Cinderella Syndrome: Curating an Exhibition about High Heels

Returning from a fashionable SoHo party two years ago, wearing the highest pair of stiletto heels I owned, I rushed out, anxious to get home and take those things off. Outside, as I ran to hail a cab, I found myself in the midst of an impressive (and not very graceful) acrobatic flip. I was left kneeling on the sidewalk with a broken Miu Miu heel, a bleeding knee, and countless questions.

That night I hung up my high heels. But I kept wondering about their allure. Would I ever pluck up the courage to strut in heels again? That moment never came; however, a different opportunity to work through my relations with stilettos came from an unexpected source: I was invited by the distinguished Farm Gallery in Israel to curate a design exhibition about them.

When I set off working on the exhibition Cinderella Syndrome: A Journey In The Footsteps of the Stiletto, I wanted to closely examine the love-hate relationship that not only I but countless women and men from all around the world have had with high heels in the last 500 years or so, since they made their first appearance. Previous exhibitions focused on high heels: Shoe Obsession at FIT, Killer Heels at the Brooklyn Museum, and Shoes: Pleasure & Pain at the Victoria and Albert Museum. So why curate another one? First, I knew this was a chance to set up the first exhibition ever to focus on high heels in Israel. Second, my familiarity with Israel's surprisingly-bustling shoe design industry meant I knew I would be able to showcase pioneering, highly creative designs that would display local, independent, and emerging talent. Israel’s design industry is a rather nascent one, just like the country; however, there are over five different and renowned design academies in the country. Bezalel Academy for example was already established in 1906, and the fashion department in Shenkar, for example, the school from which I received my B.A, was recently ranked 10th in the prestigious BoF Global Fashion School Rankings.[1]

The exhibition, which opened in June 2016, featured upwards of 60 works by 45 of the best designers in Israel: emerging talents and veterans of the first rank, as well as outstanding students from the state’s three leading fashion design schools.

Some of the shoes in the exhibition were already-extant; however, to enrich the show and its different themes, I decided to approach various designers and students and ask them to create bespoke shoes, specifically commissioned for it.

We are all used to thinking of shoes, high heels included, as useful, functional items; but most of the shoes in the exhibition were not meant for walking, and for a reason. The freedom to disregard questions of convenience and commercial attributes, I believed, would allow designers to express through the stilettos a story that goes far beyond aesthetics and design. The majority of the shoes in the exhibition were designed and manufactured as one-offs, and sometimes, just like Cinderella's lost shoe, only one shoe was created.

An architectural gem, the Farm Gallery is a 1100-square-foot space that was once a residential house, built in the beginning of the 20th century, divided into four rooms and surrounded by a tree orchard.

Each of the gallery’s spaces was dedicated to a different theme which sought to examine the many contradictory facets of high-heeled shoes: from impossible heights through eroticism and fetishism, fragility, gender and identity, and onto shoes’ transformation from a wearable object into an artistic object in their own right. Thus, for instance, one of the gallery’s spaces was dedicated to fairy tales and the fragility they embody and showcased, among other objects, glass slippers by artist Boris Shpeizman, referencing, of course, Cinderella.

