Peep This Insta: @fools.and.mortals

Alexis Walker is the assistant curator of Costume and Textiles at the McCord Museum in Montreal by day, and the self-taught embroidery artist behind the Instagram account @fools.and.mortals by night. Both of these sides to her practice have roots in her training in the MA Fashion and Textile Studies program at FIT and her years spent as a fashion professional. On the one hand she researches, aides in managing a collection, and assists in curating exhibitions on an award-winning team (including a 2018 Richard Martin Exhibition Award for their show ‘Fashioning Expo’!); on the other, she connects to the age-old creative tradition of woman embellishing textiles by hand.

She is also my friend and playdate buddy alongside our 4 year old boys, two corny guys who go crazy for candy and superheroes. She’s such an impressive juggler of all these things and her approach is so thoughtful that I wanted to know more about what drives and inspires her creative side hustle. I went in knowing something of her aesthetic (mystical symbolism with a spooky edge) but was surprised that our conversation looped around to meditation and solitude, women’s work and activism, and the figure who brings all this together for her: a patriarchy-smashing art-magic witch who lives vividly in her imagination.

Alexis taught herself to embroider as a hobby during her years as a grad student. She says it grew naturally from the daytime handling of beautiful handmade historical and ethnic textiles that was part of the research she conducted at the Textile Center at the Museum at FIT. As she says, “Studying fashion, you just look at clothes from all over the world, and it’s so inspiring when you see and touch it in person.” The stitching and beadwork in First Nations and Native American clothing were particularly resonant for her. She was living apart from her partner during those years and found herself with many quiet evenings to spend tooling around with needle and thread, attempting recreations of the handwork she saw during the day. She would use found materials like bits of old flags and lace, and began with stitching song lyrics that felt poignant to her. She mentions how grateful she was for the access she had as a student to not only the materials themselves but to written sources where she could look up the names and histories of particular stitching techniques.

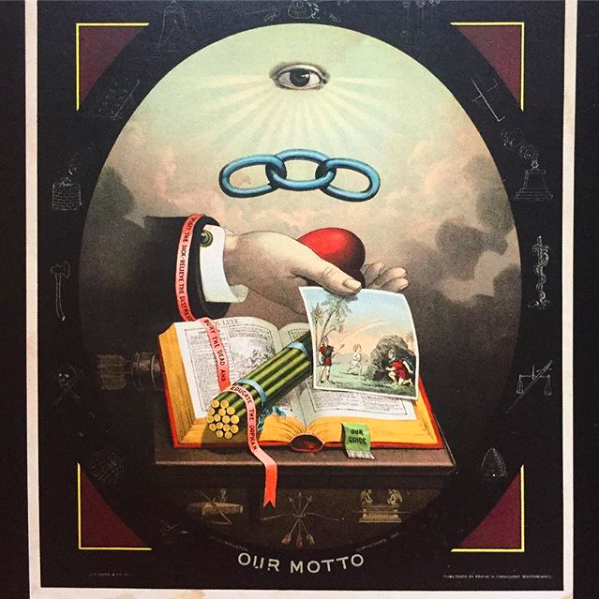

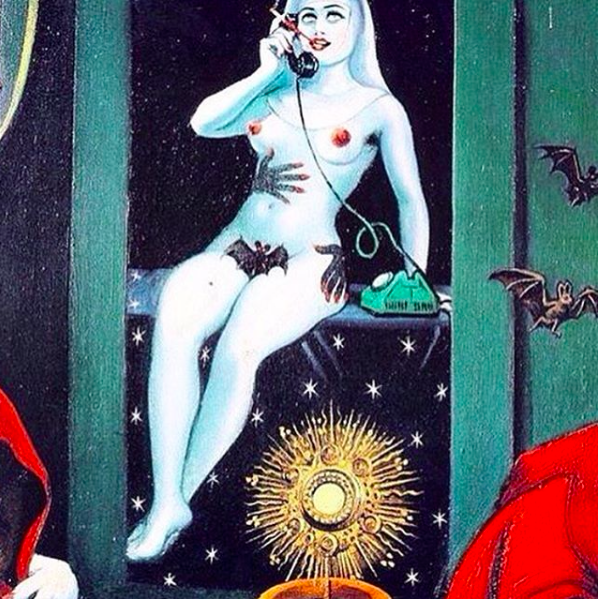

These days she shares images that inspire her on Instagram among the pictures of her own work. Recent examples have included an appliqued skull from a 17th century Spanish funerary robe, an 1830s mourning pendant, and a Hermann Hugo engraving of a skeleton. If these sound a little morbid, that’s…fair. She works a lot with the imagery of death, like the Victorians and the punks before her, though these may seem like unconventional themes for the highly feminized realm of needlework. She traces this attraction back to Catholic school, where church imagery tickled some part of her brain that both fascinated and freaked her out. This came to feel of a piece with other visual interests like Egyptian hieroglyphs, Mexican Catholic and Masonic imagery, alchemical manuscripts, and the visuals of witchcraft and the occult.

