Fashion, Photography, and the Mentally Ill Subject

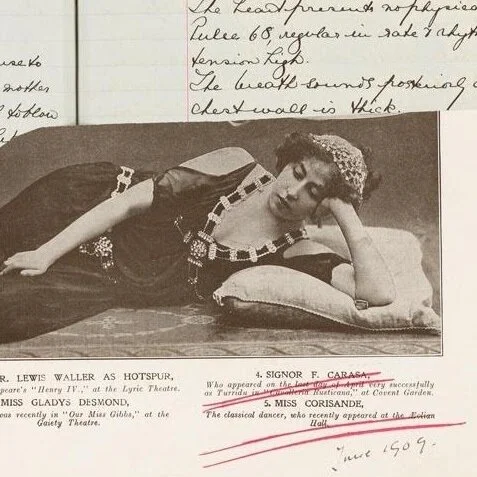

Figure 1. The records for Enid C., a patient admitted to the Holloway Sanatorium in 1906, feature a newspaper cutting taken after her discharge showing Enid under her stage name “Miss Corisande.” Holloway Sanatorium, Females No. 17 (Certified female patients admitted August 1905- March 1907), WMS 5160: 163–164. Wellcome Library, London. https://wellcomecollection.org/works/w3v6wrpt/items?canvas=144.

Part I

In the spring of 2021, trapped in my apartment and unable to travel to the archives, I received a welcome lifeline: The Wellcome Library announced its digitization of a series of century-old casebooks from Holloway Sanatorium, a defunct mental hospital in Surrey, England. Flipping through the images, I found myself transfixed by one page in particular: The individual scanning the book had laid a newspaper clipping from the collection across the text of one patient’s record, creating a new, multi-layered image (Figure 1). In the foreground is a woman, appearing under the stage name “Miss Corisande,” posed as a sensual odalisque. Behind her are handwritten notes, details from her previous stay at the Sanatorium and descriptions of her “impulses” to bring violence to herself and others.

This ad hoc collage mimics the moment over a hundred years ago when fashion photography as we now know it first took shape, when technology enabled the printing of image and text next to each other in turn-of-the-century fashion publications. [1] Here, image and text work together to expose interior space—of the hospital, of the mind, of the self. On its surface is a sensualized woman in fine dress; behind her lies the mental institution’s attempt to diagnose and treat her supposed insanity.

This is where I begin my exploration at the crossroads of psychiatry, photography, and fashion. Starting with the advent of psychiatric photography in the mid-nineteenth century, I focus on snapshots in which this constellation of visualization technologies appears through the twentieth century and into the present day. Throughout, I remain attentive to composition as well as content; what appears within the frame and, as in the case of Miss Corisande, the people and institutions beyond it.

“This preliminary research pairs psychiatric photography with fashion photography to show how internal states have been made external through the materiality of clothing and photography.”

I am currently writing a doctoral dissertation in the History of Science Department at Harvard that analyzes the use of objects, and clothing in particular, in the twentieth-century human sciences. There I argue that the materiality of things allowed a veneer of objectivity in practitioners’ study of subjectivity. Here, however, I want to explore a recurring theme from my project: the role of images in connecting interior and exterior states. Drawing on materials I have encountered in my research, this essay looks to the photography of Richard Avedon, Francesca Woodman, and Tara Wray to understand how clothing and photography are used to construct, understand, and treat the mentally ill subject—a feminized positionality that is both visible and invisible. This preliminary research pairs psychiatric photography with fashion photography to show how internal states have been made external through the materiality of clothing and photography. While the first two sections detail the work of more recognizable psychiatric and fashion photographers, respectively, the final two complicate these divisions by focusing on photographers who have lived with mental illness themselves, and who draw on the legacies of older images of mental patients and models alike.

