Points of Touch: Towards a Fashion Epistemology

The following essay emerges from Marco Pecorari's doctoral dissertation, Fashion Remains: The Epistemic Potential of Fashion Ephemera, and forthcoming book of the same name. A version of it also appeared in the pamphlet created for the exhibition "The Ephemera of Fashion" held at the 2016 Hyères Festival and curated by François Cam-Drouhin.

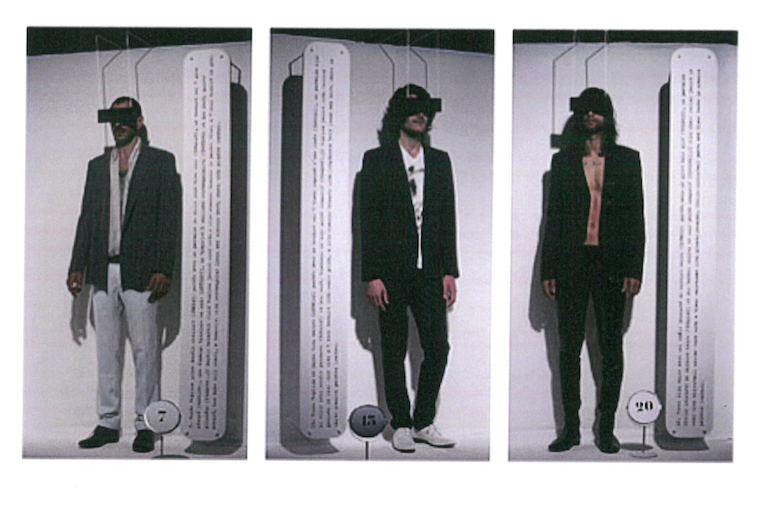

For its s/s ’09 menswear show, Maison Martin Margiela replicated the appearance of a life-size catalogue. Standing in front of oversize white panels recalling the maison’s iconic accordion-shape catalogues – complete with type-written descriptions and the garment numbers – models posed behind black, rectangular panels that obscured their eyes, recalling the famous Incognito images in which black bands were drawn over the eyes of the models’ eyes. Transforming the show into a “living catalogue,” Margiela inverted the mechanics of the presentation of a collection whereby the latter became protagonist and not anymore a paratextual support to the show and/or collection. While this decision once again manifested an attempt to disrupt fashion practices by the Belgian brand, it also acts as a tribute to catalogues and ephemeral materials at-large. It speaks to their scope in the ways fashion is presented – to their being tools through which fashion is known.

“It speaks to their scope in the ways fashion is presented – to their being tools through which fashion is known.”

While garments, shows, shops, and magazines have (rightly) been at the center of attention in the study of spaces in which fashion is materialized, too often less celebrated materials - like catalogues, invitations, press releases, backstage passes - have been relegated to function as supportive devices in the study of fashion, without being looked at as objects worthy of study in their own right. This is indeed the case of those fashion ephemera that are often the result of both economic and creative investment but are, however, often thrown away. The outcome of durative collaborations between fashion designers, fashion photographers, graphic designers, art directors, make-up artists or models, these ephemeral materials circulate within private channels of distribution and take multiple and extravagant formats. The catalogue of Yohji Yamamoto's autumn/winter '86-'87 took the form of an un-foldable book portraying the Italian artist Luciano Castelli wearing Yamamoto's creations while painting. Angelo Figus's autumn/winter '02-03 invitation took the shape of a vinyl record, whereas Maison Martin Margiela's invitations have variously taken the shape of a dish, a laser-pointer, and a calendar. Prada's press releases for spring/summer '92 were written by the visionary fashion writer Anna Piaggi while Bernhard Willhelm's spring/summer '03 press release included poems and short stories in the presentation of the collection. Despite their peculiar nature, these types of objects have often been used as documentary sources and have therefore suffered a lack of attention towards the specific ways they enable knowledge about fashion.

