Safe Spaces of Desire: Advertisements in the Nineteenth-Century Fashion Press of Berlin, Paris, and New York

Although the nineteenth-century fashion press began as a national product, it soon grew to become an international phenomenon made possible by innovations in printing practices as well as travel and transportation. Regional and country-specific publications no longer operated within national borders. Once industrialization improved the process of moving people and ideas from place to place, the fashion industry — and by proxy the fashion press — elevated its practices to participate in an international dialogue with cities such as Berlin, Paris, and New York leading the way. The fashion journals originating in those metropoles reached female readers all over the world as evidenced by subscription data and reader letters sent to the editors. Toward the end of the century, advertisements were introduced and changed once more the role of the fashion press. From regional to international to consumer-driven publications, the fashion press continued to reinvent itself in an effort to stay current and relevant (attributes paramount to any successful fashion industry). Because these publications were written for women, it makes them particularly relevant to any study of the period grounded in a feminist methodology.

This essay looks at Der Bazar Illustrirte Damen-Zeitung, La Mode Illustrée, and Harper’s Bazar—fashion journals based in Berlin, Paris, and New York respectively, and more specifically the advertisements that appeared in them toward the turn of the century and which touch upon the intersections of material culture, consumption, and gender. While in some ways the fashion industry participated in the perpetuation of normative gender roles, in other ways it is also possible to witness a more subversive counter-narrative taking shape. Since these magazines were written for a female audience, I argue that they served as a “safe space” for the exploration of topics, ideas, and products that directly impacted women’s lives. As a result, these advertisements can be read as utopian spaces offering glimpses of a more egalitarian world accessible through the power of consumption. Part One of this essay offers a contextual overview of Der Bazar Illustrirte Damen-Zeitung, La Mode Illustrée, and Harper’s Bazar to highlight how these three journals in particular were participating in an international dialogue on fashion, gender, and consumption. Part Two turns to the advertisements introduced at the end of the century, which I argue play a critical role in demonstrating how womanhood was understood at the time. Not only are the advertisements revelatory of a gender and class discourse dominant at the turn of the century, they also hint at a fissure in that dialogue. Cultural change was on the horizon and hints of a new gender ideology aided by a burgeoning market economy unveiled itself in the tiny advertising squares present in the fashion press. Part Three explores the possibility of these ad squares as utopian in that they offered readers a way to greater gender equality, freedom, and independence via the consumption of the product or service sold. Although that egalitarian dream demanded a certain level of wealth, it nonetheless fulfilled the role of a utopian fantasy in that it allowed readers to imagine or believe themselves into a ‘better’ future even if they could not afford it yet.

A brief note on the media studies methodology I employ: There are several ways to read magazines as cultural artifacts. In her 2003 study, Understanding Women’s Magazines. Publishing, Markets and Readerships, Anna Gough-Yates argues that magazine analysis is still a relatively new field. [1] It was not until the mid-twentieth century that this medium gained scholarly interest. Early historians and literary critics took the approach of reading magazines for the instructions and “messages” they offered readers. They were read and studied like conduct books—as though the content within was taken at face-value by the readers who consumed those journals, using them as a map for how to perform their status, class, and gender. Later scholars adopted a reception based approach and looked for external cues to better understand how magazines were carriers of cultural meaning. Who published these journals and how were they distributed? Who had access to them and how were they consumed? A reader reception methodology takes into account the systems of production but does not look as closely at the content in favor of the meta-data. More recent approaches in media studies have addressed this gap by focusing on representation: are the images presented in the popular press representative of the reader or rather idealized products resulting of a particular time, place, and context? Who actually sees herself mirrored in the popular press? Are the images subversive or normative?

My study of the advertisements in Der Bazar, La Mode Illustrée, and Harper’s Bazar is influenced by this form of representation theory as well as reception theory: I consider the appeal of the advertisements (i.e., the intended message) and the assumed audience, but also search for additional indicators to understand how these ads represented the reader likely to have encountered them. For example, did a reader see herself reflected in the images of women holding elegant fans and wearing elaborate gowns? Or was she seeking the guilty pleasure of losing herself in a fantasy that would likely never mirror her lived experience? Moreover, I analyze these advertisements as a conglomerate and read the individual advert against the backdrop of all the other advertisements placed around it. By reading these ads as a whole rather than as individual messages neatly sectioned into separate squares we are better able to arrive at our point of departure: reading these ads from a distance that allows us to see them as pieces of a whole; as both prescriptive and descriptive, and as suggestive of a more complex narrative regarding the intersection of gender, class, consumption, and fashion.

