On Mental Health, Lee Alexander McQueen, and Slow Fashion

Collage courtesy of the author.

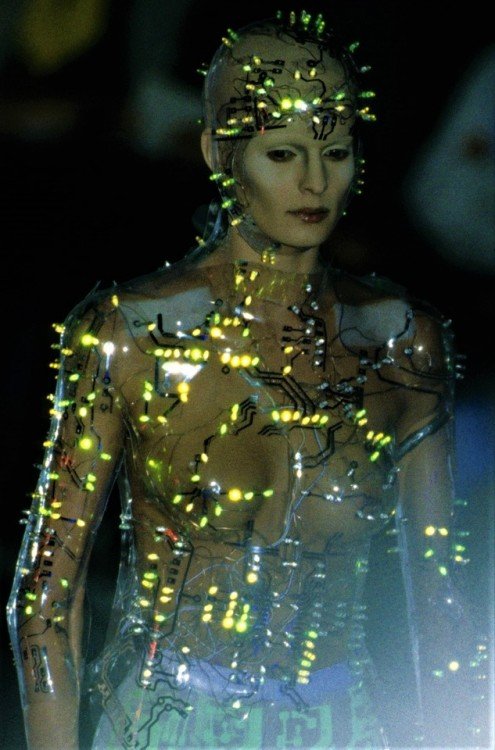

Why is it that when we think of mental health, we so often equate it with poor mental health? When exploring the relationship between mental health and fashion, inspired by FSJ’s call for contributions on the subject in early 2021, I thought of my own experience in the fashion industry, as the digital editor-in-chief of a prestigious publication at the age of eighteen, newly propelled onto (or rather, sitting by) the runways of London and Paris. I thought of how my own experiences with mental illness later turned me “out” of fashion: how I went from attending shows in the front row to a tranquil job in a different field, in a different city. Considering mental health in terms of fashion, for me, also evokes images of Alexander McQueen’s shows. I’m reminded of cages and how often they appeared in his work, echoing the poignant words of Antonin Artaud, “clous carrés cages.” [1] I thought of how often women – and men – were masked in his shows, defaced, wearing fashion as armor and weapon both; what McQueen would call a “psychological way of dressing”. Restriction, constriction, folly, VOSS’s “holding cell in a mental institution” (reminding me of the name of the latest Serge Lutens fragrance, La dompteuse encagée). [2]

Compelled to look back at every collection of his, I was reminded of the first McQueen look that moved me profoundly at the tender age of 13: a simple green dress worn by Kim Noorda – elegant, serene, uncomplicated. As I was saving countless images of significantly darker outfits, I was most awestruck by the ones in which beauty was the sole protagonist, in which technique could blossom freely, unencumbered by the additional (itself utterly wonderful) Sturm-und-Drang narrative: the gentle touch of a rose, the glimmer of a golden blazer, a soft Grecian silhouette. Instead of focusing on the darkness, the illness, the Gothic tales, could we not also see McQueen’s designs, and fashion by extension, as a tool towards good mental health? Why is it that the ephemeral, harried, and at times schizophrenic structure of fashion has come to obscure the solace it can give us?

Collage courtesy of the author.

Never quite an insider within the universe of fashion, I have often felt conflicted between my critical point of view, focused on content — on things that would remain indelible — and the fleeting, often superficial aspects of fashion many saw as riveting. Yet, fashion has often proved an ally rather than a foe in my journey: it used to be a great leveler for my mental health. Still, I wonder how growing up memorizing the names of countless models, each inevitably wearing a size XS, shaped my view of body image. I remember how money became an issue: to fully partake, to style myself in this street-style appropriate way, an effort was needed; suddenly, the utopian world of Fashion started to collide with more mundane truths. Questions arose: how do I manage the thrill of the extraordinary? How can I coexist peacefully with these few weeks of carnival in which all logic is turned inside out?

*

I turned eighteen four days after Alexander McQueen hung himself. At the time, I was devastated, as he was the designer I looked up to the most. Ironically, the first fashion week I would attend was the first without his show. As I moved to London, McQueen became a sort of shadow-figure, a Ghost of Fashion Past, accompanying me across town in bizarre coincidences and romanticized narratives. I wrote about it, trying to make sense of why his death affected me so much. A few months before McQueen had passed, in November 2009, Daul Kim had also died by suicide. Both events were like alarm bells, but I was too naïve, or perhaps too young to fully understand them. They were signaling that the systemic wholeness of this world I so idolized was in peril. Or perhaps rather, that it was no different than any other space, and that in it there was plenty of unrest, sadness, and madness, despite the picture-perfect images it generated.

