Ethel Traphagen: American Fashion Pioneer

It is hard to imagine a time when New York City was not a world fashion center, rivaling Paris, Milan, and London as the mecca of all things sartorial. But in December of 1912, when the New York Times announced the first ever American Fashion Contest, New York Fashion Week was but a twinkle in the American fashion industry’s eye. It was an eye that looked squarely to Paris, and Paris alone, for design inspiration. The contest was created in collaboration with Ladies Home Journal editor Edward Bok who had been promoting “American Fashion for American Women” in the magazine since 1910. Bok’s campaign was founded in the country’s unwavering dependence on Paris fashion, which American designers adapted and interpreted for the American market at all price points, from ready-to-wear to made-to-order, the result of which relegated the American designer to a place of anonymity and deemed their original contributions to fashion unworthy of recognition. Thirty-year-old Ethel Traphagen of Brooklyn, New York was one such designer until the New York Times contest pulled her out from under the shadows of Paris and thrust her into the national spotlight.

Ethel had worked in the fashion industry for almost ten years as a fashion illustrator, designer, and teacher when she won the coveted first-place “Evening Dress” award in the New York Times contest. A New York City native born in 1882, Ethel graduated high school and studied art at the National Academy of Design before embarking on her career in fashion in 1904. Her many employers over her formative years included Vogue and Dress Magazine (later Vanity Fair), Macy’s, Bloomingdale’s and Lord & Taylor, as well as the custom-import houses Thurn and Mademoiselle Jacqueline. At six feet tall, the red-haired, blue-eyed Ethel presented a striking presence with an ambition to match. In 1907, Ethel’s friend, artist and dancer Paul Swan, told some of their mutual friends: “You are stars—you merely twinkle. Miss Traphagen and I are comets—we shall leave a path in the sky.” [1]

After almost a decade in the industry, Ethel began to envision an American fashion system that worked independently of French influence. For her, education was key. Her own early career was fraught with difficulty and self-described “heart-ache” as she lacked any formal training and had to learn the trade through trial and error. In an effort to impart her knowledge and experience to future professionals, she took a series of teaching jobs beginning in 1911. By 1912, she was teaching at two schools and running the fashion design and illustration departments at two others.