Part One: Three Sister Magazines

Der Bazar, Illustrirte Damen-Zeitung was founded in 1855 in Berlin by the Louis Schaeffer Publishing House and published weekly for nearly eighty years. Not long after its inception, the magazine found a far-reaching audience and its distribution numbers reached 100,000 issues weekly as early as 1863. [2] By 1869 Der Bazar announced its goal to function as a “Weltblatt” (global publication) with a “Weltruf” (global reputation); its international influence was soon evidenced by the letters from readers and subscribers featured in the editorial columns. Subscriber letters came from all over the Western world: Berlin and other German cities, but also Prague, Paris, New York, Vienna, St. Louis, Chicago, and other international metropoles. Not surprisingly, other major cities soon recognized the earning potential of sister publications – first in Paris and later in New York.

Five years after the creation of Der Bazar and seven years before Harper’s Bazar, La Mode Illustrée, Journal de la Famille, was founded and published in Paris by a female editor named Emmeline Raymond, who ran the magazine until her death in 1905. The French magazine mirrored Der Bazar in content and layout, often printing the same images on the corresponding issue in Paris as the German version hit newsstands in Berlin. One such example can be found with the January 1878 cover of both magazines, featuring an image of two women roller skating while several children look on. Two issues later we see once again the identical illustration (two women in conversation in front of an oversized bookshelf) on both the German and French cover pages. These examples indicate that the two publishing houses were in communication and content traveled between the two cities for the planning and editing of each magazine. [3] A further link ties the two European journals together—both papers played a key role in the formation of Harper’s Bazar in New York seven years after the creation of La Mode Illustrée. Harper’s Bazar was directly and explicitly modeled after the German Der Bazar, even using a nearly identical name with an American spin to it, likely aiming to appeal to readers’ recognition of the Berlin publication which by this point was being translated into several languages and distributed in America as well as Europe. Harper’s Bazar was also marketing-savvy enough to employ Emmeline Raymond—editor of the French La Mode Illustrée—to serve as the American magazine’s Paris correspondent.

Harper’s Bazar first went to press in 1867 and, in another attempt at keeping with the successful model already in place in Europe, the publishers hired a female editor to run the magazine at a time when this was rather rare. Mary Louise Booth, who oversaw the magazine until her death in 1889, was the long-standing manager (mirroring Mme Raymond’s long-time tenure as editor of La Mode Illustrée) ofHarper’s Bazar. In her work Victorian Fashions and Costumes from Harper’s Bazar, 1867-1898, Stella Blum writes, “according to [Harper’s Bazar’s] first editorial, its aim was to be a publication which would combine the useful with the beautiful. Although it would include everything that would be interesting to the family circle, it was largely intended for ladies.” [4] The magazine recognized from the outset that women were the primary consumers and the obvious target audience for a magazine featuring domestic goods, fashion, and material items of all sorts ready to be acquired.

The editorial continued to explain that “special arrangements have been made with leading European journals, particularly with the German Der Bazar whereby Harper’s Bazar would receive fashion designs in advance and publish them at the same time that they appeared in Paris, Berlin, and other European cities.” [5] It was with this vision of keeping with or better yet staying ahead of the times that Mary Louise Booth ran the magazine. [6] Her keen editorial sense and innovative planning also led to advertisement space finding its way into the pages of Harper’s Bazar. Thus, while the American publication came to press as a result of the European models already in existence, when it came to advertisements, it was Harper’s Bazar that was the trailblazer.

