that we otherwise wouldn't have worn to work, and found that our boredom with these outfits propelled us to dress up like we normally would every once in a while. We were curious to see if others had experienced the same effects, or if they were trying to keep their dress practices, and if that would change as time passed. In light of these questions, we decided to create a project that aimed to find out how others were experiencing the same major event in other parts of the world. We created QUARANTINE S/S20, a digital Instagram-based archive of sartorial stories from the Covid19 pandemic.

In an open call for contributions, we asked participants to submit a photograph of an outfit they wore during the time they were quarantined, as well as a short explanation of why they were wearing those specific garments and accessories. In an effort to get the project started, we posted our own quarantine outfits first, and sent the call for submissions to our friends. We saved every submission that we received in multiple formats and file folders. Photographs were renamed photographs according to a naming convention we devised, and saved together; accompanying text was named for easy cross-referencing, and saved in an ongoing document. Upon inputting the submissions on the design layout we created, each one was saved in another folder. This process ensured that each participant’s original submission was kept in addition to the fully formatted entry that was posted to the public archive on Instagram.

During this roughly 6-month open submission period, the project received 153 submissions from 26 countries around the world. Because we are based in New York and Budapest, it was not surprising to see that the majority of the submissions we received were from those two countries. Two key participant groups that we observed were what we have named Fashion-Based Contributors, and Non-Fashion-Based Contributors. The Fashion-Based Contributors group is made up of 69 individuals from various professions within the industry, including clothes and accessories designers, set and costume designers, stylists, make-up artists, fashion historians and archivists, and vintage collectors. The Non-Fashion-Based Contributors group consists of 84 individuals from varying professions, including a financial advisor, visual and performing artists, professors and lecturers, an esthetician, marketing professionals, and more. As such, Fashion-Based Contributors accounted for 45% of the total participants, while Non-Fashion-Based Contributors accounted for 55%.