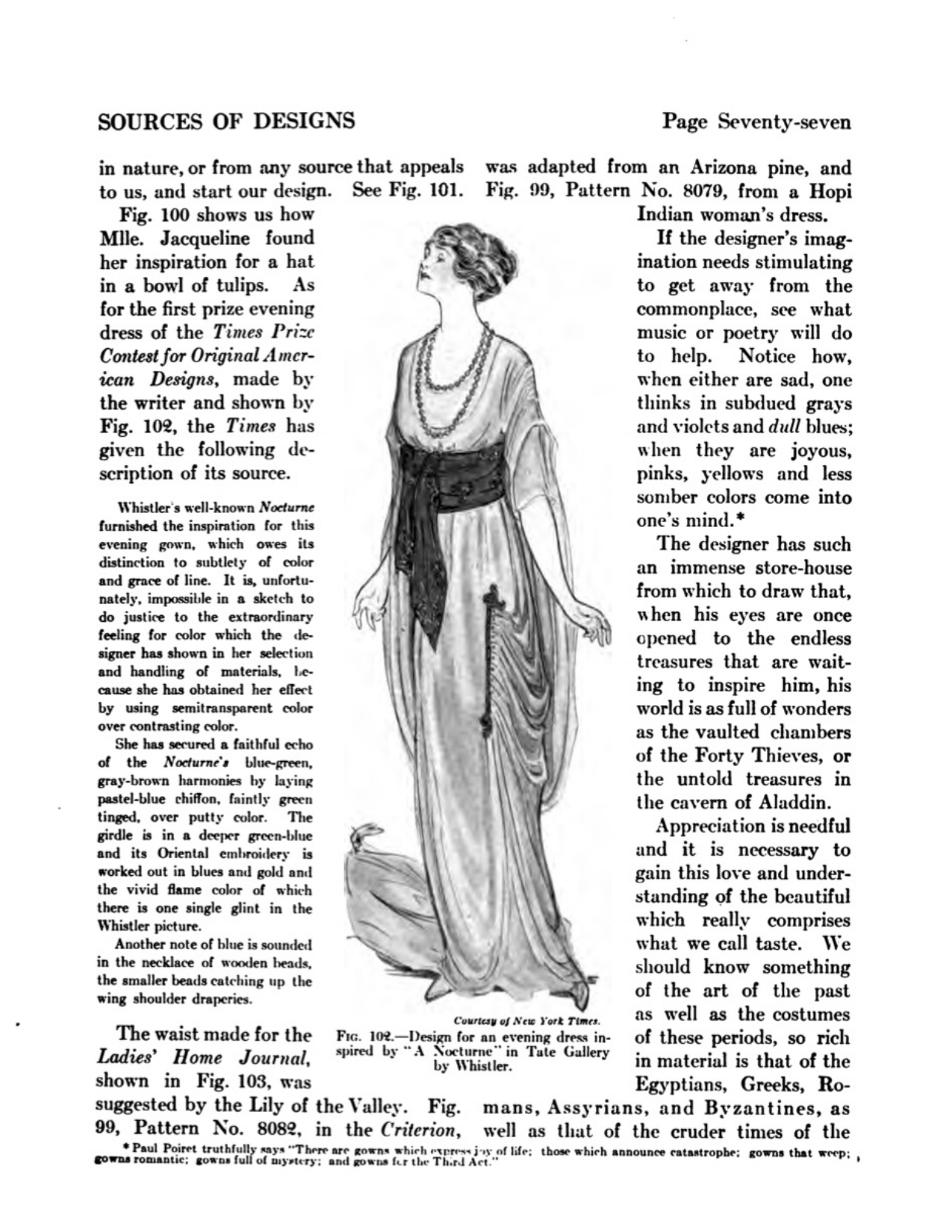

Design-by-adaptation was at the core of Ethel’s design and teaching methods. Interviewed by the New York Times in 1913 about her winning design, Ethel expounded upon her beliefs that original American design could be achieved by looking to art and fashion history as sources of inspiration. Ethel embraced these tenants in her winning dress design, which she based on the painting Nocturne: Blue and Gold, Old Battersea Bridge by James Abbott McNeil Whistler. “In its very architectural expression, the gown represents the piers of the bridge in the foreground of Whistler’s exquisite Nocturne,” admired the contest’s judges, “while in her use of the silvery gray putty color, the yellow beads, the restrained use of the effective red, she had worked out a perfect harmony of color with a decided artistic feeling and a marked cleverness of technique.” [2]

“After almost a decade in the industry, Ethel began to envision an American fashion system that worked independently of French influence.”

Throughout the 1910s, Ethel used her industry connections to bring nationwide attention to her students’ work and their illustrations were featured in newspapers and magazines across the country. In 1920 and 1922, Ethel organized and staged two Cooperative Fashion Exhibitions in conjunction with industry professionals. “Is America to have a fashion art?” asked one New York Times headline after the 1920 exhibition, “Display of Domestic Designs in Gowns, Coats, and Negligees Gives Promise for Future.” [3] The publicity and success of these ventures fueled Ethel’s determination and in 1923, she opened the Traphagen School of Co-operative Fashion (later Traphagen School of Fashion), one of the first schools dedicated solely to training students for professional careers as fashion designers and illustrators.

The school opened in a small room in the Bryant Park Studio Building at 80 West 40th Street, New York City, in September of 1923, with only seven students. [4] Under Ethel’s tutelage and constant promotion, the school grew and prospered—it relocated to bigger facilities twice within its first two years and finally settled at 1680 Broadway. [5] Initially, the school only offered courses in design and illustration, but by the early 1930s, it had expanded to include departments in Construction (1931), Theatrical Design (1932), and Millinery. There was also a Commercial Textile Studio (1932) and a Design Service—both marketed students’ designs to industry professionals that included Cheney Brothers, Warner Brothers, and the Cotton Textile Institute. [6] It was not uncommon for a manufacturer to purchase a student’s design after seeing it modeled in one of the school’s annual fashion shows.

