Carlo Casini: We Invented Bell Bottoms

“You know what we did one time? I can’t believe it… we invented bell-bottoms,” the innkeeper admitted, shaking his head and laughing.

It was startling to hear, even from Carlo Casini, a natural raconteur with a long career as a serial entrepreneur in the storied Monte Argentario peninsula of Tuscany. I usually write about society and technology, but I had heard enough stories of my Jewish grandfather’s wholesale garment business in Toronto to be curious about this untold story of Italian fashion innovation. When Signor Casini told me his full bell-bottomed adventure in context, backed up by several original pairs that he retrieved from a warehouse, I was sure this mystery would interest a larger audience of fashion historians and enthusiasts.

My wife and I had spent many summer evenings at his pensione, Verde Luna, in the sleepy lagoon town of Orbetello, listening to episodes from his family’s past and his life’s work. They ranged from cat-and-mouse games of hiding and recapturing property—like a particularly valuable black horse—from occupying Nazi officers, to accounts of the eccentricities and exploits of international executives, movie stars, and aristocrats who docked their yachts and entertained in their villas in the area’s heyday. He witnessed a lot as the owner of a restaurant called “The Pirate,” but he spent most of his time and energy evolving his family’s fourth generation clothing and fabric business. In his telling, his biggest success was conceiving, producing, and promoting bell-bottoms in the early 1960s.

His account was so fortuitous that I was compelled to do some research to see if his claim could possibly be believed. To be clear, Signor Casini was not claiming to know he was the first person in the world, or even Europe, to produce bell-bottoms in the 1960s. What he did describe was his own experience of coming up with the idea, as women’s fashion, from the shape of bell skirts, bringing it into being very early, in 1959 or 1960, and enjoying first-mover advantage and a period of sales without any competition, all within his limited market sector in the regions of Tuscany and Rome. I did not see detailed documentary evidence, such as dated receipts or business correspondence (though I confirmed the existence of the companies involved) but the interviews and images gathered here provide a convincing personal account, and I think it’s worth noting that I did not find any evidence to contradict his memory. Therefore, the purpose of this piece is not to pinpoint the origin of the larger trend of bell bottomed pants, but to share a wonderful little slice of fashion history and show how a craze can sweep through a place, a time, and a life.

The oldest traces I found of the flared trousers were in fashion histories of sailor suits and Chanel’s liberating “beach pajamas” in the 1920s. [1, 2] However, the trail of the latter 20th century craze—which fueled military surplus sales and much trouser alteration by American sailors—leads back to Europe in the early 1960s. [3] The earliest example of the 1960s menswear style I found were pants known as marinettes by a Paris tailor named “Marina.” In 1962, he was said to be “the first to cut” the wide-bottomed men’s trousers, later described as “precursors to bell-bottoms,” which became popular among Parisian minets or “trendies.” [4, 5]

The postwar boom in Italian fashion, which had seen the founding of many major labels, was in full swing as Monte Argentario reached the height of its jet-set popularity in the 1960s, filling every summer with what Casini called, “a nice elite of international society.” In the previous decade the area, undeveloped and half-demolished by American bombing, had transformed itself into one of the “lustre places on the international circuit for lucky house guests.” A La Nazione article from 2013—titled “Argentario, the sweet life on the promontory of the kings”—provides a name-dropping summary of the scene. One of Casini’s clients was the American-born Marchesa Lili Gerini. Her pink villa, Santa Liberata, built in 1948 on a Roman archeological site that once belonged to Nero, was among the top spots. She became an important society figure who brought together VIPs from America and the rest of the world, including famous designers such as Oscar de la Renta. It was against this backdrop that Casini says he created his first colorful velvet “pantoloni a zampa d’elefante,” or “elephant-paw pants” as they were known in Italian.

The area today retains some of the atmosphere of that era, its unique geography creating a world slightly apart from the rest of Tuscany. The promontory is a “tied island,” connected to the mainland by two tomboli with lengthy beaches facing opposite directions. These shelter a lagoon with the town of Orbetello at its center.

I interviewed Casini several times with his two sons in the small reception area of their hotel and in his former workshop next door, where he first produced the pants. He also took me to meet the charming and petite Cosetta (literally “little thing”) Bimbi, the woman whose shape the pants were based on, and the only other remaining participant in their enterprise from almost 60 years ago, who told me stories of meeting Laura Biagiotti and watching Jacqueline Kennedy and Aristotle Onassis docking their yacht and strolling along the corso, evoking the time of her youth when this innovative trouser style epitomized social change and promise for the future.