Clothes and photographs are both “technologies of the self,” or material means to uncover the internal life of others. [2] This essay attends to how these different technologies interact. In this exchange, I argue, we can witness how these technologies were used to “fix” the mentally ill subject, in many meanings of the word—giving stable form to complex interior phenomena and producing specimens for others to study. The images were likewise intended to produce a cure or, at the very least, understanding. These efforts were complicated by the subject’s wielding of the same technologies, resisting objectification by speaking out in the “language of clothes” and by taking control of the camera. [3] Clothing and photography together provide a crucial lens to explore questions of objectivity and subjectivity, of disorder and normality, of gender and power.

Part II

In the 1850s, British psychiatrist Hugh Welch Diamond used the newly invented medium of photography to capture collodion images of his female patients at the Surrey County Asylum. Commenting on the project before the Royal Society in 1856, Diamond argued that the images could help the psychiatrist not only understand mental disorders but also effect a cure. One patient, Diamond noted, “could scarcely believe that her last portrait representing her as clothed and in her right mind, would even have been preceded by anything so fearful” as her preceding madness. Diamond emphasized that the unnamed woman “will never cease, with these faithful monitors in her hand, to express the most lively feelings of gratitude for a recovery so marked and unexpected.” The photographs captured and connected the patient’s exterior and interior states, with clothing serving as an important clue to the storms within—the photograph of the “cured” patient featured her “clothed and in her right mind.” In this context, clothing, and specifically a polished self-image, was integral to recovery, the photographs serving as “faithful monitors in her hand” indicating the depths from which she was saved. [4]

Fast-forward fifty years and Diamond’s practice of psychiatric photography was enshrined in the records of mental hospitals around England. Exemplary in that regard is the Holloway Sanatorium. The casebooks are replete with images, largely taken by the staff on hospital premises and pasted alongside text recounting patient activities and symptoms. A growing number of scholars have begun to attend to these pictures of patients. [5] I want to draw attention further to their form—images alongside identifying text—as akin to a fashion editorial. Making this comparison, I believe, illustrates how both styles of visualization (image and text) work to uncover and expose interior life.

Take the case of Lizzie G., who entered Holloway in May of 1889 and left “relieved” in the early months of 1892. Lizzie’s stay at the sanatorium was from the start expressed in the language of clothes. Her admission was accompanied by two certificates attesting to the case of insanity, which was “manifested chiefly by eccentricities” in her “dress, manner, intellect, [and] actions.” The first certificate mentioned she was “oddly dressed” and had “no stockings on.” The second stated that she “had destroyed nearly £4 worth of handkerchiefs [and] stockings in 10 weeks.” Upon admission, it was noted that she wore rubber slippers and “a thin cloak with a ribbon girdle around the waist.” The comments written during her institutionalization include mention of her refusing to wear boots and walking around in only her stockings, as well as her continued destruction of items of clothing “when she thinks they are worn and are soiled.” [6]

Figure 2. Detail from the casebook notes on Lizzie G. Holloway Sanatorium, Females no. 2 (Certified female patients admitted January-September 1889), WMS 5157: 177. Wellcome Library, London, https://wellcomecollection.org/works/yzm422u5/items?canvas=189.

This latter comment was written next to the only image of Lizzie (Figure 2). The photograph itself is difficult to read, both because it is faded and because of the expression on Lizzie’s face. We see Lizzie outside, wearing a simple dress with her hair pinned up. This is a different representation of Lizzie, one that does not focus on undress—her lower body is out of frame, preventing any glimpse of her notorious (un)stockinged legs. The pairing of text and image creates a dissonance as those markers of her insanity hinted at in the text are not present in the visual frame.