In the mid-2000s, there was something gentle going on in fashion. It was an era of elegance rather than of extremes. Alexandre de Betak reigned supreme; his shows were a grand but mysterious affair, Dior Couture being their paragon with its exquisitely elaborate spectacles, full of something later Chanel mega-productions would lack: atmosphere. Before everything was available to anyone at home, we had to resort to poor-quality runway stills on Style.com. There was something almost sacred in the process. I would carefully copy the schedule of shows, New York, London, Milan, Paris, jumping from look to look, opening tab after tab, fighting against my then not-so-stable internet connection in order to download, classify, and later write. I would then moodboard these looks to create new associations: a very personal universe would emerge; a universe utterly distinct from business (from buying, even). Back then, bloggers were often utopic loners, sympathetic characters protected by their keyboards and friendships with fellow digitonauts. Before the rise of the narcissist blogger, prefiguring Instaculture, there was a haphazard culture of commenting and sharing.

There are two aspects of the early 2000s that really struck me today as potentially powerful forces in discussing mental health: still images and slowing down. It is worth noting the power of the images of the time: so tiny, ridiculous by today’s HD standards (mid-2000s stills are literally thumbnails), which would by themselves offer a narrative, later sharpened, or softened, by artful backstage shots such as Anne Deniau’s for McQueen. [3]

Image: Vogue

Take the aforementioned green dress. An encounter with an image: by a feat of our brain synapses, the dress becomes part of a mental (“digital”), very powerful wardrobe — wardrobe in the Warburgian sense of “Mnemosyne,” like an attic of the mind in which to store precious objects. There is something classical in such a process, substituting the possession of the time for its image: the art of memory. The Fall-Winter 2005 collection, of which the green dress is a part, was so classical. Classical is a word that is often despised in fashion, interpreted as old, dusty, boring. Yet it is everything but. Classical is what builds a capsule wardrobe, freeing the mind of hassle and clutter alike. Classical often turns into an heirloom, and escapes the trend-to-landfill circle, contributing to one’s moral balance. Classical is also often a synonym of silence.

It has been argued countless times that what contributed to Lee McQueen’s passing was the maddening, ever-increasing, capital-driven, substance-use-inducing accumulation of runways and collections (“the deadliness of doing,” to quote Michael Oakeshott). Creations were already memento mori by the time they were shown; fashion was so ruthless in its rota of constant production that it created a state of hyper-ephemerality, a negation of the ontology of the very things it produced. I believe that Alexander McQueen, amongst others, cared for the aura of objects, wished for his elegiac creations to transcend towards silence, towards a quieter place in which they could simply express and in turn empower their wearers. Without delving into the spiritual — perhaps animistic — implications here, I like to think that his parable, both personal and professional, points towards the need for Slow Fashion. Not only in terms of sustainability and ecological concerns (as important as these may be), which are talked about plenty: we should have time to decant clothes, to appreciate and treasure them. Perhaps McQueen’s second-last show, Plato’s Atlantis, is emblematic of where things got muddled. By accelerating the world of fashion, by live-streaming (at its core a laudable, democratic, and anti-elite premise), images were multiplied. Suddenly, we the spectators received information in the form of 3D videos, not 2D stills. We were a lot closer to TikTok’s rapid-fire content than the slow in-atelier shows of the past.

Image: Vogue

A decade later, we are ever-more surrounded by echoes and multiples, countless feeds repeating the same news, showing the same image, while this content is ruthlessly replaced at terrifying speed. As we are surrounded by this cacophony of media, of content, of what Andrew Sullivan calls “futility,” [4] I find stability in looking at the very images I was looking at back then, in the limbo of those quasi-internet-free-years, remembering the exact sensation of loading the next picture, the next dress. I long for that space in between one image loading and the next, fueling infinite possibilities for creativity and reverie — well-being.

Silence is fundamental to mental health, and I would argue birdsong, too — the quiet rhythm of beauty that surrounds us when we abandon our devices and reconnect with nature (so loved by McQueen). “In fact I try and transpose the beauty of a bird to a woman,” he said. [5] And I believe he managed to transpose not only the beauty but also the freedom of the bird, himself designing a way out of the cage, using his hands to craft artifacts that can protect our fragile — collective — psyche, gently shelter us against the imperatives of fashion and society alike.

Notes

[1] This line is difficult to translate: literally, it means “nails, squares, cages,” though the alliteration, the shortness of the words, the roughness of the initial k- sounds all reinforce the sense of imprisonment. Artaud himself notably spent years in what would then be called an “asylum.”

[2] For another perspective on the famous VOSS show, please revisit this article from FSJ: https://www.fashionstudiesjournal.org/longform/2020/5/17/alexander-mcqueen

[3] Hamish Bowles, host, “From URL to Front Row: Bloggers Dial-Up Fashion” In Vogue: The 2000s (podcast), November 2, 2021, https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/from-url-to-front-row-bloggers-dial-up-fashion/id1526206712?i=1000540487896

[4] Andrew Sullivan, “I Used to Be a Human Being,” New York, September 19, 2016, https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2016/09/andrew-sullivan-my-distraction-sickness-and-yours.html

[5] Ibid.