By 1876 Harper’s Bazar featured multi-page advertisement sections hinting at what was to follow in Der Bazar just half a decade later. By 1881, Der Bazar introduced advertisements that grew in multitude with time, and finally, by 1889, La Mode Illustrée followed suit. In a way it should come as no surprise that all three magazines would incorporate advertisements once the practice reached the popular press. After all, the word bazar in the titles of both the German and American journal suggests a product that serves as a virtual marketplace. The images and texts within these publications were meant to incite desire and consumption. The purchasable items were brought right into the reader’s home paving the way for the fast fashion and disposable goods industries we now know today.

Part Two: A Virtual Marketplace

A cursory look at the three magazines of this study would suggest a fashion press that participated in the perpetuation of normative gender roles and hegemonic discourses. Women were portrayed as mothers, wives, and caretakers of the home. They were pictured indoors surrounded by domestic goods or outdoors on genteel promenades. Embroidery sheets, musical scores, poetry, and serialized fiction were a standard component of every issue. Detailed instructions on creating elaborate hairstyles as well as dispatches from Paris and London on the latest fashion trends demonstrate a preoccupation with the physical and aesthetic body. Yet every so often, a more critical inquiry about the role of women in society (such as an 1870 article in Der Bazar arguing for an ethical imperative to educate women as doctors) disrupts the typical discourse and destabilizes what appears to be a hegemonic construct of femininity within the safe confines of the home.

The advertisements functioned in a similar way: for the most part, they participated in the regulating of gender roles by creating a market economy based on gender difference: women were sold home goods and fashion items. They were offered silks, corsets, elaborate footwear, and ivory hair combs. A typical selection of advertisements across all three journals would include fashion items, services offered — such as lending libraries, musical lessons, and advice on losing weight — and an assortment of medicines such as ointments, pills, and syrups to cure anything from indigestion and headaches to speech impediments and dental troubles. A typical advertisement page in La Mode Illustrée in 1897 includes an ad for a corseting company, a weight-loss product “pour maigrir”, a cure for wrinkles, and a number of tonics promising to cure indigestion, dental troubles, and hair loss plights.

While there is nothing revolutionary about these products, the shift to identifying women as consumers with purchasing power and agency was itself novel and progressive. It also set the stage for what I identify as more transgressive and utopian advertisements for products that engaged with what it meant to be a woman and to be moving through the world in a female body. These slightly more infrequent advertisements tackling complex questions about womanhood— whether intentionally or not—hint at a dialogue starting to take place in society at-large. Their appearance in the fashion press and the framing of them as being “for women only” suggests that these journals operated as safe spaces for probing uncomfortable subject matters and destabilizing normative narratives within the realm of a smaller and more sympathetic market audience.

For instance, a number of advertisements addressed women’s bodies, hygiene, and sexual activity. One 1898 advertisement in Der Bazar (which appeared in multiple issues of that year) offered the reader an innovative device called a “Sitzdusche,” or a shower-like object intended to cleanse a woman’s lower body without requiring her to fully disrobe. In fact, the advertisement’s appeal rests on the assumption that a woman might need to use this quickly and effortlessly at any given time; it simply required two bucket-fills of water and presumably some level of privacy. As Michel Foucault has argued in The History of Sexuality, nineteenth-century Victorians were not prude or willfully ignorant of sexuality; rather, they developed an entire system of codes to talk about the very thing that one could not discuss openly. [7] That discursive play is evident in these advertisements that only hint at the uses and functions of these products that are for a women’s “private” use. What we see here, however, is an important shift in identifying women as agents of their bodies and sexuality rather than passive recipients of male sexuality.