Interview

The interviews with Casini have been translated, edited, and condensed for clarity.

What were your early experiences with fashion?

My parents had a shop that sold garments and fabric. They were the fourth generation in the business. I learned everything about fabric from them. We had storerooms full of fabric, from before the war, and American surplus after. Since I was a child, I have always been a bit extravagant, imaginative—at seven or eight years old I went in the store and checked out all the fabrics we had and there was a heavy cloth from which I thought of making men’s shirts. I thought, with these beautiful wool fabrics, “How nice they are, what beautiful shirts could come out of these.” I even thought of the design.

What was this area like back then? When the VIPs came, were they already looking for clothing, or did you have to make an effort to attract them and sell to them?

It was still a simple place. People here had blue work pants and wore a black sash instead of belts! The only people with belts were from the oil tankers, sailors, and they wore mother-of-pearl buckles with ships on them.

Society people went to Marchesa Gerini’s house, invited by her. They stayed at her house. She told me, “Look, these people come from big cities, you can’t imagine…” and it was true, until a certain age I never got out of this area, so I hadn’t seen big things. Gerini told me, “Here, it’s a whole different world. Here, it’s still a rural place.” Back then people in Porto Santo Stefano all had donkeys. You saw these little donkeys all over. In the evening, if one started braying, they all started braying! And the seafront drive wasn’t there yet. It was beautiful, the seashore was right there. In front of the town hall, there was a little beach.

At that time, the people just came. I got to the point that, in my store, I had a fridge with all the different brands of whiskey that they drank. They came to meet each other at my place. They spent money on stuff they would never even put on, what mattered was that they hung out there. These people came from elsewhere, the Marchesa sent them to us, because we had some pure silk that no one else had. In wartime, all of us were evacuated to Santa Fiora, and my parents had all this silk hidden in a walled-up room. After the war, we returned. This silk, I remember it, was stupendous. I mean the quality… I’ve never seen that quality again. It was so fine, exceptional. She sent us those people just for that. They looked around the town, the only clothing and fabric shop was ours. Ours and one other, which was a relative called Romolini who only sold fine linens.

Once Jerry Lewis came to the store, came right in. He had an interpreter. I didn’t understand a word of English. He looked here and there, he was all over the place, he was like a cricket. The interpreter said, “He likes that stuff there.” He didn’t even say “shirts.” It was a peasant shirt. One the farmers wore when they worked. It was double-twist cotton, herringbone, with different colored stripes. It had a collar, three buttons at the top and then a pleat. The farmers used to tuck it into their pants. It was made so if you bent over, it would stay in place. If it were made now, it would be better than many other shirts around. But he said, “Do you have a pair of scissors?” I said, “Yes, yes, but look, the shirt’s ready, there aren’t any uncut threads...” I thought maybe he was going to cut off the seamstress’ tag. At that time there was a paper tag with the name of the woman who made the shirt, which was lightly sewn in. But no…

“Excuse me, what’s he doing, ruining one of my shirts?” I asked. The interpreter said, “No, no. Look, this gentleman really likes the shirts, but he wants them without the collar. Just the neck band, and that’s all.”

“If that’s what he wants,” I said.

“Give me all the shirts you’ve got. He’ll take them,” he added.

I said, “I’ll give him the shirts, but the collar, you can cut it,” because if I had messed up…

So he cut them off.

What were some of the lessons you learned about selling to the jet set?

Since I already knew various people, I had begun going to Porto Santo Stefano. There was a beautiful elite of international people and I understood a bit their way of thinking. Marchesa Gerini instructed me in the ways of those people. She taught me that you cannot be timid with the rich; you have to act as if you are equals. Even if you are in your underwear, you have to be so confident that they will say, “Ooh, who is that in their underwear?”

Also, we were simple people, so we thought stuff had to be affordable, but Gerini said, “You have to hammer them with the price! These people are used to the big city, the big boutiques, a different world from the one you live in here.” You have to keep the prices high. If not, they would say to me “I bought this stuff… yes it’s beautiful, but can it really be high quality?” If they paid such a dirt-cheap price, compared to where they usually went, they would think it must be lousy stuff. Gerini told me, “You’ve got to grab the bull by the horns! Since they’re telling you that it seems too cheap, raise the price!” I raised the price, but it never seemed high enough for them. If my sister Roberta had been there, she would have skinned them alive!

After working with more traditional designs, how did you think of something as unusual as bell-bottoms?

Around 1960, we had a storage room full of needlecord velvets in every color that my father bought in Northern Italy near Milan. We wondered, “What can we do with all this colorful stuff?” Everyone wore gray back then after the war, until the 1950s. Gray and black, like now. It seemed like a world of undertakers!