Fashion magazines blossomed during this same period as they embraced a more graphic form featuring both text and images. In his article on late nineteenth-century fashion journals, Christopher Breward characterized this new format by its “self-referentiality,” or “the deliberate use of illustrations to underpin, massage, and reflect the modern experience of the reader.” These illustrations built a fantasy world for women that helped ease them out of their separate sphere into “safe spaces of desire” in which to imagine freedom through consumption. This world was exemplified by the department store’s public consumerism. “The visual world of the department store, like the world of the magazine,” Breward wrote, “was one that did not necessarily rely on the rationality of the market system or predominant social and cultural ideals.” Indeed, the magazine layouts hoped to emulate the “admired disorder” of these stores. These images were irrational, almost otherworldly: a shared fantasy transformed into black and white on the printed page. [7]

“While asylum casebooks were not public documents, they shared features with the widely circulating fashion magazines of the period. Both sought to represent the current mood as well as an imagined, normal future.”

While asylum casebooks were not public documents, they shared features with the widely circulating fashion magazines of the period. Women such as Lizzie were captured at a particular moment in time, their journey back toward “sanity” recorded in unsparing detail. Likewise, fashion publications sought to represent both the current moment and an imagined, normal future. In both venues, combinations of images and text attempted to keep women (and, by extension, men) in their place while also illustrating something of their changing inner life. Quoting Breward once more, “[The] visual material chosen to display the latest fashions communicated subliminal messages which further enforced a traditional view.” [8] The images painted blatant public consumerism as fantasy; as irrational, perhaps, as refusing to wear boots and walking around in one’s stockings. But they also illustrated a growing desire to go and walk about, showing off new boots and stockings in the streets and in the aisles of bustling department stores. As such, both technologies helped visualize new, potentially destabilizing ways of being.

Part III

The publication of women’s magazines increased sharply after World War II, and photographs by Richard Avedon graced many of their pages. [9] Avedon became one of the twentieth century’s most famous portrait photographers and contributed numerous iconic images to the fashion press. His body of work also includes a lesser-known series of images taken in a Louisiana mental institution in February 1963. The photographs were captured during a trip through the South for a collaboration with James Baldwin, published in 1964 as a book titled Nothing Personal. Not much is known about what exactly led Avedon to the Jackson hospital; the photos taken there contrasted sharply with the other images included in the finished product. One biographer suggested that he used the hospital as a place to “hide” from the network of political boss Leander Perez. However, others have suggested that Avedon’s curiosity was related to his sister Louise’s diagnosis of schizophrenia, as well as her own institutionalization and suicide. [10]

Looking at Avedon’s work for two different but related projects—one on the “New Look” silhouette and another on dress in mental hospitals—I stumbled upon two photographs that seemed to belong side by side, even though they came from different continents and different decades. (Figure 3). Fashion writer Colin McDowell wrote that Avedon “treated his fashion shots as portraits, not just of a woman, but also…a dress and above all, an attitude.” [11] This section compares Avedon’s photographs to interrogate the role of photography in constructing and documenting an “attitude.” To do so, I use the concepts of focus and exposure—both as photographic principles and as reflections on the photographic subjects.

Figure 3. Two photographs by fashion and portrait photographer Richard Avedon. Left: Renée, The New Look of Dior, Place de la Concorde, Paris, August 1947. Right: Mental Institution #17, East Louisiana State Mental Hospital, Jackson, Louisiana, February 1963. Both images © The Richard Avedon Foundation.

The two pictures have similar compositions: a woman in a dress in the foreground faces away while figures in the background look toward the camera. These parallels make the differences between the photographs even more striking. One is outside, the subjects given a sense of movement in twirling dresses and long strides. The other is an interior shot, the women portrayed as sedentary, still. The skirt in motion imparts a sense of power to the faceless woman, allowing her to inhabit more space in the frame. Writing in the early twentieth century, psychologist and psychoanalyst J. C. Flügel noted that, “by adding to the apparent size of the body,” clothing “gives us an increased sense of power, a sense of extension of our bodily self—ultimately by enabling it to fill more space.” [12] This woman is thereby granted a larger-than-life self. She is the focus of the photograph, both in the sense of being its center and being portrayed in maximum resolution. All eyes go to her.