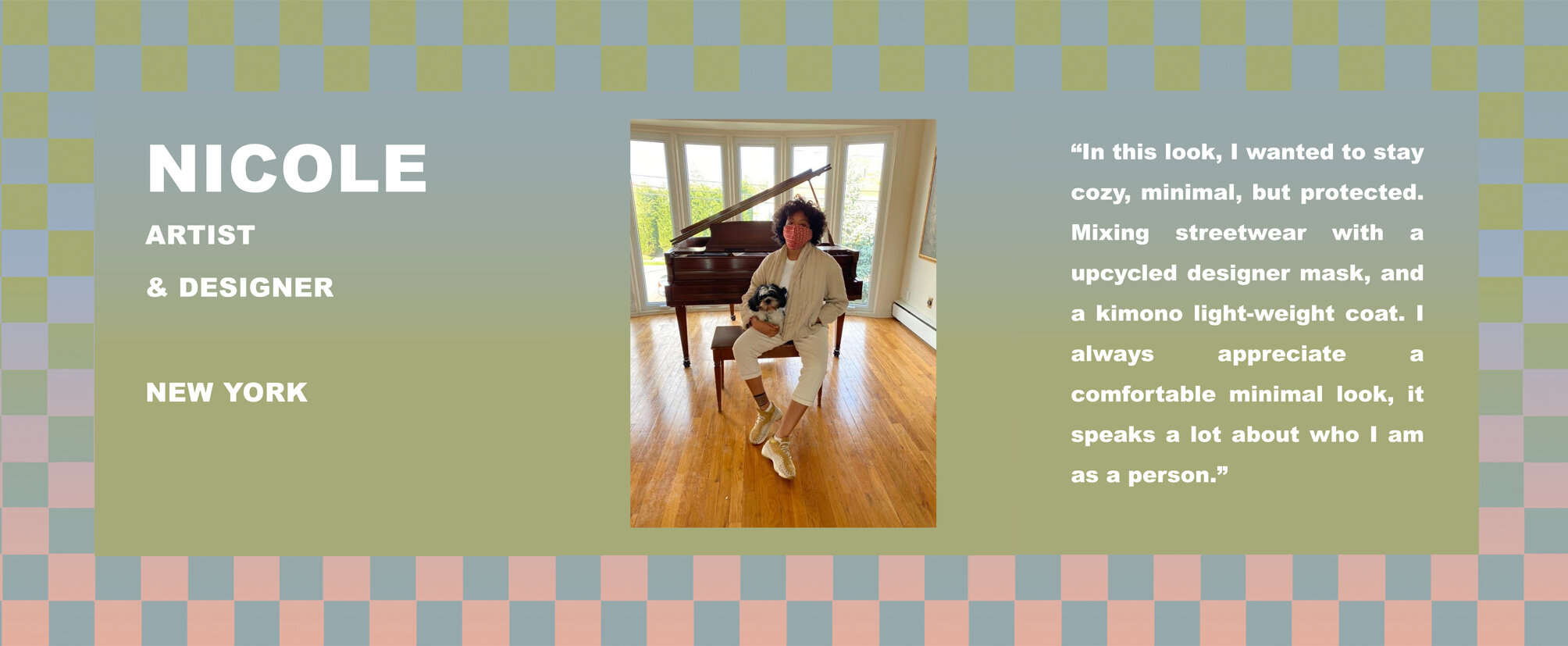

One major pattern that we observed was that of comfortable clothing. Many participants sent in submissions in which they were wearing flowy, open garments such as kimonos and caftans, or athleisure and loungewear such as sweatpants, hoodies, and leggings. For example, Dina, a video editor from Budapest, stated “my motto was: You can’t go wrong with a comfy pair of sweatpants, an airy kimono, a little bit of lipstick and of course a soda to chill the whole day through.” During this turbulent period of time, Nicole, an artist and designer from New York, sought the feeling of protection; she stated that “in this look, I wanted to stay cozy, minimal, but protected. Mixing streetwear with a designer mask, and a kimono light-weight coat.” For some, including Elodie, a lecturer in beauty politics in New York, nostalgia—brought on by wearing vintage garments—provided protection. In her submission Elodie stated that “I am wearing a vintage dress that is a copy of what I wore when I was a child in the 1970s. That makes me feel protected in my castle.”

This year, the search for protection highlighted a small, specialty accessory: masks. Although masks were a relatively common addition to peoples’ outfits in East Asian countries before the Covid19 pandemic, they were adopted by others and even mandated by governments worldwide. Twenty five submissions to the archive illustrate the various types of masks, and the broader category of facial coverings, that have become staple pieces in our wardrobes during this time. These submissions include medical-grade, textile, and designer masks, scarves and bandanas, and plastic face shields. Some submissions showcased homemade solutions, such as Caroline, a costume and dance historian from Boston, whose friend made her a mask “from a fabric that reminded her of her mother’s English garden.” Monica, an artist and illustrator from Austin, Texas, joked around with the masks that she made, calling them ‘snoot boots.’ Posing with two masks cupped around her breasts, she wrote that “this was a total throw together comfort outfit where I was digging through my fabric and sewing masks…. Seeing the shape of the last two snoot boots I made I couldn’t help trying them on as a bikini though!” Others took a more serious approach. Jaimie, a casting director and podcast host from Los Angeles, noted that her masks have allowed herself to express herself better. Jaimie wrote that “someone [she] used to know told [her] I should always pretend to be happy… and I tried, but who wants to live in a fake reality portraying false emotions? Wearing a mask makes me feel free to express anything I want underneath.”

The timely creation of the archive allowed us to document peoples’ dress choices and the reasoning behind them in real time during this historic period, and in a publicly accessible format. As such, the QUARANTINE S/S20 archive may prove to be a useful tool for researchers who are interested in sartorial practices and how they are affected by external events. We will continue to maintain and expand upon the project— gathering observations and data from the contributions we’ve received — in order for it to serve as a community page and resource for participants and researchers alike. Please visit us on Instagram at @quarantine_ss20 to view more submissions from the archive and contribute your own sartorial reflections from the Covid19 pandemic.