Now, the woman who later became the model for the pants was good at painting. When these bell skirts, with tulle underneath and the big pockets on the front, came into style, she used to paint things on them, puppies, kittens. The skirts seemed to be made out of jute sacking. There was a period when they were in style. They had these big pockets and that shape, from there I had the idea—why not makes pants like that?

At the time, my sister Adriana never came in the store; she only came in when there was the representative of the Fontana Sisters. The Fontana Sisters had only started a few years before in Rome, and the representative was a gentleman from Bologna who brought outfits in the latest fashions. So, my sister was there that morning. I looked at my sister and said “Come here,” because she drew quite well.

“Come over here with me. With all this beautiful velvet, you know what I would do?” I said.

“Look, I want to take a wild shot. You know what it is? We do an extravagant pant! We make a low-waist pant, with the navel visible, for ladies. With two small pockets here, cut off, form-fitting but with flared bottoms.”

My sister thought about it and said “Well damn, that is a nice idea!”

So I went to the pattern cutter, a fellow called Ugo Cannone, who did the paper patterns for us. I explained to him, “Look at this fine velvet, which we have in all these vibrant colors, yellow, pinks, fuchsia, turquoise, sea green, beautiful.” He was a man of a certain age, a tall man, who handled the administration of the fishermen’s cooperative for the town of Orbetello. But he was also a tailor, and he was a good tailor.

I said, “Look, let’s do this pant.”

And he said, “Gee, it’s really nice.”

He also said, “Look, I may have a girl to base them on, the body of this girl here.”

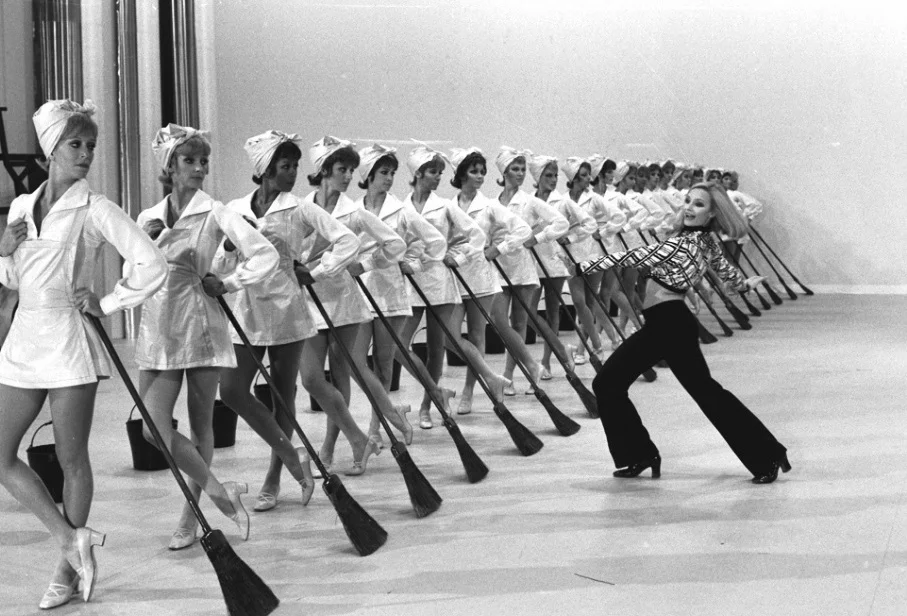

I said “Who, Cosetta?” I knew all the girls who worked for us. Cosetta had a really exceptional little body. A classic Mediterranean girl! So what did he do? He took all her measurements and he put it on cardboard and cut, and he made this pant. When we saw it, when she put it on, we were left with our mouths open. All the pants we made at first were that colored fine velvet. They weren’t so exaggerated, like they became later in the 1970s with the huge legs.

How did you introduce the pants to the market?

As I was thinking of Cosetta, I also began thinking of a person I had in mind in Porto Santo Stefano. There was an international elite, they started all those villas, wealthy people started to come, and there was the daughter of one of these people. There was this group of around 6000 well-off people who started trends, who brought things into style. I had a phone number, because she came to my shop to buy stuff. I telephoned her and she said, “What do you want?” I said, “Come, and I’ll give you a gift.” She came and when I took it out of the box, she was already going crazy for it. She went in the changing room and put them on. When she came out, it was as if I had sewn them onto her. They were perfect on her! But then, they were perfect on everybody. La Carrà (Raffaella Carrà, Italian singer and television host) all of them, Modugno (Domenico Modugno, Italian singer-songwriter), would come and stay at our place for the whole day. I even saw Carrà on RAI TV in one of our pairs of pants.

