The Elusive Art of Selling Smells

By now, you’ve probably seen the ad for Kenzo’s newest fragrance, World, which went viral overnight thanks to its drum-and-bass-fueled soundtrack and off-the-wall choreography, busting the clichés that have made the perfume ad genre so ripe for parody over the years (remember SNL’s take on Brad Pitt’s Chanel No. 5 spot?). The Spike Jonze-directed tour de force starring Margaret Qualley felt like a breath of fresh air to a consumer base tired of the uninspired tropes used to sell scent time and again.

In their defense, however, fragrance ad execs have one of the hardest jobs in the consumer goods industry: they have to sell you something you can't even see. The fragrance market is worth over $30 billion but is that truly the result of artsy black and white montages or photos of celebrities dripping in gold dresses? What is it about this industry that moves product so well, and how does it manage to tap into the emotional and physiological connections we forge through our olfactory senses?

One argument is that the fragrance industry’s tremendous success lies in the basic human instinct of finding a mate. While the existence of human pheromones has yet to be scientifically proven, researchers espouse a connection between certain genes linked to our immune system (Major Histocompatibility Complex, or, MHC), sexual selection and smell preferences. [1] The theory posits that since greater diversity of genes leads to a stronger immune system in offspring, women seek partners whose MHC – identifiable through smell – differs from theirs. A 2012 study published by the International Journal of Cosmetic Science, for example, asked participants to rate various scents commonly found in perfumes, including rose, cedar, cinnamon and moss. Each person's preferences were then cross-referenced with their MHC genes. The findings showed a correlation between which version of a gene someone had and their preferences in smell.

