The Profit Value of Dress to Protest

At the recent March4Women rally in London there was plenty of evidence that we are all paying attention to how we display our political values. Marchers appropriated various historical styles of protest dressing; classic Suffragist costumes in white, violet, and green, “hippie” counter-culture style from the 1960s, as well as contemporary slogan t-shirts galore, both homemade and store bought. It seems there is nothing new in the way we wear our principles. This got me thinking about the cyclical nature of borrowing from street-style; a style that both signifies publicly what we believe in, and makes complex political messages more approachable. As a researcher, I often find that my best ideas for studies start like this, a glimmer of an idea sparked by a chance meeting; politics and revolution began to stitch together in my thoughts.

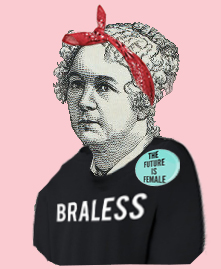

Political dressing is certainly having a moment. References to resistance and protest were prevalent at recent fashion weeks with labels proclaiming their values in allegiance with the liberal left. Missoni pussy-hats, feminist statement t-shirts at Prabal Gurung, "Fuck Your Wall" knickers by Raul Solis, and “we are all human beings” shirts at Creatures of Comfort, to name a few. Fashion designers and brands have often used the catwalk to articulate a political position or signify a collective crusade. The commercialisation of heart-felt values, turning social ills into trends, has an established history, profiting designers through both sales and the publicity from the inevitable controversy. Vivienne Westwood, Alexander McQueen, and Katherine Hamnett have used fashion to focus on subjects that have a bearing on current affairs; each freely expressing their views in the garments they present, just as we are free to wear our heart on our sleeves.

But how does purchasing a political identity fit with an authentic desire to make a difference? I am concerned by the price that is attached to these labelled versions and whether the values they profess to adhere to are reflected in how they are actually produced. Research shows these are not new questions.

Liberty of London could be said to have created a brand by appropriating the political ideas of the Rational Dress Society and suffragette jewellery was created by innovative jewellers to encourage women to send a message of support by purchasing expensive gems. The subversive style of the Zazous during World War II was a way to wear resistance, and make it cool, as were the Zoot Suits worn by young Mexican Americans in the 1940s. As Eleanor Roosevelt wrote, "The question goes deeper than just suits. It is a racial protest.”[1] It’s no surprise that the Zoot suit became a way to signify rebellion when it appeared so easy to read, however it wasn’t easily copied due to flamboyant fabrics and extensive yardage being hard to come by during rationing. Perhaps contemporary designers could take note: If they don’t want their catwalk protest looks to trickle down to the streets, make them less easy to copy. Design something truly radical – something beyond slogan-shouting – that says more about the depth of how revolutionary ideas can be embodied rather than surface motifs.

“But how does purchasing a political identity fit with an authentic desire to make a difference?”

In his pivotal book on subculture, Dick Hebdidge points out that youths embraced denim in the 1950s to rebel but the style was soon absorbed into a conventional mode of dressing. Likewise, as John Fiske suggests in Jeaning of America, the Punk aesthetic of holes, pins, and chains – intended to challenge a Thatcherite uniform of ties and shirts – was quickly watered down by both high-end fashion (the famous Versace pin dress) and the high street with ripped slogan t-shirts aimed at twelve-year-olds. I fear we may see pink pussy-hats being sold in Primark, having been manufactured by sweatshop labour and worn with no awareness to the original intention.

I was interested to find out if others at London’s March4Women harboured similar concerns and after speaking with 20 or so demonstrators, I was surprised that the consensus was in favor of fashion adopting current styles of political dress. Most expressed positive feelings that there was an option to buy, rather than make, statement pieces. As one woman explained “Since Trump has come to power I feel it is imperative to wear and express my values at all times, all day every day, I can only do that if fashion provides me with the clothes to do so.” She had waited four weeks for her ‘the future is female’ t-shirt to arrive from Otherwild in Los Angeles and had been tempted to make her own copy but didn’t have the skills, “I wanted it to look good, not homemade.” She said she was happy that labels were responding to the political climate by offering mainstream options as “it normalises the issue and [provides] more options of how to wear what we believe in.”

Even those who were clearly wearing handmade declarations of feminist-fashion at the March4Women felt that not everyone was comfortable being creative and it didn’t matter how the message was worn as long as it was part of an inclusive, important conversation. A group of young women who were declaring “free the nipple” said they were happy to see feminist message t-shirts in H&M as it meant that even “conventional girls were saying something” and it didn’t matter if you weren’t arty.” I was also able to ask a group of London “anti-fashion” designers, who have been producing small run or one-off garments that reflect many of the ideas behind protest-dress, how they felt about the manufactured slogan-wear on the catwalk. This group was adamant that “as usual, fashion wants to make money from copying the energy of the streets.” But isn’t that what fashion does so well? It reflects back to us our own vague feelings in such a way that we feel a connection to the garment because it resonates with ideas which we can’t always clearly articulate. What I love about fashion is the trickle-up, trickle-down, aren’t-we all-in-this-together vision; the patchwork of ideas mirroring who we are and who we don’t know we are yet, allowing us to play with our identities.

At the March4Women I chose to wear a handmade copy of a slogan sweatshirt I had seen at NYFW, stencilling “We Are All Human” on an old pale blue sweatshirt to emulate the Creatures of Comfort sweatshirt designed by Jade Lai as a protest against the prejudiced proclamations of the Trump administration. I loved the idea of appropriating (copying, responding to, stealing) a design that has been pinched from the street, reincorporating it into a march based on principles that are true to my heart; a cycle of virtuous values. I wonder, however, if the label I’m replicating would appreciate my homage to their catwalk look. Is it okay for the catwalk to label values which the anti-fashion brigade feel belong them but not for me to pilfer the design back again?

The V&A Museum’s recent purchase of a pussy-hat for a display unveiled on International Women’s Day exemplifies the important role of dress in these highly-politicized times. And yet, it provokes questions about the connections between protest and profit. As both a researcher and a designer, I am tempted to embark on an interpretive phenomenological analysis on the topic to explore how it feels to wear our values. I think that all my best concepts begin with triggers in real life and research into this topic has left me with several unexplored questions.

Notes

[1] Chiodo, J.J., “The Zoot Suit Riots: Exploring Social Issues in American History,” The Social Studies, 104.1 (2013), 1-14.