In fact, these ephemeral materials are more than just promotional objects or, conversely, elaborate attempts to camouflage their commercial function. Rather, they may be understood as spaces in which fashion discourses are constructed and proliferate. These materials are not epistemic only in the manner they evidence information about the practices of the industry – from recording the backstage of the shows to marking the nature of collections – but because they perform the ephemeral nature of fashion, its practices and its ideals, and even its stereotypes. For example, Maison Martin Margiela includes the signatures of its team members in the s/s ’91 invitation, making a statement about the collaborative nature of its work, recognizing and using the role of the signature as index of authorship in fashion. Similarly, the graphic designer Paul Boudens uses his own blood, for Jurgi Persoons a/w ’98-’99 invitation, as a graphic tool to suggest the cruelty of the fashion industry, its inhuman working conditions and his own visceral approach to his work. Conversely, Van Beirendonck’s s/s ’90 invitation takes the form of a newspaper that elevates specific figures (e.g. photographers, make-up artists, graphic designers) of the Antwerp scene. Indeed, rather than an imitation of, or elevation to, an artistic practice, these practical devices become spaces where the tools and tropes of fashion are articulated and discussed in a form of self-reflexivity that, however, lacks uses and degrees of self-criticism like in the case of Raf Simons s/s ’03 press release. Claiming to be a critique of consumerism in fashion, the press release enacts a critical stance while hiding its commercial function and its participation in a consumerist sphere.

“Indeed, these ephemera carry in them an ambivalent knowledge to which their beholder must be alerted. ”

Indeed, these ephemera carry in them an ambivalent knowledge to which their beholder must be alerted. When speaking of autobiographies of designers, for example, the design historian Denise Whitehouse reminds us of the importance of building “critical strategies” to analyse the rhetoric of autobiographical discourse. In a similar manner, when discussing the epistemological scope of ephemeral promotional materials is not only important to discuss what they say but also how they say and what they do not say. In fact, the knowledge enabled by these materials is often standing in-between fiction and reality, which, at the same time, testifies to the nature of their epistemological value as well. In concrete terms, an invitation made out of a fabric sample, a press release written in the shape of a poem, or a blurred image of a garment contained in a catalogue can trigger sensorial knowledge about fashion. Indeed, such an object may possess a very peculiar manner of epistemic functioning that, once revealed, may reach a high degree of efficiency in delivering knowledge about fashion.