The woman in photographic focus in the Louisiana picture is not the woman facing away. That woman, who to my reading is the focal point of the image, is instead blurred around the edges, fading into the walls that surround her. I see this difference as not only a commentary on institutionalization but also as a meditation on the type of subject given normative agency. While the women in both photographs are faceless, one woman is given crisp boundaries by her public display and the other becomes part of an institution meant to return her to the outside world.

I want to briefly turn to another image from Avedon’s time at the hospital, a negative from the collections of the National Museum of American History (Figure 4). We see another figure in the foreground facing away from the camera, but here the concept of exposure is dominant. In photographic practice, exposure refers to the action of light upon the photographic medium. The brightest part of the image, represented in the negative by the darkest colors, is the straitjacket. This is contrasted with the bare skin visible through a tear in the man’s pants. Tightly bound by clothing, he is exposed by it—as a patient, as a man in need of help, as abnormal. Tightly bound in the space of the mental hospital, he is exposed by the camera’s lens.

Figure 4. Richard Avedon, Insane Asylum (B), negative, February 1963, PG.67.102.040N, National Museum of American History, Washington, D.C. https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_1334357.

The photograph from this negative was included in Avedon and Baldwin’s book. Baldwin’s essay is worth a close read. The project’s focus was the “American situation,” which Baldwin identified as the state of being “locked in the past.” With this came an accompanying “terror within,” one that “has something to do with that irreducible gap between the self one invents…and the undiscoverable self which always has the power to blow the provisional self to bits.” We are afraid, that is, of exposure: of ourselves or others poking holes in the self we have built. Our worst fear is that we may one day discover “that the self one has sewn together with such effort is all dirty rags, is unusable, is gone: and out of what raw material will one build a self again?” [13]

The same question could be asked of Lizzie, of the man lying down in tattered pants. As Baldwin’s metaphor suggests, the self is constructed not just within but also from the clothes on one’s back, the objects kept close at hand—a common idea in the realm of consumer psychology. [14] Out of what materials will one build a self? Fashion photography and advertisements provide one option. But such a framing shows how the readymade self of the department store has been ingrained as the norm, how visually we are trained to equate exposure with fear and irrationality. Comparing Avedon’s photographs in this manner, we see how photography participated in marking certain selves as desirable and eye-catching, and others as pitiful and difficult to face.

Part IV

Francesca Woodman was born in Denver, Colorado, in 1958. She died in New York City in 1981. In her short life, Woodman produced a trove of images that continue to be widely shown and discussed. Her signature style can be related simply, but her evocative photographs elude written description. Many of her famous images were taken in a spartan apartment in Providence, Rhode Island, that lacked a shower or kitchen. Rendered in black and white, the subjects, usually Woodman herself, were often nude or partially clothed and blurred as if caught in motion. I wish to look at Woodman’s work, colored by her suicide at twenty-two, not to retroactively diagnose but to demonstrate the shift in focus that comes when photographic subject and photographer are the same. Put simply, what happens when the person behind the camera is the one living with mental unrest? Neither psychiatric photographer nor fashion photographer (her dreams of becoming the latter unrealized), Woodman’s work gains meaning from its ability to create power in blurring boundaries—she is neither, but also both.

Figure 5. Francesca Woodman, “Untitled Photograph”, circa 1975-1978, gelatin silver print. Image from George Lange Collection. Courtesy George Lange © Estate of Francesca Woodman/Charles Woodman/Artist Rights Society (Ars), New York.