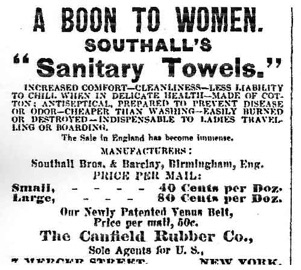

In a similar vein, an 1894 advertisements in the American Harper’s Bazar offers a product sure to improve a woman’s well-being as well as her ability to move through the world unencumbered by her physicality. It reads: “A Boon to Women. Southall’s Sanitary Towels. Increased comfort—cleanliness—less liability to chill when in delicate health—made of cotton; antiseptical, prepared to prevent disease or odor—cheaper than washing—easily burned or destroyed—indispensable to ladies traveling or boarding.” [8] In that little square of newsprint, we find one of the first examples of a women’s sanitary napkin ad—one which promised the female reader relief and freedom from that monthly ‘burden’ that her biology placed on her. Not only freedom at home but, perhaps most importantly, freedom outside the home as well as an improved ability to travel and access public and male-dominated spaces. Not surprisingly, this type of product emerged right as cultural shifts allowed for women to access the public realm with much greater confidence and regularity. Around this time, the concept of the flâneuse appeared (the female version of the well-recognized flâneur, moving through urban spaces ease and ample time). By the late nineteenth-century, women were much more active agents in public spaces contributing to the shaping of social and cultural discourses, impacting the economy, and the redefining public-private boundaries. [9]

Advertisements such as these above-mentioned ones demonstrate the shift in both ideology as well as women’s lived experience as impacted by her gender role and biology. The social changes ushered along by women’s rights activists in the Western European world as well as in America are offered here to the average reader of mainstream fashion magazines in small, digestible units. These were not political newspapers nor did they emerge out of the fervor of the women’s movement that produced a number of publications calling women to revolt and demand increased access to the public realm that regularly excluded them. Der Bazar, La Mode Illustrée, and Harper’s Bazar were mainstream in that they followed the models of home goods and fashion publications present on the market before, concurrent with, and after their publication tenure. These journals did not profess allegiances to any given ideology or political movement and they, for the most part, followed the traditional script of fashion magazines identifying a woman’s realm as the aesthetic and domestic. Yet even within these spaces, we see that destabilizing of traditional norms and a willingness to engage with subjects that cross into the realm of women’s rights and modernity.

One other such example is found in the 1889 advertisement for bicycle tires in the German Der Bazar. A large-scale and imposing ad with minimal text draws the viewer’s focus onto a simple yet stunning illustration of a woman in movement. She appears to be nearly in flight—her body bent dexterously over bicycle handles, tilted ever so confidently to the right as though making a tight turn in the road, hair flowing carelessly in the breeze. Similar to the previously mentioned ads, this particular advertisement is about so much more than the rubber tires it is offering for sale: it represents freedom, movement, independence, and joy. While it would still have been coded as masculine and unbecoming of a ‘lady’ to ride a bicycle, many women did ride bikes and that the gains made from this simple machine were manifold: fashions changed to allow for this mode of transportation (the billowing skirts and crinoline dresses that hindered mobility would no longer do) and women began to gain access to spaces previously remote and unreachable. With the use of a bicycle, a woman could travel farther, taste independence, and learn to trust her physical abilities. Scores of books have been written on the subject of the bicycle as the harbinger of women’s emancipation from the historical perspective available to us today. [10] Here we see how this object was introduced to the contemporary woman in a way that hinted at what we today recognize as the revolutionary power of the bicycle.

In all of these examples we see an emerging narrative defining utopia as a place where women had greater physical and geographical mobility made possible by the consumptive powers of the reader and buyer. Yet to what extent could the average reader afford these products? Was she as wealthy as the women often pictured within the fashion press—women dressed in lavish gowns and surrounded by elegant interiors? A further look at the classified ads, particularly the ones found in the German Der Bazar, hint at a more complex reality assumed of the average reader.

Part Three: Fantasy vs. Reality

One could claim that the readers of these magazines were the type of consumer who could afford costly corsets, ornate hair combs, and sojourns in the countryside for spa and beautification treatments. And perhaps some of the subscribers did meet that profile of the ideal reader and consumer willing to open her pocketbook to whatever the advertisements suggested. I argue, however, is that these advertisements functioned much like marketing practices today: as images and fantasies offered to regular housewives who yearned for the space and tools with which to craft their fantasies of a better, easier, more beautiful life. Not coincidentally, the offers for beauty products are peppered between advertisements for indigestion cures and migraine pills. One advertisement promising to cure even the most stubborn of migraines shows a concerned wife poring over her suffering husband trying to ease his pain. As keeper of the home and domestic sphere, the woman in this ad, much like the average reader, likely had to play the role of mother, nurse, and caregiver not only for her children but spouse and extended family as well. Corsets, stylish shoes, and face tonics aside, hers was a life that required hard work, compassion, and exactitude. She arranged her children’s days and provided for all the things within the home, including the medical needs of a family that likely could not afford to seek a physician for every small discomfort.

