Covid Mom: A Year in Five Garments

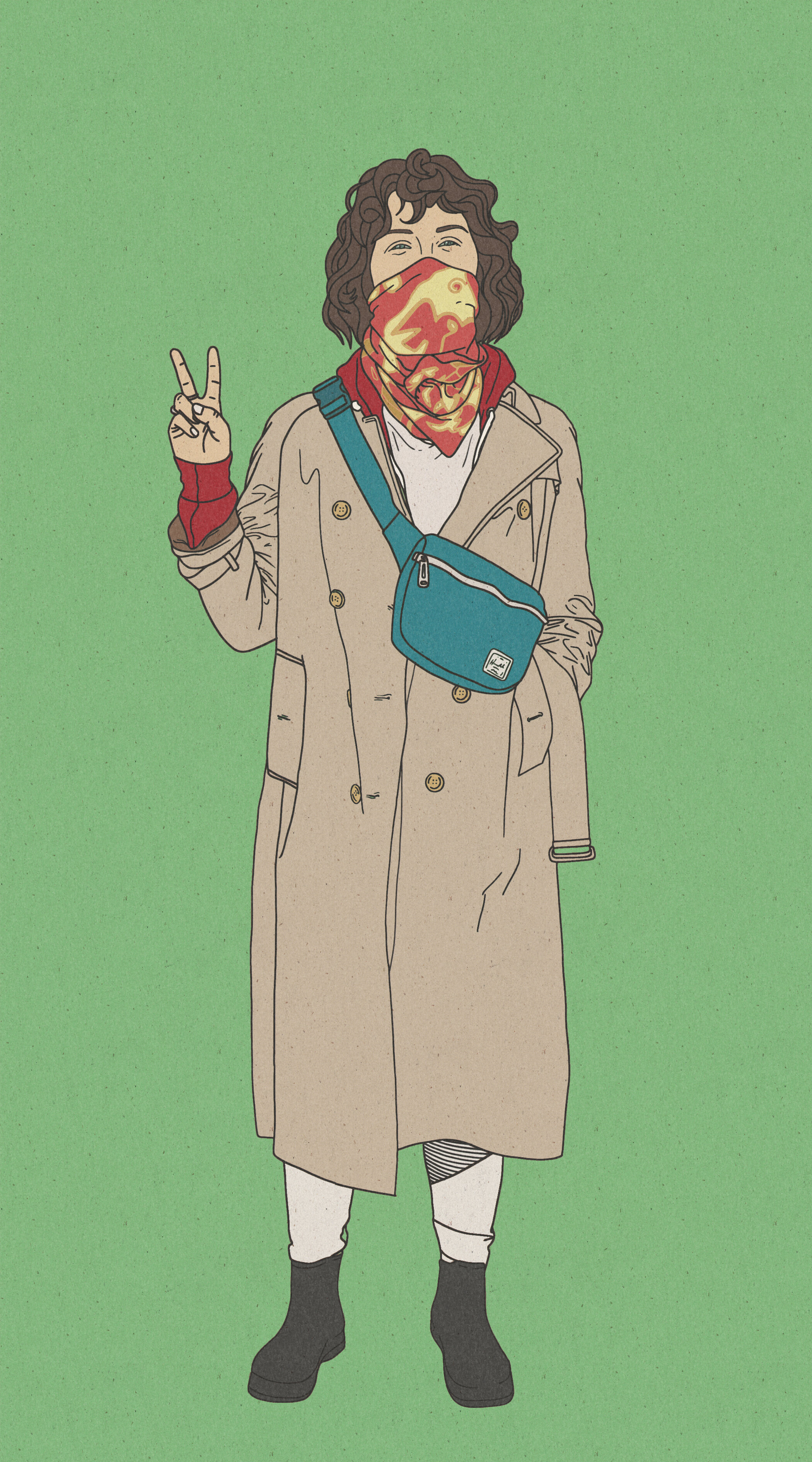

Image: Sultana Bambino

This is me in early April, 2020, from a photo by my son Theo, who was 6 then and has since turned 7. We were on one of our family walks around the block, which we would do once each afternoon and once each evening. School and daycare were both closed, so he and his younger brother were home, and my husband’s restaurant that had been set to open at the end of March was sitting empty as we waited to find out whether it would ever be able to open at all. I continued to work from home as I had already been doing for five years, only now I was crowded by two bored, needy children and another very stressed adult.

This was not a unique situation at all. All over the world, families were forced into this domestic pressure-cooker, and looking back on our clothing from the time tells a story of how that pressure exerted itself. When I look at this image now, I see my “Covid pants,” a distinction I gave to my nicest leggings when I imagined it could be possible to wear a single pair of pants for the length of the shutdown. I see my second-worst sweatshirt, low down in the rotation but still getting wear as the reality ground me down. And I see that silk scarf mask, the first face covering I experimented with before masks were universally recommended, before they became symbols of anything, before the supply chain kicked into gear and started pumping what they’d been making and selling in China for years into our markets; back when it still felt a little vulnerable and revealing to wear one.