The school’s facilities boasted a 7,000-volume library—with books on everything from fashion design and illustration, costume and art history, to original 18th and 19th-century periodicals—as well as a museum. Largely acquired by Traphagen herself, the Traphagen Museum’s collection was comprised of thousands of garments and accessories, ranging from the seventeenth-century to contemporary ethnographic materials. One of the highlights was a suit owned by the nineteenth-century Bavarian king Ludwig II, which was embellished with 80,000 pearl seeds. The school’s library and museum were direct manifestations of the design ideology Traphagen imparted to her students: design by adaptation. Ethel expounded upon the practice in numerous published articles throughout her career, as well as in her book Costume Design and Illustration, published in 1918 and reprinted in 1932.

Ethel’s quests for new sources of design inspiration for her students took her around the world. In 1928, she accompanied her husband, the well-known painter William R. Leigh, on an expedition to Africa and returned with a large collection of African chests, dolls, costumes, and jewelry. In 1929, she partnered with the textile manufacturer C.K. Eagle and Co. on an unprecedented campaign to market her students’ African-inspired textile designs to American consumers. “This was the first occasion on which there was a practical tie-up of inspirational design done in an American school with the manufacturer of textiles and the retailer,” wrote Ethel. [7] The designs were widely publicized in what came to be known as the “Zanbaraza” campaign and were sold in the department store Arnold Constable. [8]

In its January 1930 edition, the American Silk Journal featured pictures of the textiles in an article entitled “Original Motifs for Spring.” The article’s author heralded the Zanbaraza prints as “one of the most unique lines of silk prints ever produced in the United States,” and credited Ethel with starting a “major fashion movement”:

Ethel Traphagen… saw in this major fashion movement the beginning of the end of our habitual limiting of ourselves to the designs from Paris. To Miss Traphagen, a slavish dependence upon Europe for design was the most senseless and intolerable condition in current American art. [9]

Only one month prior to the article—and campaign’s debut—Ethel wrote a scathing letter to the editor of the New York Times entitled, “Fighting the New Fashions,” in which she lambasted the “French style factory.” In 1929, while Ethel was busy planning the Zanbaraza collaboration, American Vogue declared higher waistlines and longer skirts as the latest word in Parisian chic, shunning the shapeless shifts of the 1920s. In her letter, Ethel vehemently denounced the new Paris fashions and criticized American women for following them “sheepishly”:

One great good the World War accomplished was to free women from the curse of stupidity in the matter of clothes, and now comes this effort to set women back a century. These atrocities…are ground sweeping filth collectors, dragging the germs from the streets into the home and defeating the best sanitary efforts of the twentieth century. It is an everlasting shame that civilization has no adequate weapon to combat this many-headed beast—French fashion—that is trying to exercise a more complete tyranny than any monarch the world has ever known.” [10]

Ethel’s reaction was understandable, albeit a little extreme. She feared the new styles meant a return to oppressive fashions that harkened back to the 1900s when women, including herself, wore restrictive steel-boned corsets to achieve the fashionable silhouette of the day. Ethel greatly valued the comfort and simplicity of the “simple corset-free costume” of the 1920s, which she considered “the best that women had worn during civilized history.” [11] To Ethel, the longer skirts were not only unsanitary, they were obstructive to women’s freedom of movement in the busy modern world, a world that she herself navigated on a daily basis.

Ethel was the epitome of a modern woman. A photograph from 1921 that accompanied an article that appeared soon after her marriage to her husband captured the pride of a woman confident in herself and her independence. The statuesque Ethel is pictured wearing a safari suit, complete with trousers—one of the many ways she defied traditional gender roles. The article was entitled “Lives Next Door to Hubby: Artist Bride Tells Why,” [12] and highlighted Ethel as the pinnacle of feminist virtue—she and her husband lived in separate but adjacent residences and she maintained her maiden name in public because of its association with her successful career. Much later in her life, Ethel’s adoption of trousers in the 1910s and 20s would earn her the title of the “Woman who Pioneered Pants.” [13]

In a 1932 New York Times article entitled “See Fashion Centre Moving to America—Miss Traphagen Says Transfer from Paris Logical—Nation Prepared for Change,” Ethel once again expressed her confidence in American designers: “Once awakened, America will show her capacity for organization and American designs and American designers will be accepted and featured as they should be.” [14] Unapologetically outspoken and passionately determined, Ethel’s tireless advocacy for American designs contributed to their recognition. When American designers finally won public acceptance and respect in the late 1930s and during World War II, the Traphagen School of Fashion was New York’s leading fashion institution. In 1941, New York Times fashion editor Virginia Pope declared New York City the “Fashion Center of the World.” [15] Ethel had found validation.