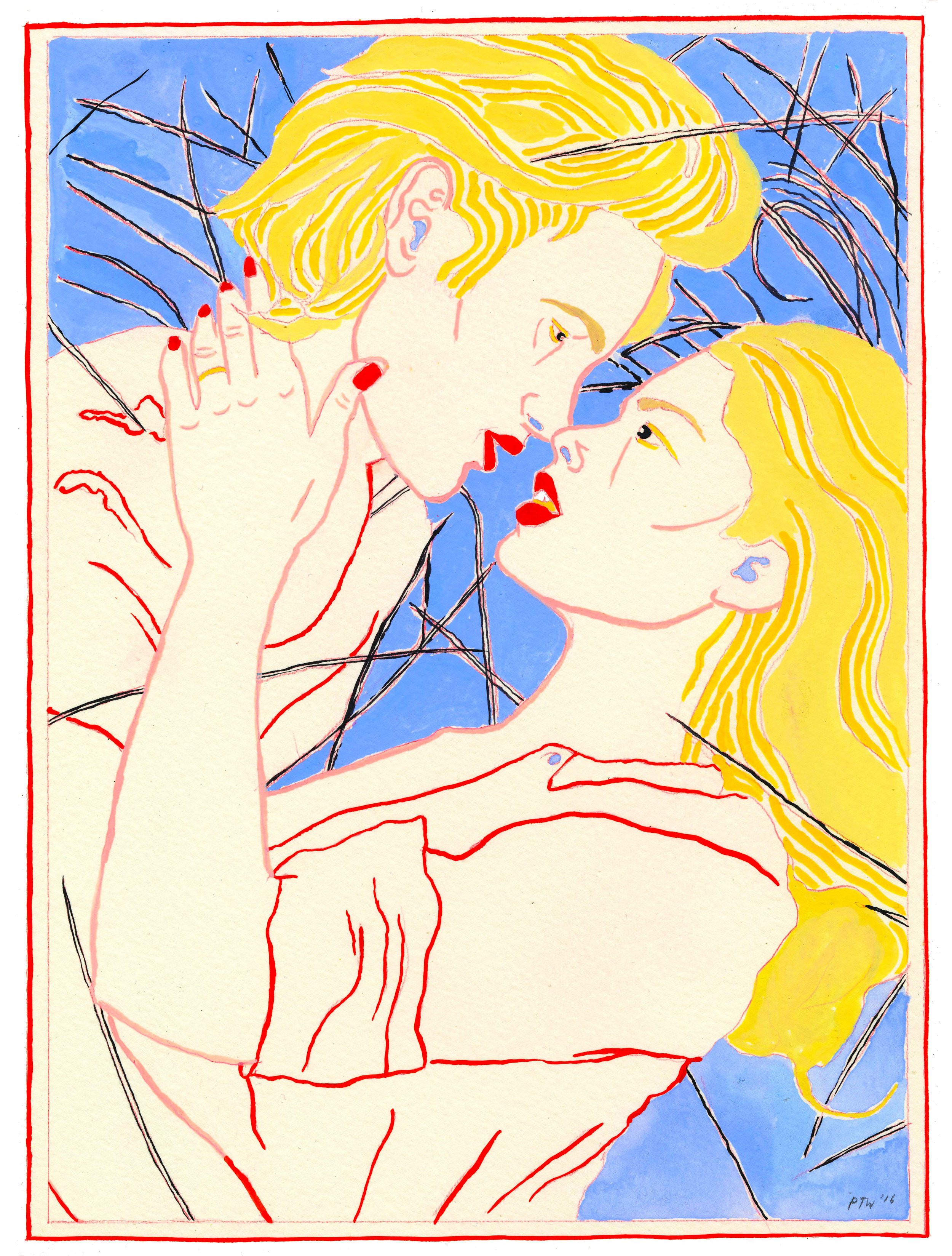

But what does this have to do with advertising? The study also found a significant difference in scent preferences when participants were shown sexually themed imagery alongside the scent, compared to those who were presented with images of just perfume bottles. These findings potentially illuminate the success of using sex to sell perfume, a practice that can be found as far back as 1911 when Woodbury Soap Company turned their struggling sales around by including romantic imagery of couples – or, even more shockingly for the time, nude women – in their advertising. [2] By the time the Swinging Sixties and the accompanying Sexual Revolution arrived, sex was being used in half the perfume ads out there; a 1970 study by marketing analyst Suzanne Grayson found that sex was the central positioning strategy in 49% of the fragrances on the market. [3] As Richard Roth of perfume company Prince Matchabelli said, "Fragrance will always be sold with a desirability motif." [4]

Marketers, then, suggest the power of fragrances through imagery that is as heady and pungent as the product they’re trying to promote. Think literal depictions of objects of desire succumbing to the power of scent – infamous Axe commercials where swathes of beautiful women fall at the feet of an Average Joe come to mind, or more euphemistic interpretations of desire like the heavy eyelid, a sultry whispering voiceover or ascension to some heavenly light. Cue collective yawn.

That’s the amazing thing about perfume: it’s an industry almost entirely bereft of innovation and yet remains one of the most successful sector in the consumer goods market. According to a 2016 report by management consultancy A.T. Kearney, an estimated $800 million is spent on fragrance marketing each year; meanwhile, only six percent of respondents cited advertising as the motivation behind their purchase. [5] What’s the missing piece here?

Once again, science can help to explain these habits. “The areas of the brain that process smell and emotion are as intertwined and codependent as any two regions in the brain could possibly be,” says Rachel Hertz, a neuroscientist and expert in the psychology of smell. In her 2007 book The Scent of Desire, Hertz discusses the role of the amygdala, an area of the brain that affects emotions and memory. The amygdala is connected to the olfactory bulb inside the nose, meaning that incoming smells travel directly from the nose to the part of our brain that fires up memories and feelings. This may explain why certain scents can bring back memories in such vivid detail, and why, marketing clichés or not, fragrances move us – and move us to buy.

Notes

[1] M. Milinski and C. Wedekind, “Evidence for MHC-correlated perfume preferences in humans,” Behavior Ecology 2001, 12, 140-14, accessed October 25, 2016, http://www.labmuffin.com/2013/07/perfume-science-body-chemistry-and-why-you-love-the-smells-i-hate/.

[2] http://www.aef.com/on_campus/classroom/book_excerpts/data/2476

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Kim Bhasin, “Perfume Makers Spend $800 million on Ads That Apparently Stink,” Bloomberg.com, July 20, 2016, accessed October 25, 2016, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-07-20/perfume-makers-spend-800-million-on-ads-that-apparently-stink.