A Space for Self-Fashioning: The Countess of Castiglione’s Photographic Self-Image

The Countess of Castiglione, Virginia Oldoini (1837-1899), possessed a beauty that was renowned in 19th century European society, but which seems to have been all but forgotten today. Castiglione attempted to transform her reputation as“ Venus Incarnate” into a legend by commissioning over four hundred self-portraits by the photographer Pierre-Louis Pierson over a span of forty years from 1856 to 1895.[1] During the nineteenth century and even into the twentieth, photography was a privileged means of creating an image of status. Many aristocratic ladies, including Princess de Metternich, sought out the services of Pierson, but none placed herself in front of the camera as many times as, or in the manner of, Castiglione.[2] This article investigates how the photographs of the Countess of Castiglione—as both a form of subjectivity and self-objectification—served as a space of self-fashioning.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s catalogue La Divine Comtesse (2000) and Solomon-Godeau’s “The Legs of the Countess” (1986)—the two major surveys of the photographs of Castiglione— both acknowledge Castiglione’s agency in the production of her photographs. However, Solomon-Godeau argues that the Countess’ subjectivity is undermined by her reliance upon the modes of representing women in the nineteenth century.[3] While she alludes to common archetypes of femininity in her photographs, the photographs of the Countess are more than just a submission to pre-scripted definitions of womanhood. My work explores Castiglione as a creative subject in constructing various identities of femininity that both operate within and outside of standards of femininity.

Before exploring Castiglione’s subjectivity in the formation of her image, I want to clarify the definition of subjectivity being employed. Borrowing anthropologist Susan Kaiser’s definition of subjectivity, Castiglione experiences “both subjection (which implies being subjected to something-such as a subjection position-structured by others) and subjectivity (which implies having the agency to assert or articulate one’s own way of being and becoming).”[4] In other words, subjectivity in the formation of the self inevitably entails a process of subjection to a system or language structured by others. Though she subjected herself to a pre-existing language of femininity, the Countess alternatively exercised subjectivity in performing these tropes of femininity by adding her own creative touch. It was through the process of submitting herself to various forms of feminine identities that she was able to gain agency, while self-fashioning her person with “the pose, costume, props, and accessories” of her choice.[5]

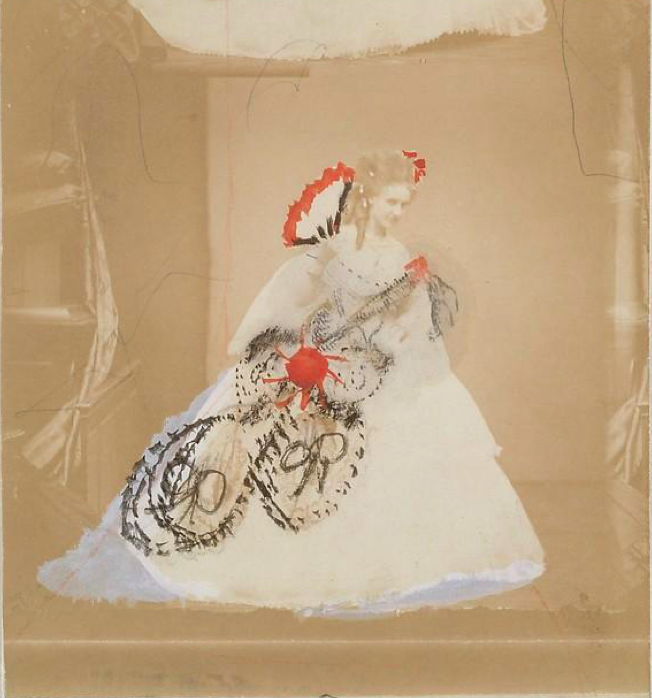

While the photographs of Castiglione should be accredited to their photographer Pierre-Louis Pierson, more thought should be given before claiming him as the artist of the photographs. As historian Pierre Apraxine notes, Pierson “is recorded as having said that Castiglione followed her own whim, and while he did not always comply, he admitted that it was she who always had the last word.”[6] Indeed, it may be more germane to refer to Pierson as an operator in executing the Countess’ directions. Among other instances, Castiglione’s agency in regulating her image is apparent in her handwritten remarks and painted sketches on prints of the photographs. The Countess’ pen marks and brushstrokes were part of a process of transforming the print into what could only be described as a “painted photograph.” Painted photographic portraiture consisted of the negative of the photographic print being transformed “into a hybrid product, half painting, half photograph, with the original photograph comparable to a painter’s preparatory sketch.” Though many of Pierre-Louis Pierson’s clients availed themselves of this practice, Castiglione took advantage of this practice “to an unprecedented degree.”[7]

“The painted photographic portraits of Castiglione elicit a fantastical setting and surreal beauty, complementing and exaggerating her contemporaries’ description of her as a goddess “descended from Olympus.””

Castiglione’s authorship of her image can be seen in these rough sketches of how she wanted her person to be painted and in her vivid description of the scene that was to unravel in the painting. Her colored brushstrokes that redesigned her costume or recolored her coiffure can be viewed along the lines of Foucault’s notion of “technologies of the self.” Foucault defines “technologies of the self” as “operations on their own bodies…to attain a certain state of happiness, purity, wisdom, perfection, or immorality.”[8] By refashioning her costume and changing the color of her hair for her final painted portrait—itself a form of disembodied self-fashioning—the Countess alters her photographed person to her liking. It was through her brushstrokes that Castiglione converted her photographed self in the print into a physical and literal “masterpiece.”[9]

The painted photographic portraits of Castiglione elicit a fantastical setting and surreal beauty, complementing and exaggerating her contemporaries’ description of her as a goddess “descended from Olympus.”[10] On the back of a print that would be changed into a painted portrait entitled Ritrosetta, the Countess wrote, “At a ball, a moonlit conservatory with flowers and water. A pale young man seems to be making remarks, which made the lady blush behind her fan. White crepe dress, lace stole, red camellia. Teased blond hair.”[11] Referring to herself as “the lady,” Castiglione as the author narrating the scene distances herself from her person in the print. With her painted sketches of a red fan, lace stole, and red camellias, the Countess turns herself into the likes of a heroine from a fairy tale or an object of her own fantasies. Through this act of self-objectification, she makes her person her art, resulting in her reduction of her person to an object on which she enacts her ideal self and fuels her imagination. Paradoxically, Castiglione’s subjectivity in the construction of her own image is gained only through her transforming her person to her masterpiece. By becoming the creative agent of her own image, she alienates herself from her person, as it becomes an object of her artistic ideals and an artwork of her designs. Thus, Castiglione becomes both the artist and the artwork through an act of self-fashioning, in which her person is used as a tool to facilitate her idealized, fantasized self.

Notes

[1] Pierre Apraxine, La Divine Comtesse: Photographs of the Countess de Castiglione (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 23, 11.

[2] Abigail, Solomon-Godeau, “The Legs of the Countess,” October 39.1 (Winter 1986), 67.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Susan Kaiser, Fashion and Cultural Studies (New York: Bloomsbury, 2012), 20.

[5] Solomon-Godeau, 7.

[6] Apraxine, 28.

[7] Ibid.

[8] L.H. Martin et. al (1988), Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault (London: Tavistock, 1988), 17.

[9] Apraxine, 23.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Apraxine 2000: 173.