To celebrate the advancement of American fashion designers to a place of recognition and respect, Ethel began the publication of the Fashion Digest in 1937. A groundbreaking publication, the quarterly subscription magazine was dedicated exclusively to American fashion with an emphasis on past and present Traphagen students. As editor and publisher until her death in 1963, Ethel’s influence was strongly felt throughout the pages infused with fashion, costume, art, poetry, history, and even astrology. The Fashion Digest is key to solidifying the far-reaching success of the school and Ethel’s efforts throughout the years, as it featured the names of students who went on to achieve huge success in the fashion industry. Traphagen alumni include many of America’s most celebrated fashion designers such as James Galanos, Mollie Parnis, Vera Neumann, Geoffrey Beene, and Anne Klein.

“Her efforts were undoubtedly instrumental in bringing the work of American designers to the fore, her legacy alive and well in today’s thriving American fashion industry.”

Ethel Traphagen died on April 29th, 1963 at the age of eighty years old—fifty years after she won the New York Times contest and forty years after opening her groundbreaking school.[xvi] Tens of thousands of students from around the world attended the Traphagen School of Fashion before the school closed its doors in 1991, sixty-eight years after it first opened. The school’s success throughout Ethel’s lifetime and long after are a testament to the power of one woman’s unwavering vision and hard work. She was responsible for training a new generation of American fashion designers and industry professionals at a time dominated by the dictates of Paris fashion. Her efforts were undoubtedly instrumental in bringing the work of American designers to the fore, her legacy alive and well in today’s thriving American fashion industry.

Today, Ethel’s name and contributions have all but fallen into obscurity—the prolific school forgotten in the face of other successful institutions that continue to thrive, such as the Fashion Institute of Technology and Parsons School of Design. Thanks to the proliferation of digitized newspapers from across the country, Ethel’s far-reaching influence—in a career spanning almost sixty years—can again be brought to the fore. No longer forgotten, Ethel can now be recognized as the pioneer of American fashion design that she was.

Notes

[1] Janis Londraville and Richard Londraville, The Most Beautiful Man in the World: Paul Swan, from Wilde to Warhol (Nebraska: Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska, 2006), 57.

[2] Ibid.

[3] “Is American to Have a Fashion Art? Display of Domestic Designs in Gowns, Coats, and Negligees Gives Promise for Future,” New York Times, July 18, 1920, 76.

[4] Ethel Traphagen, “The Background of the Traphagen School,” in The Silhouette, ed. Ethel Traphagen, (New York: Traphagen School of Fashion, 1933), 8-9.

[5] Traphagen, “Background,” 9.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ethel Traphagen, “The Zanbaraza Prints—1929,” The Silhouette, 90-91.

[8] The campaign took its name from Zanzibar, Africa and “bazara,” a Swahili word for fair or fête. “Original Silks for Spring,” American Silk Journal, January 1930, 103.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ethel Traphagen, letter to the editor, “Fighting the New Fashions,” New York Times, Nov. 3, 1929, E5.

[11] Ethel Traphagen, “The French Fashion Factory,” North American Review 229, no. 1 (January 1930): 19-22.

[12] Margery Rex, “Lives Next Door to Hubby,” Sandusky Register, Oct 30, 1921, 1.

[13] Guy Pauley, “Woman Who Pioneered Pants for Women Sometimes Sorry She Did,” Marysville Journal Tribune, April 27, 1960, 13.

[14] “Sees Fashion Center Moving to America,” New York Times, October 16, 1932, F9.

[15] The outbreak of World War II in 1939 marked a significant shift in the fate of the American designer who, having continued to operate in the shadow of Paris throughout the 1930s, was suddenly left to stand alone. During the German occupation of Paris from June 1940 to August 1944, many of the leading fashion houses were forced to close, and those that remained open did so under severely limited operations. Communication with America was broken. Virginia Pope, “New York: Twofold Fashion Center,” New York Times, January 5, 1941, 8.

[16] Obituary, “Ethel Traphagen Leigh is Dead; Founded Fashion School in ’23,” New York Times, April 30, 1963, 34.