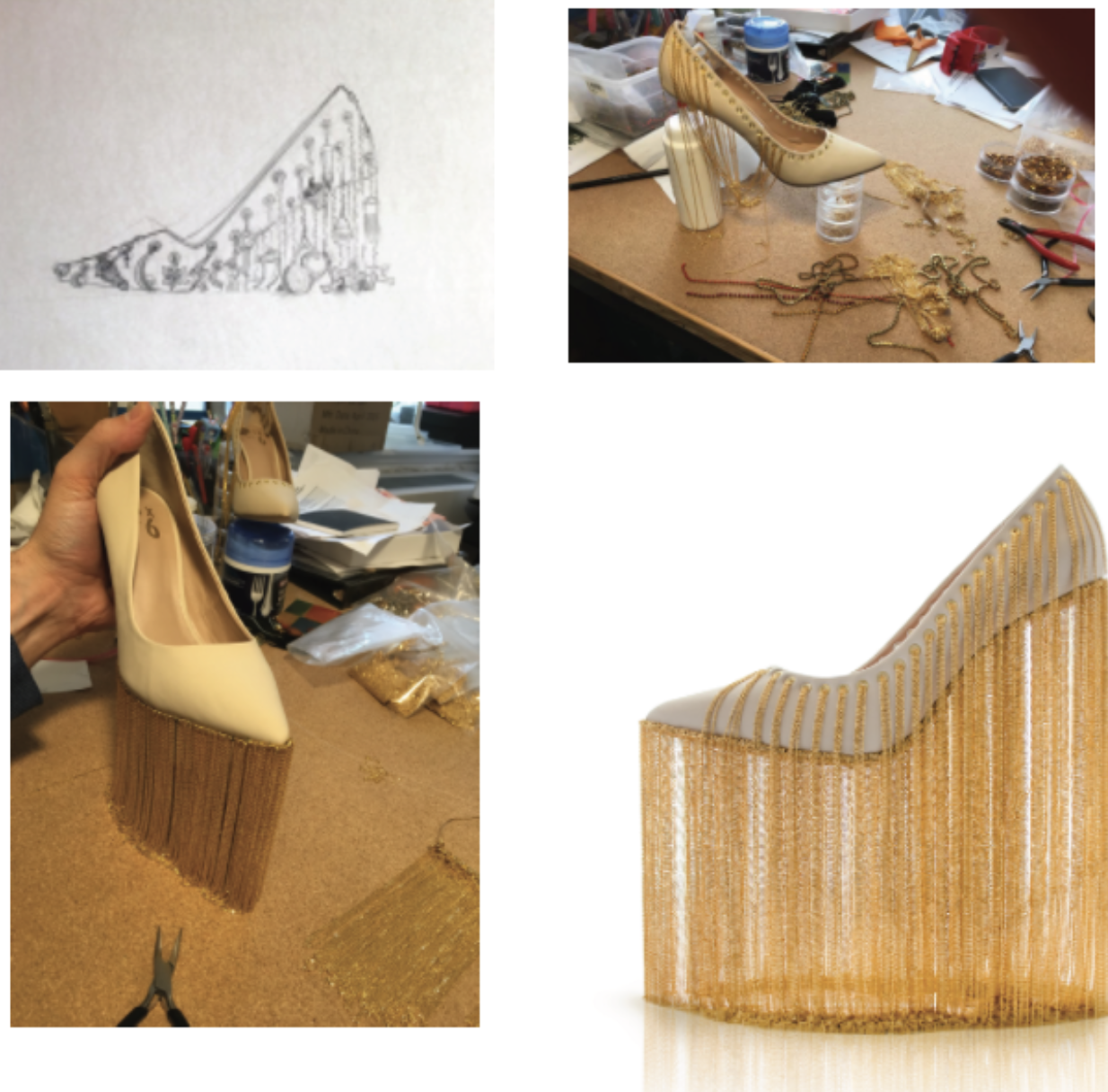

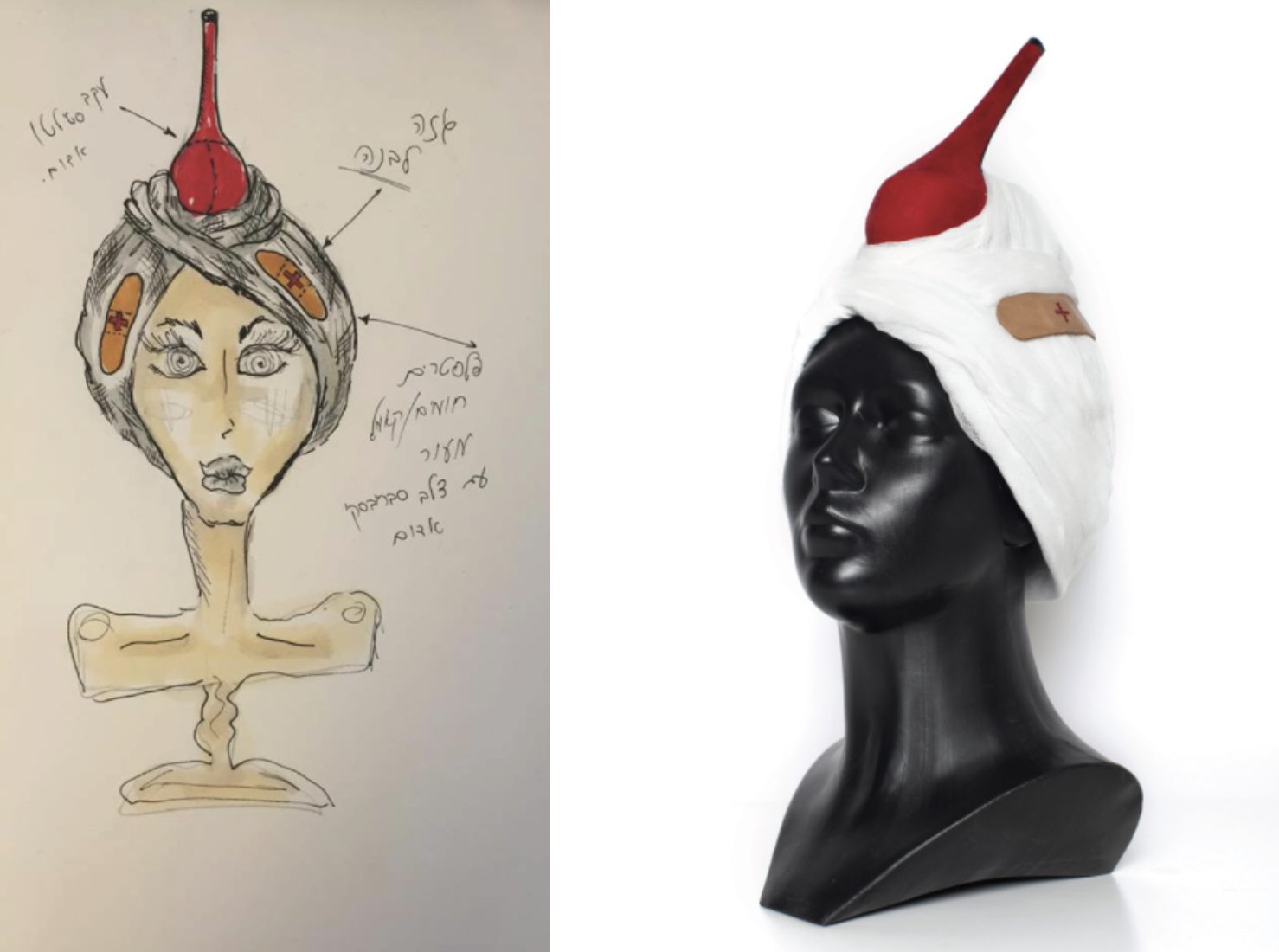

One of the most inspiring aspects of working on the exhibition, for me, was following the artists’ creative processes—conversations, brainstorming, sketches, images arriving from studio desks in the middle of the night—as each shoe was brought to life.

Inspired by the fairy tale of Rapunzel, jewelry designers Nophar Haimovitz and Elad Barouch designed a shoe made out of hundreds of golden chains. Mor Kfir, on the other hand, drew inspiration from the Little Mermaid, creating a delicate, sinister shoe made of fish bones, pearls and freshwater mussels.

Incidentally, when I started working on the exhibition, I learned that The Guild Schoolhad just opened a shoe design course, inspired by the Fairy Tale Fashion exhibition at the Museum at FIT. We teamed up and chose the four leading designs that would later be turned into a pair of shoes.