Another clue comes in the form of marriage and employment ads. This formulaic approach was found in several issues of the German journal throughout the 1880s: a wealthy businessman, usually widowed, with a modest fortune, eager to find a mother and caregiver for his children, is looking to marry a girl “from a good home.” [11] While the lavish Parisian fashions and luxury household goods would suggest a reader of upper-middle to upper class, the advertisements appealing to single girls of modest means looking for employment or marriage paints another picture altogether. We see in these pages a multidimensional female reading population that likely included women of older generations whose lives were still largely centered around the domestic and the family. Yet we also see an appeal to women looking for self-sufficiency, for greater mobility along geographical as well as social plateaus, and for inclusion in the public realm previously and largely inaccessible to women.

Justine DeYoung writes about the fashion journals of Paris in the nineteenth-century, specifically La Mode Illustrée, as functioning as a how-to guide for the bourgeois reader eager to learn the language of clothing to better communicate – or perhaps pretend – status, class, and wealth. DeYoung writes, “previously, the relative quality of a dress’s fabric and the chicness of its cut had been thought sufficient to reveal the status of the wearer, as only the wealthy could afford to buy costly fabrics and to update their wardrobe frequently.” [12] DeYoung argues that fashion magazines took up the role of being sartorial dictionaries of sort, allowing readers to decipher nuances in dress and taste. As Fred Davis has argued, the nineteenth-century and the industrial revolution not only brought with it the mass reproduction of material goods and ready-to-wear fashion but also introduced the average consumer to the personal sewing machines that allowed for trends and clothing styles to be reproduced at home for a fraction of the cost of the original. [13] Now more than ever, fashion magazines proved indispensable as guides for navigating a changing social order while allowing readers to not only experiment with the old and revamped but also the new and never-before-seen. As noted, the advertisements sections of these journals functioned as a particularly active space for exploring the newer and more boundary-pushing aspects of nineteenth-century fashion and material culture.

Conclusion

Women’s publications have long occupied a particular place in the reading public. Often dismissed as inconsequential and without much substance, it was (and still is) not uncommon to see these texts ignored by any consumer other than the female reader specifically addressed by them. In nineteenth-century Germany women’s texts (which included texts for women as well as by women writers) were termed “Trivialliteratur” (trivial literature) and dismissed as a cute and entertaining exercise in personal expression that was not too far removed from what a woman might compose in her diary or letter to a friend. Not surprisingly, many women opted for male pen names and searched for ways to put forth their works without their sex getting in the way. In France, the second wave feminists of the 1970s responded to the historic dismissal of women’s texts by reclaiming the art of “writing like a woman” and coining the term “écriture feminine” (feminine writing). [14] While the reclaiming of narratives produced by women and the promotion of women’s writings as relevant and noteworthy because of the specific lens used in producing those works allowed feminists to advance women’s role in the literary world, it came with unavoidable limitations. Once again, women’s works and works for women were treated as coming from a particular niche point and made palatable to a specific minority audience.

Today in America, for instance, we talk about “chick lit” as the texts written by women for women. We also talk about “mommy bloggers” when online content is written by women and deals with topics that continue to be coded as feminine, such as marriage, parenting, domesticity, and aesthetics. When men blog about these topics, rarely do we see the term “daddy blog” being applied; they are simply blogging. Chick lit and mommy blogs, like their predecessors Trivialliteratur and écriture feminine, limits writer’s access to mainstream publishing and puts brackets around texts using female voices as the I-subject.

In general, these practices are damaging and isolating. Women’s words, texts, publications, and lived experiences are marginalized and ushered to the periphery. Yet in these three women’s journals we see something that challenges the notion that “for women only” texts are inheritably oppressive. Here we see the possibilities offered by texts assumed to be read in private and by certain groups: they allow for taboo topics to be explored and for novel ideas to be introduced. They address themes that are perhaps to incendiary to make it into mainstream publications and they offer sympathetic voices that perhaps mirror a reader’s lived experience or offer her the fodder for daydreaming that only a magazine written for that particular audience can do. In that regard, these publications played the critical role of creating utopian spaces moving readers from their daily reality into spaces full of excitement and potential.