In 2019, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Denver staged an exhibition of Woodman’s work anchored around a box of photographs, letters, and ephemera Woodman had shared with classmate and friend George Lange. The leading image (Figure 5) was a portrait of Woodman amid tombstones, a camera obscuring her face. A review published in Vogue Italia as part of a column titled “This Is Not Fashion Photography” noted that, “This image taken in the cemetery is typical of her style because, having her face covered, she eliminates herself from the photo—but meanwhile, she occupies it more aggressively than usual: I am a camera.” [15] Lange described Woodman as “the fragile friend you could not refuse to help.” She had a “palpable” intensity, but “could also be a mess,” characteristics infused into her work. As Lange put it, “That mess is the texture of her work…somehow with her touch, that mess became poetry.” [16]

The words “mess” and “touch” are helpful to keep in mind when attending to Woodman’s dual role as photographer and subject. As the Vogue Italia review stated, Woodman is almost becoming the camera, blurring the lines between the machine and the person behind it. As others have noted, Woodman also employed reflective surfaces to do similar work, mirrors and sheets of glass “documenting the mechanics of the photographic medium” while simultaneously acting as “a lens through which we read the recognizable body features as strange or as a disfigured object, even as something detached from the body.” [17] That is to say, Woodman’s subjecthood was inextricably and viscerally tied to the photographic process, present in and around the bodies in her images.

That Woodman herself experienced depression gives deeper meaning to these photographs, which, like the images in the mental institution taken by Avedon, blur the boundaries of the subjects—mental health and photography, the women in the frame—both literally and figuratively. Even in the act of photographing, Woodman becomes an impossible subject to capture, at once human, animal, and machine. Since she controls the camera herself, however, any blur can be read differently than in the work of Avedon. Woodman does not want to be in focus. As she once quipped, “I am as tired as the rest of you of looking at me.” [18]

Figure 6. Francesca Woodman, From Space2, Providence, RI, 1975–78. Gelatin silver print. © Betty and George Woodman, the Estate of Francesca Woodman.

Exposure is an omnipresent theme in Woodman’s work, especially in her use of clothing and space. Woodman often hides parts of her body, paradoxically making it more present. Images such as those from her Space2 collection from 1976 (Figure 6) show a body in motion and in danger of moving beyond the very walls that attempt to contain it. Evoking “The Yellow Wallpaper,” an 1892 story by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, we see madness as transgressive, feminine, and both visible and invisible at once. Unlike Avedon’s photo of the woman in the mental hospital, here blurriness is reconfigured as power. With control of the camera, Woodman will not let you forget the power of the body, one that cannot be contained by the edges of a photograph or the walls of a room. This image was used to introduce a roundtable on Woodman’s work printed in Art Journal in 2003 where art historian George Baker commented, “If anything, she was documenting the limits of bodily experience, the impossibility of constituting the self.” [19] What I want to emphasize here is how this is treated not as something to be changed but as something integral to her experience of herself in the world, as a woman and an artist. This comes about, I argue, from her role as camera as well as subject.

“With control of the camera, Woodman will not let you forget the power of the body, one that cannot be contained by the edges of a photograph or the walls of a room.”

Part V

In 2018, photographer and filmmaker Tara Wray released a photobook titled Too Tired for Sunshine. The project was funded via Kickstarter, where Wray defined the phrase as “the experience of feeling so melancholy that not even a sunny day can raise your spirits.” The book features about eighty images taken between 2011 and 2018, a period during which Wray lived with depression. For Wray, the camera is a therapeutic tool: “Making photographs and sharing them allows me to get outside of my head and connect more fully with the world around me.” However, it is not reality that Wray seeks with her camera’s lens. Rather, as she explains, “I hope this work will inspire others to discover a sense of unreality in their own world.” In this section, I look at how in Wray’s work the camera-as-therapeutic lens shifts the subject’s body out of the frame and attempts to represent instead a “state of mind.” [20] Such a removal hinders any formulation of the (singular) mentally ill subject.

Wray’s work evokes a sort of whimsy, or an acknowledgement of absurdity and light even amid darkness. The book’s introduction, penned by writer Aimee Bender, notes that, while “Depression shades the world…voice remains voice, even muted, even struggling, and [Wray’s] visual voice cannot step away from playfulness…” [21] There are photographs of dogs, of coming storms, of animal carcasses. Collected in the book, these images are tied together by the state of mind of the person behind the camera, capturing the manifold experiences of mental illnesses that resist simple coherences.