Another space presented shoes transformed from functional objects into objects of art, featuring wooden, metal, vellum and even cast-iron shoes. Gal Souva’s shoes, for example, were inspired by the game Jenga and crafted from mulberry tree wood, while Lia Mizrav’s were made of olive tree wood, as inspired by Japanese Geta footwear.

A third space was devoted to shoes of impossible heights, such as heels exceeding 30cm (12 inches) in a pair of shoes entitled Acrobat Shoes by Tali Sorit, and shoes fitted with acrobatic wheels made of bicycle wheel spokes by Mark Goldenberg.

The exhibition included several 3D-printed high-heeled shoes by various designers: Danit Peleg’s shoes can be printed in a home 3D printer within 12 hours; the brand Norman and Bella created a shoe the examines the way we walk, and Anuk Yosebashvili designed 'From 0º to 90º’ ballerina shoes.

It seems impossible to discuss the stiletto without examining its fetishistic implications. The exhibition’s “Fetish” space examined the sexual dimensions of high-heeled shoes and included a black headpiece by For Those Who Prey, which was made entirely of stiletto heels and hand-covered with leather, inspired by the Statue of Liberty.

Kay Long, a talented designer, performer and drag queen, created a leather jacket incorporating high-heeled shoes in its shoulders—a symbol of the empowerment she sees in heels, as well as a brilliant homage to 1980s shoulder pads.

Several designers chose to reference pain that high heels can inflict on the wearer. Idit Barak, who always dreamt of wearing heels but has always failed to do so, created crutches fitted with stiletto heels. Orit Freilich subjected a pair of Martin Margiela Replica Collection shoes to an MRI scan.

Tami Bar Lev, who candidly admitted to admiring stilettos but always feared falling in them, created a turban made of embroidered bandages with a red stiletto at its center— an homage to Elsa Schiaparelli’s iconic shoe hat.

The high-heeled shoe made its physical debut in Western culture almost 500 years ago, and from then on the fashion world has had a love-hate relationship with it. Throughout history it symbolized class and power, but as time went by it also became an object representing restriction and oppression, pain and fragility, sexuality and fetishism. It is the only piece of apparel that has simultaneously aroused adulation, revulsion, ridicule and desire—and is one of only a handful of wearable objects that states have gone so far as to legislate against.[2] Last May, Julia Roberts astonished audiences when she scaled the steps of the Cannes Film Festival’s red carpet barefoot, in protest of the demand made of female film stars to arrive at the event in stilettos.[3] Last December, a British office worker was fired after refusing to acquiesce to her company’s demands of donning heels at work.[4] Though some women wish to be liberated of these heels, others find them to be the most comfortable, saying they feel tall and powerful in them. Some women regard them as anti-feminist articles of clothing, slowing down women’s walking gait, endangering and inflicting pain on them; other feminists have adopted them in the belief that women should, in fact, wear whatever they feel like.

Conceptual fashion challenges norms of beauty and conventions of aesthetic and gendered beliefs. Through the exhibition spaces, I aspired to show the multifaceted role of stilettos in fashion. I learned that there’s no clear-cut right or wrong, black or white - the truth is elaborate and intricate, elusive and open for interpretation, and often lies in the eye of the beholder. Cinderella Syndrome thus invited the viewer on a journey: a meandering course between the beauty and the pain, the myth and the reality of one of the most iconic, charged and coveted objects in fashion history.

Notes

[1] “Global Fashion School Rankings 2016”, Business of Fashion. https://www.businessoffashion.com/education/rankings/2016

[2] Valerie Steele and Colleen Hill, Shoe Obsession (Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2013), 23-52.

[3] Cady Lang, “Julia Roberts Went Barefoot on the Cannes Red Carpet”, Time, May 12, 2016, http://time.com/4328745/julia-roberts-barefoot-on-cannes-red-carpet/

[4] “London receptionist 'sent home for not wearing heels’”, BBC, May 11, 2016, http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-london-36264229