So I gave these pants as a gift to this girl; there were five pairs, turquoise, red, various colors. And I said, “If you take these to Rome and they see them on you,”—since I had understood that there was this circle, who all knew each other and so on—“it’s done!” And in fact, it took off, big demand, big demand, big demand. We were the only ones who sold them, only us. Nobody else had them. People were lining up for them. Even shop owners came to buy. They came from everywhere, from Rome. Word got around a bit that everybody liked those pants. That started the ball rolling.

How did you manufacture the pants?

At the beginning we made them ourselves, here in the workshop next door. Eventually, I had to do my military service. Luckily I had to, because otherwise I would have lost my mind. I had these women who worked for me, and I worked the whole day. I used to go to bed at three in the morning and I had to get up at six to pack up all the work they’d done. I did this for three or four years. I was going out of my mind, lucky I had to leave for the military.

When the demand for bigger volume came, we couldn’t keep up with it. So what did we do? With my dad, we thought, “What’s the biggest company around Firenze?” It was Migliorini e Tilli, who had one of the biggest garment factories. I think it still exists; at least until 15 years ago the son was there. It was one of the biggest pants makers around Firenze. We went to see him, we negotiated the price, my dad and I together. I was a bit shocked by a comment the Neapolitan pattern cutter made. Neapolitans are original, and a pant of that type, at the time, was original! For the time, after the war, everything gray, everything black, all that sort of thing. On the first ones done, my girls made a mistake, they did a man’s zipper, it was on the wrong side, on the side for men instead of women, because they sewed men’s pants. So this Neapolitan said “But then you have to tell me something. But, this trash, who are you going to give it to?” I said, “You think about cutting them well, then you’ll see who we’ll give this trash to.”

This Migliorini e Tilli, I had them do several thousand, without a pause.

How did you handle branding? Did you try to build a brand name that customers would want?

The first ones we did were with the DECA label because we already made men’s pants under the name DECA, from “Derna Casini,” my mother. It was the first company in the Maremma region of Tuscany that made garments, the first small business. As in fact we had the Necchi sewing machines, and when we were started doing pretty well, the Necchi rep said, “Casini, if you go to Brazil for us, Necchi will give you the machines free to launch them there.”

As long as we were making them, we put a tag with the name “DECA.”

After, when we had them made by someone else, the merchants started to come and buy them from us, from my mamma. So, what did we do at the manufacturer Migliorini e Tilli? For example, in Rome there was Bartocci’s store, called “Righetto,” but there were also other stores. In order that they wouldn’t compete with one another selling the same product, a different label was printed for each. But they were all made by the same place. You put a different tag, so the clients don’t know. This is the old trick, they still do it today. They can say “But it’s different, ours is better.” So they each put their own tag.

People didn’t buy them for the name anyway, they bought them for the style and the colors.

How long did the venture last, and how did it end?

So, what happened? After three years, this guy called us. By then they were even coming with trucks to load them up. The shop-owners came to us, everyone came to buy them. So many came, it was scary. This guy from Migliorini e Tilli came and said he wanted to talk, so I said, “Listen, sir, let’s talk with my father, and see what he says.” I thought, “Who knows what he wants to tell me?”

He said, “You have to do something big for us. Why don’t you let us license them and make them too?”

It turned out they thought that we had them patented! In reality, they weren’t patented at all. In fact, I thought about it after, because the companies around Florence, at that time more than now, everyone copied everything from each other. Then the man from Migliorini e Tilli just said “Well, I’ll do these pants too.” So the pants factory, which was one of the biggest, made these pants and started the ball rolling, and soon everybody had copied them and knocked them off. So it happened that everyone made them. Mind you, we’d already sold thousands and thousands of pieces, nothing to sneeze at!

And that’s how this pant was born, from a storage room full of velvet that we didn’t know what to do with, all colorful, the idea came to me to do a pant in that way. It came to me and it was exploited by others because we didn’t patent them. But this happened, this exploitation by the others, four or five years after we had started making them. We only thought that it would last two or three years, it would last a short time and it would end there. I thought it was contained. I thought, knowing these people who came to the seaside; they were wealthy people. I said, “It’s extravagant stuff, only they could wear something like that.” Who thought it would end up this way?

Why did it become so big? For the time it was a revolution, really a revolution, like going from black to white. You were coming from something completely different. Because there were kids, also in the big cities, that wanted to express themselves differently, but there was no outlet. I’m telling you, back then, anything you tried took off.