Notes

[1] Anna Gough Yates. Understanding Women’s Magazines. Publishing, markets and readerships. NY: Routledge, 2003.

[2] Not only did Der Bazar reach popularity quickly within the German speaking world; by 1861 it was already being translated into French and Spanish for international distribution. Andreas Graf, Die Ursprünge der modernen Medienindustrie: Familien- und Unterhaltungszeitschriften der Kaiserzeit (1870-1918). Ablit: 2007. http://www.zeitschriften.ablit.de/graf/ 42.

[3] I have also found several articles reporting on French culture and customs published in Der Bazar signed with the initials E.R. – could these have been contributed by none other than the famed Emmeline Raymond, editor of La Mode Illustrée? Moreover, Mme Raymond was born to a German mother and grew up connected to her German ancestry and language. She also printed translated short stories by the well-read German writer E. Marlitt, who became a national sensation when her works were printed in the German best-selling family magazine Die Gartenlaube.

[4] Stella Blum, Victorian Fashions and Costumes from Harper’s Bazar, 1867-1898. (New York: Dover Publications, 1974), v.

[5] Ibid. Emphasis mine. The relationship between these three major fashion publications highlight the increasing internationalization of the press and fashion industry at the time. The use of shared content as well as the American dependency on European dispatches on fashion and consumer goods highlights a complex and intertwined system of communication that was not linear, chronological, or predictable.

[6] It was only Mary Louise Booth’s death that Harper’s Bazar changed ownership and in 1902 also updated the spelling of the magazine’s name to what we know it as today: Harper’s Bazaar. While I have not found in my research any explanation for the change in spelling of the magazine’s name, I would argue that it points to a commitment for the publication to stay current and relevant. The change from writing the word “bazar” as “bazaar” with two a’s was something that occurred around the end of the century and it is likely that the magazine followed suit as a way to look modern by shedding the antiquated spelling of the word in its name.

[7] Michel Foucault. The History of Sexuality. Robert Hurley, Trans. Pantheon: New York, 1978. 11.

[8] Harper’s Bazar. September 1887. The Museum of Menstruation and Women’s Health. http://www.mum.org/southall2.htm

[9] Aruna D’Souza and Tom McDonough’s edited anthology The Invisible Flâneuse? Gender, Public Space and Visual Culture in Nineteenth-Century (2006) is a wonderful resource on the emergence of the flâneuse and the role of women in public spaces. More recently, Laura Elkin has taken up this subject and explored the lives of famous flâneuses such as George Sand and Virginia Woolf in her 2017 work Flâneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris, New York, Tokyo, Venice, and London.

[10] See Sue Macy. Wheels of Change. How Women Rode the Bicycle to Freedom. New York: National Geographic Children's Books, 2011. Also: Nicholas Oddy. “Bicycles.” The Gendered Object. Ed. Pat Kirkham. New York: Manchester University Press, 1996, 60-69.

[11] One such example is found in Der Bazar, Illustrirte Damen-Zeitung, April 1881. The original reads: “Ein Wittwer, 40 Jahre alt, Familie 2 Knaben, dessen Berufsthätigkeit ihm keine Gelegenheit zu Damenbekanntschaften giebt, wünscht sich mit einer Dame aus guter Familie zu verbinden. Ein liebesvolles Gemüth Hauptsache, Vermögen nicht erforderlich.“ Translation: Widower, 40 years of age, with a family of two sons, with a profession that does not offer much opportunity to make acquaintance of ladies, is seeking a lady from a good family. Most important is a kind disposition, fortunate not required.”

[12] Justine DeYoung, “Representing the Modern Woman: The Fashion Plate Reconsidered (1865-1875).” In Women, Femininity, and Public Space in European Visual Culture, 1789-1914, edited by Heather Belnap Jensen and Temma Balducci. Ashgate, 2014, 99.

[13] Fred Davis, Fashion, Culture, and Identity.U Chicago Press, 1992.

[14] See Hélène Cixous, “Laugh of the Medusa.” Keith Cohen and Paula Cohen, Trans. Signs. 1:1976. 875-893.