Figure 7. Tara Wray, spread from Too Tired for Sunshine (Atlanta: Yoffy Press, 2018).

In one photograph, an adult and toddler stand next to a white fence (Figure 7). The adult’s face is obscured by a blue balloon; the toddler bends over, arms wrapped around a bright yellow balloon as if keeping it down to earth. The scene is domestic and familiar, a stereotypical suburban fence that could be anywhere. Without reading too much into this image, I want to draw attention to the differences between its two subjects. The adult has no face; it is lost behind a balloon that almost looks like the sky on a partly cloudy day. This motif of facelessness has recurred throughout the images I have analyzed here, which stand in contrast to the earliest images of psychiatric photography in England. There the individual’s face was scrutinized to form generalizations about mental illnesses. In the later photos, the reverse occurs, as the individual is made to stand in for something general. The child, meanwhile, holds a yellow balloon, a bright orb that looks like the sun itself. Perhaps childhood whimsy is lost in adulthood and depression—the sun replaced by the clouds, and the emotions effaced.

Based on the response to the photobook, Wray launched the Too Tired Project. The nonprofit aims to use “photography as a tool to help those struggling with depression, anxiety, and related mental health issues by offering a space for collective creative expression.” The Project runs an Instagram account, which archives submissions from artists around the world, and a publishing arm. [22] Expanding the project from solo-authored photobook to collaborative Instagram page has further emphasized the multiplicity of experiences of those with mental illness. It is tempting to look for themes in the images, and certainly some stand out. A black-and-white photograph from the “Winter Isolation” exhibition featuring a woman sitting on a bed staring out a window (Figure 8), for instance, instantly evokes Woodman’s work—the wallpaper of the room threatens to overcome the figure, who keeps her gaze fixed on the light outside—as well as that of Avedon, the woman’s face turned away from the camera’s lens. But what becomes clear from the grouping of these images is not these sorts of similarities; with the camera firmly in the hands of subjects living with mental illnesses, any idea of one generalized experience is decomposed into fragments, images of all types scrolling by on a screen.

Figure 8. Scott Offen, Grace at the Window, from “Winter Isolation,” Too Tired Project. https://tootiredproject.com/winter-isolation.

Part VI

A common way to describe both selfhood and gender is to say that they are performative. Joan Riviere, writing in the 1920s, argued that “womanliness” was a “masquerade,” a posturing to enact a non-threatening femininity and defuse the anxieties of a male audience. Judith Butler later built on this work in constructing her broader theoretical understanding of gender. Photography, too, is a form of performance; Teju Cole has called the camera “an instrument of transformation.” [23] The camera is, put simply, part of the performativity of fashion.

Many technologies of the self underpin its performance, and this essay has looked at just two—clothes and cameras— that together highlight the stakes of such a project. Curator and art historian Ann Marguerite Tartsinis wrote in her review of a 2018 exhibition of fashion photography that its collection “chart[ed] a liminal space between realism and fantasy pushing against the very definitions of each.” [24] The images I have selected for this essay likewise highlight this boundary between internal and external, reality and fantasy, self and other.

As the discussion of Wray’s work makes clear, the collection of photographs analyzed here is only a small fraction of a broader story. It is my hope that putting these images and artists together opens space to think more deeply about questions of representation, power, and selfhood at the intersection of fashion and mental health. The controversy surrounding the 2019 Gucci fashion week show in Milan—which featured a conveyor belt of models dressed in straitjackets and the powerful image of Ayesha Tan-Jones with “Mental health is not fashion” written on their hands— illustrates just how fraught this intersection can be. Tan-Jones took to social media after the show to explain the feelings motivating their protest, writing, “it is hurtful and insensitive for a major fashion house such as Gucci to use this imagery as a concept for a fleeting fashion moment.” [25] Further engagement with history, fashion studies, and psychiatry is needed to help us understand the roots of such anger and to help us fashion a different vision for our future.