“Why did it become so big? For the time it was a revolution, really a revolution, like going from black to white.”

Those things to me were so beautiful; it was such a beautiful period of my life. What happened here in Argentario is something one can’t explain, because it’s something unimaginable, unrepeatable, something that will never happen again. Because, Porto Santo Stefano, the Argentario and Ansedonia, was, shall we say, preferred by all the high society that there was in Italy. With this Italian high society, there came also that from outside Italy. There was a mammoth turnover in business. Really, mammoth. I’ll give you just one example, there was someone from Santo Stefano, who cleaned gates—cleaned up and painted them—he did lawns here and there, and he bought a 26-foot powerboat! I did well too, with the little shop I had in Santo Stefano, after I fixed it up and so on.

We had the great fortune then that all the people who were able to, had a great desire to live. Whereas now, they all feel so desperate. Behind us, we had nothing at all. What we had was this: people who liked to live and knew how to live, people who liked to spend money.

What do you see as the essentials for the successful launch of a piece or line of clothing today?

You have to have a good idea, and follow that idea. Find a good pattern cutter. Make four or five high-quality pieces at most; don’t start with something too big that you can’t control. You have to know fabrics, and where to find them. You have to have to do high quality. And then work your ass off.

Everyone who doesn’t know materials, fails in the end. I learned about that from my dad. A young relative of mine wanted to make Italian clothing produced in China. They tried to do it but they didn’t understand anything about the material and they ended up with rubbish. I say, fine, send everything to China. All these Italian firms can produce low quality product in China, they can all compete with one another to make the cheapest. Meanwhile we can focus on making the best, because we know how to. There is actually less competition inside Italy now, with so much production in China. It hurts the Italian brand, but the high-quality stuff made in Italy stands out.

Do you have any plans in fashion now?

After the pants, we did well in wool sweaters and knitwear. We created the models and colors and produced them, then exported them to the US through different Tuscan brands. Fiorucci was selling this kind of sweater at 60 thousand lire at the time and we sold them at triple that price. We had to sell them under another brand, not our own, or people would have found fault with them. To make them, we had 500 women working at home with knitting machines, around the town of Magliano in Tuscany. I had to stop working with wool though. I became so allergic to something in it that I ended up in the hospital with an IV full of cortisone.

Now, I have had in mind certain things that I’m certain if I do them, they’ll take off. Like this thing that I had the idea for when I went to the luxury fairs. I have an idea for a dress shirt that could sell for 1000 euros a piece, all over. Knowing a gentleman who makes fabric in Prato, called Pecci, I would make a particular fabric that is no longer made. I told him the idea and his eyes popped open like an owl’s! Two or three styles, but a design that nobody has ever done before. I wouldn’t even make very many, just 1000 pieces a year, that you could do in two months of work. I don’t care how much I could make if I did more. I would be satisfied with that, I don’t want anything more. I’m like my papa, always a foot soldier, never a captain!

Conclusion

Regardless of the precise significance of Casini’s bell-bottoms, his story offers interesting lessons. What struck me was how it is equally a tale of business sense and fashion sense, both of which Casini acquired organically through his practical apprenticeship in the family business.

Casini started out with the challenge of finding a way to add value to a material acquired on speculation, by transforming it into a market-ready and easily salable product. His highly creative solution fit a niche, and went on to create a market with demand far beyond the original supply that motivated him.

The style’s diffusion and longevity in the 1960s and 1970s seem to stem from its ability to ride the wave of cultural changes of the period. Although it is a relatively simple design, it is clearly visually powerful. The bold, recognizable silhouette, which had been around for decades in various forms, lent itself easily to association with statements defined by the shifting cultural icons and movements that adopted the style. Casini clearly saw the potential local appeal of an “extravagant pant” that would let people express their urge to identify themselves with something new. In Italy, this may have started simply as the desire to live and enjoy life, but it evolved and expanded over time, carrying bell-bottoms along with it.

Notes

[1] Drowne, Kathleen Morgan, and Huber, Patrick. The 1920s, Greenwood Press, 2004.

[2] Wallach, Janet. Chanel: Her Style and Her Life, Mitchell Beazley, 1999.

[3] Halvorsen, David. "Fight For Bell-Bottom Pants." Chicago Tribune, November 17, 1963.

[4] Welters, Linda. Twentieth-century American Fashion. Oxford: Berg, 2005.

[5] Chenoune, Farid. Des Modes Et Des Hommes: Deux Siècles Délégance Masculine, Flammarion, 1993.