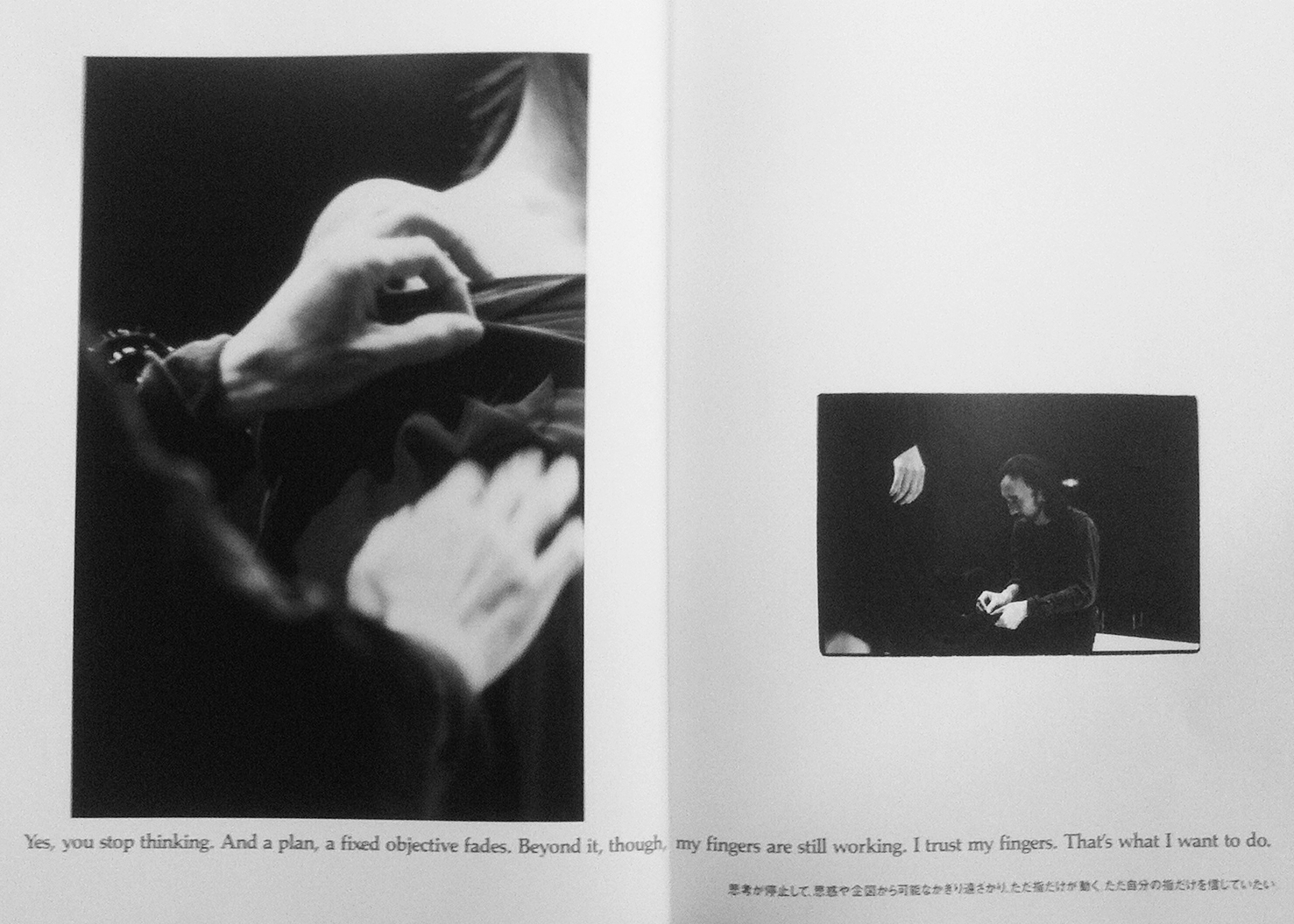

Thus, the questioning of these ephemera presupposes a quest for a fashion epistemology that, somehow, follows what the philosopher Hans-Jörg Rheinberger proposes as an “object-centered, materially-founded account of knowledge production.” [1] In his Epistemology of the Concrete (2010), Rheinberger urges the importance of thinking about “epistemic objects” as “things embodying concepts” in order to strengthen “the power of material objects—in contrast to ideas or concepts—as driving forces in the process of knowledge acquisition.” Rheinberger’s idea therefore explains why it is important to think of the way we know through these ephemeral materials in which fashion knowledge is not only transmitted through visual and textual language, contrary to what Barthes suggested in his The Fashion System (1967) about fashion magazines. Rather, in fashion ephemera, knowledge is also evoked through the material, testifying to the scope of material knowledge in fashion—a point embodied well by Yohji Yamamoto’s womenswear a/w ’91-’92 catalogue. “Yes, you stop thinking. And a plan, a fixed objective fades. Beyond it, though my fingers still working. I trust my fingers. That’s what I want to do”.

These words are written along two images depicting the designer’s hands working on a garment. By attributing a sort of corporeal independence to his fingers, the designer presents a moment of tactile sensibility, detached from conscious thinking: a carnal knowledge. Here Yamamoto suggests a distinction between rational and conscious thought on the one hand, and tactile perception through the fingers on the other. Somehow, this spread of Yamamoto’s catalogue enhances the properties of touch and tactile knowledge in fashion, stimulating a reflection on both the practice of creating garments and the transmission of knowledge within (and about) fashion. It seems to demand a point of touch rather than a point of view. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, to have a point of view means to have a “particular attitude or way of considering a matter.” If translated to the allusive point of touch, the idea of having an attitude, or a way of considering a matter, assumes further meanings, stressing how, in fashion, matters of touch correspond to matters of knowledge.

Notes

[1] Hans-Jörg Rheinberger, "A Reply to David Bloor: 'Toward a Sociology of Epistemic Things,'" Perspectives on Science 13.3 (2005): 406.