Notes

1. “One Hundred Years of Fashion Photography,” Victoria and Albert Museum, accessed December 2, 2020. http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/o/one-hundred-years-of-fashion-photography/.

2. On the elaboration of “technologies of the self,” see Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault, ed. Luther H. Martin, Huck Gutman, and Patrick H. Hutton (Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1988).

3. Alison Lurie, The Language of Clothes (New York: Random House, 1981).

4. Hugh W. Diamond, “On the application of photography to the physiognomic and mental phenomena of insanity,” in The Face of Madness: Hugh W. Diamond and the Origin of Psychiatric Photography, ed. Sander L. Gilman (New York: Brunner/Mazel, 1976), 17–24. For a primer on Diamond’s project, see Sara Wetzler, “The Faces of Madness,” Psychiatric Times, January 14, 2021, https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/faces-madness.

5. On the use of photography at Holloway Sanatorium, see Katherine D. B. Rawling, “‘The Annexed Photos Were Taken Today’: Photographing Patients in the Late-Nineteenth-century Asylum,” Social History of Medicine 34, no. 1 (2019): 256–284; Katherine D. B. Rawling, “‘She sits all day in the attitude depicted in the photo’: photography and the psychiatric patient in the late nineteenth century,” Medical Humanities 43 (2017): 99–110; Susan Sidlauskas, “Inventing the Medical Portrait: Photography at the ‘Benevolent Asylum’ of Holloway, c. 1885-1889,” Medical Humanities 39 (2013): 29–37; and Susan Sidlauskas, “The Medical Portrait: Resisting the Shadow Archive,” nonsite 26 (2018), https://nonsite.org/the-medical-portrait/.

6. Notes for Elizabeth G., Wellcome Manuscript 5157, Holloway Sanatorium Case Book No. 2 Females: Certified female patients admitted January-September 1889, 173–178. https://wellcomecollection.org/works/yzm422u5/items?canvas=180.

7. Christopher Breward, “Femininity and Consumption: The Problem of the Late-Nineteenth Century Fashion Journal,” Journal of Design History 7, no. 2 (1994): 83–87; Ruxandra Looft, “Safe Spaces of Desire: Advertisements in the Nineteenth-Century Fashion Press of Berlin, Paris, and New York,” Fashion Studies Journal 4 (2017), https://www.fashionstudiesjournal.org/4-essays-/2017/7/28/safe-spaces-of-desire-advertisements-in-the-nineteenth-century-fashion-press-of-berlin-paris-and-new-york.

8. Breward, “Femininity and Consumption,” 77.

9. Ed Timke et al, “Comparing Major Women’s Magazine Circulation Across the 20th Century,” Circulating American Magazines, https://sites.lib.jmu.edu/circulating/2020/03/15/comparing-major-womens-magazine-circulation-across-the-20th-centuryby-ed-timke-and-wenyue-lucy-gu/. Accessed May 5, 2021.

10. Philip Gefter, What Becomes a Legend Most: A Biography of Richard Avedon (New York: HarperCollins, 2020), 263–265; Norma Stevens and Steven M. L. Aronson, Avedon: Something Personal (New York: Spiegel & Grau, 2017), 192–199. On Avedon’s sister and his work at the East Louisiana State Mental Hospital, see Jacob Pagano, “Nothing Real Can Be Threatened: Richard Avedon, Khalik Allah, and Communities of Portraiture,” Medium, September 18, 2018. https://medium.com/@jakepagano/giving-soul-richard-avedon-khalik-allah-and-the-touch-of-the-photograph-e4a0d79d0aae. Accessed September 18, 2020.