The @fools.and.mortals feed is mostly her handmade embroidered patches, which feature talismanic imagery like god’s eyes, flaming hearts, and snakes on felt grounds. They range in size and complexity of design, but most feel destined for the backs of jean jackets, which was in fact the original concept that got her into the patch game. Looking back through the feed, I see that the patches evolved from some less obviously functional wall hangings and charms that shared a very similar look – she says this was the result of a custom jean jacket request and that the move toward patches felt like hitting the nail on the head and finally getting what this practice was supposed to be about, how these skills she’d developed were meant to be applied. She figures that there’s a certain unity to this format and the type of imagery she’s most drawn to. “People have been using these symbols protectively forever.” Indeed, I think the appeal of putting an extra eye on your back once in a while is pretty obvious!

Perhaps unfortunately, someone in the product development department at Anthropologie agreed about the appeal of her patches, and slid into her DMs about a “collaboration” with the chain. Knowing this implied unfair terms at best and outright theft at worst, she refused and posted about the exchange. “It actually reminded me of two pieces of advice I have been given with respect to making art – first, “Say yes to saying no,” and “You’ll know you’ve made it when someone else starts making money off of your work.” […] I’m going back to my needlework and good vibe bubble.” Resigned to having her worst judgments about the fashion industry confirmed, she moved on to a more meaningful collaboration with fellow instagram creator and enamel pin maker KWT Designs (@kwtallantdesigns). Two original pin designs recently went on sale in both of their Etsy shops.

The “good vibe bubble” she writes about is an important part of what keeps this hobby attractive to her. As much as she likes the aesthetics of hand sewing for its imperfection and resilience, she stresses that the “meditative and record-keeping aspects” are equally important to her practice. “I find the repetitive, sometimes tedious aspect of hand sewing very therapeutic – it’s a solo, reflective, and relaxing activity for me.” The passage from graduate student to working mother has seen a number of difficult years, and she says that the simple act of focusing on process, of going stitch by stitch in the creation of something, has become a necessary refuge inside her daily life. Mothers hear so much about taking time for self care, which can often sound indulgent and contradict the rest of the messages we receive about selflessness and virtue; within this climate, I’m especially impressed that she has carved out this niche for herself in which she is quiet and contemplative, but also creative. Not to mention bringing in some cash on the side, getting to make custom things for her friends, and indulging her dark and spooky side to a productive end.

““I find the repetitive, sometimes tedious aspect of hand sewing very therapeutic – it’s a solo, reflective, and relaxing activity for me.””

Alexis has gotten lucky (is there really such thing in design? That’s a question for another day) that the look and function of her patches has caught on with other people and made her side hustle something she can successfully sell and promote on social media. But the idea of churning out a product is antithetical to her quiet, reflective adoption of this old-fashioned practice. She has a history of hustling, selling things she’s made, but this time around she’s grateful that the economic pressure is off; her job at the museum frees her to pick and choose which embroidery commissions she takes on. If someone gets in touch with an idea for a custom piece, she’ll consider whether it fits into her own aesthetic before agreeing to do the work. “As soon as it becomes demanding I’ll just say I’m not interested.”

One commission that she accepted immediately came from her best friend, the musician, artist, and Indigenous rights activist Tanya Tagaq. “I’d make her whatever she wanted, but this piece was shit disturbing par excellence, which I love, so of course I did it,” she says. Tagaq was set to be appointed to the Order of Canada, among the highest honors in the country, at a ceremony presided over by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, and she wanted to wear a jean jacket with a patch made by Alexis featuring the acronym UNDRIP (for the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, the adoption of which in Canada has been slow-going, contested, and incomplete), decorated with flowers and three teardrops in red, black, and blue, representing blood, oil, and water. The visual impact of this patch in that formal, ceremonial setting would have been radical and powerful; alas, the dress code ended up forbidding it. “She’ll still wear it elsewhere,” says Alexis. And plans are the in the works for the creation of smaller versions or pins with Alexis’s design to be sold at merch tables on Tagaq’s tours.

As we spoke, a number of themes began to coalesce: of women’s handwork as an almost spiritual practice, of clothing as a tool for activism and change, and of the imagery of death and mysticism. Together they arranged into a very witchy picture, which is no surprise, as the witch is a figure with whom Alexis identifies intimately and takes as perpetual artistic inspiration. “To me,” she says, “the witch is a powerful woman who has chosen to live an independent life outside of the status quo, and presents a direct challenge to patriarchal structures.” She sees the act of making art itself as magical and ritualistic, conjuring beauty from, in her case, felt and thread, the needle as tiny magic wand. “On the eve of my 40th birthday,” she wrote me after our conversation, “I can’t help but think a lot about witches, and in particular the archetype of the crone. Through a misogynistic filter, the crone is the barren, lonely old woman who has failed her social and biological role of mother and wife. To me she has become an inspiration – I see her as the old woman who through her own self-awareness, lack of ego, strength, creativity, and magic has reached a point where she needs nothing she doesn’t already have within. She can make things happen by the strength of her will. She reaches a level of empowerment and enlightenment that is unattainable to men. I have made a promise to myself that by the time I reach 60, I want to be a full-blown witch: an artistic magician, not distracted by what society says I should do or be, not reliant on anyone for superficial fulfillment, living a simple life that is very, very free.”

I can’t recommend highly enough that you follow along on this witchy journey on Instagram @fools.and.mortals

Product and inspiration images courtesy of @fools.and.mortals

Do you know a fashion-related social media account you'd like to profile for our Weeklies? Tell us about it at info@fashionstudiesjournal.org