11. Colin McDowell, “Richard Avedon, Dior and How They Changed Fashion Forever,” Business of Fashion, October 29, 2016, https://www.businessoffashion.com/opinions/news-analysis/how-richard-avedon-changed-fashion-forever. Accessed May 5, 2021. For more on Avedon’s work in general, see the review of a 2009 exhibition of his work at the International Center of Photography: Cathy Horyn, “How Avedon Blurred His Own Image,” New York Times, May 13, 2009. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/14/fashion/14AVEDON.html. Accessed September 18, 2020.

12. J. C. Flügel, The Psychology of Clothes (London: The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis, 1930), 34.

13. Richard Avedon et al, Nothing Personal (New York: Atheneum, 1964). For more on the project, see Hilton Als, “Richard Avedon and James Baldwin’s Joint Examination of American Identity,” New Yorker, November 6, 2017, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/11/13/richard-avedon-and-james-baldwins-joint-examination-of-american-identity.

14. On the idea of this sort of “extended self,” and an overview of the studies focused on such an idea, see Russell W. Belk, “Possession and the Extended Self,” Journal of Consumer Research 15, no. 2 (1988): 139–168. This article remains, as of 2021, one of the most cited articles of that journal.

15. The original reads, “Questa immagine scattata nel cimitero è tipica del suo stile perché, avendo il viso coperto, lei si elimina dalla foto—ma nel frattempo la occupa con maggiore prepotenza del solito: io sono una macchina fotografica.” Translation by the author. Vince Aletti, “Questa non é una fotografia di moda,” Vogue Italia 829 (September 2019): 112. https://www.vogue.it/fotografia/article/questa-non-e-una-fotografia-di-moda-vogue-italia-settembre-2019. It should be noted, however, that Nora Burnett Abrams, the curator of the exhibit, argues that this picture is likely “more performance than a serious claim about her creative process.” Nora Burnett Abrams, “Portrait of a Reputation,” in Francesca Woodman: Portrait of a Reputation (New York: Rizzoli Electa, 2019), 105.

16. George Lange, introduction to Francesca Woodman: Portrait of a Reputation, 7.

17. Nora Burnett Abrams, Portrait of a Reputation, 100.

18. From an undated letter. Quoted in James McWilliams, “Ideas and a New Hat,” Paris Review, January 19, 2017, https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2017/01/19/ideas-and-a-new-hat/.

19. George Baker, Ann Daly, Nancy Davenport, Laura Larson, and Margaret Sundell, “Francesca Woodman Reconsidered,” Art Journal 62, no. 2 (2003): 65. DOI: 10.1080/00043249.2003.10792158. Emphasis added.

20. The Kickstarter page is available at https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1614253286/too-tired-for-sunshine-photographs-by-tara-wray. Accessed May 7, 2021.

21. Aimee Bender, introduction to Too Tired for Sunshine (Atlanta: Yoffy Press, 2018).

22. For more information on the organization, see https://tootiredproject.com. Accessed May 7, 2021.

23. Joan Riviere, “Womanliness as a Masquerade,” International Journal of Psycho-Analysis 10 (1929): 303–313; Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York: Routledge, 1990); Teju Cole, “Against Neutrality,” in Known and Strange Things (New York: Random House, 2016), 216.

24. Ann Marguerite Tartsinis, review of “Icons of Style: A Century of Fashion Photography, 1911–2011,” Fashion Theory 24, no. 2 (2020): 301.

25. The event and Tan-Jones’ protest were covered widely in the press. See Katie Mettler, “Gucci’s straitjackets draw a model’s silent protest on the runway: ‘Mental health is not fashion,’” Washington Post, September 23, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/2019/09/23/guccis-straitjacketsdraw-models-silent-protest-runway-mental-health-is-not-fashion/; Vanessa Friedman, “Before Sex, the Straitjacket?” New York Times, September 23, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/23/style/gucci-alessandro-michele-milan-fashion-week.html; Hannah Marriott, “Gucci model stages mental health protest at Milan fashion week,” Guardian, September 22, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2019/sep/22/gucci-model-mental-health-protest-milan-fashion-week.