In those first weeks, the public and private spheres were just beginning their great blurring that defined daily life in 2020. Where we once had work lives and home lives, work clothes and pyjamas, now we were just “in Covid.” As Rachel Cusk wrote in A Life’s Work, her memoir of motherhood, “In motherhood a woman exchanges her public significance for a range of private meanings;” [1] in Covid, we all have. Public significance is what a wardrobe of clothes is all about. When we were all stripped down to our private meanings, what was there to dress for?

“The contemporary expectations of motherhood have been centuries in the making. How fast can we tear them all down? ”

I came across a feature on working mothers from the New York Times from 1984, the year I was born, that begins (with veiled alarm) with a child identifying a sport coat as “Mommy’s dress.” [2] His mother, like her fellow 80s business ladies, like generations of domestic and care workers, like many of today’s “essential workers,” had a uniform to put on that made clear the boundary between her public self who could never be fully known to her family and her private self who existed mainly to care for them. For millions of us last year, that boundary collapsed, taking with it our motivation to dress for anything besides the desk-bed-kitchen circuit.

Let’s be honest: childbearing is sexist. For some reason, our culture has extended that to childrearing as well. And here we are, set back decades in our quest for equality, with more than 156,000 women’s jobs lost (disproportionately those held by women of color in education and hospitality) in the US in December, 2020 alone, while men gained 12,000 jobs in the same month. [3] We know how heavily care responsibilities—with children at home and elders at risk—have fallen on women this year. Are we doomed to the domestic once again, to a near-feudal relation between the sexes? The contemporary expectations of motherhood have been centuries in the making. How fast can we tear them all down?

Image: Sultana Bambino

I bought this dress in summer 2019, and it instantly became the kind of favorite that needs to be worn immediately out of the dryer. With two small children in our house, we do laundry pretty much every day, so this has gotten a lot of wear. It’s one of the harshest realizations of becoming a parent: fashion is really just future laundry.

“It’s one of the harshest realizations of becoming a parent: fashion is really just future laundry.”

What I appreciated so much about this dress this year was that it flattered what I think of as my Covid figure. Having experienced the body-size ups and downs of two pregnancies and too many years of nursing, I’ve adjusted to just being along for the ride with my body, but that doesn’t mean the ride doesn’t sometimes bring up some unflattering inner stuff.

It’s hard for anyone to look in the mirror and see change, whether that’s related to size, age, trauma, illness, etc. But I really firmly know that I can’t afford to model toxic self-criticism to my kids, who it devastates me to imagine thinking of themselves as anything less than beautiful and perfect in every way. Nor do I want to model anything that reinforces the messaging they’ll already get from this culture that bigger bodies are less valuable than smaller ones. The strategy 2020 has brought me is to split my inner monologue in two, where the second ‘me’ is actually nice to the other ‘me,’ genuinely valuing ‘me’ and showing ‘me’ the kind of love I hope to show other people in real life. Being kind to yourself? Groundbreaking, I know. But when I say things like “but you’re so cute like this! This dress looks better on you when you’re bigger!” in a soothing tone, I’m actually believing myself. Shout out to everyone on the front lines of the body-positivity and size-acceptance movements for creating and sharing the tools that make this kind of mindset shift possible for so many of us!

Image: Sultana Bambino

An overly generous friend called my hanging these masks off my fanny pack strap a “great mom hack.” It’s more just the only available option for keeping my own mask and both my kids’ masks on me at all times. They honestly look messy and stupid, but I’m not exactly in a position to care about that these days (or ever—who do I think I am?!).

So much of the transition from ‘person’ to ‘mom’ has, for me, been about that growing feeling that it’s ludicrous for me to try to look nice, because what I personally am is just a decaying sack of organs whose only function is to wipe two other people’s butts!

There’s a lot you don’t really hear about when you’re getting ready to welcome a child, but it’s not just what your body goes through (gross stuff, if you’re carrying it) or what you give up in your lifestyle (sleep, freedom, maybe some substances). There is woefully inadequate warning about the fact that becoming a parent means living with and integrating the fear that your child will die. People vaguely say that raising kids is “scary,” but it’s not just fear that you’ll make mistakes you can’t take back, or that you’ll have to confront your own wounds, both of which are very real and very hard, for sure. The “scary” part of parenting is the supercharging of that base fear we all already know—the fear of death—now externalized, because your own death isn’t the scariest one you can imagine anymore. This fear can be constant and pounding when they’re tiny and helpless, and I gather it winds right back up when they’re testing their independence. But it doesn’t go away in between, and learning to live with and not be decimated by it becomes a big part of the work. My point is: somebody needs to talk about fear of death in the baby books!

“The effects of the pandemic will continue to reveal themselves for years, but can we please discuss them more deeply than by asking whether sweatpants for work are here to stay? ”

This last year has brought collective fear and anxiety to heartbreaking levels, with grief and loss crashing in waves upon so many families. Even anyone watching from a relatively safe perch can see the further storms on the horizon, particularly the gathering clouds of the climate catastrophe that any sane parent sees threatening their children even more than themselves. Will the pandemic have taught us anything about how to collectivize the fight for the survival of our species? Parents are not the only ones with a stake in the future. As Adrienne Rich wrote in 1996, “this is surely one of the lines on which [Indigenous North American] and Black women have had a very different understanding rooted in their respective community history and values: the shared concern of many members of a group for all its young.” [4]

Changing the way we consume fashion is going to be a huge part of how we address this collective threat. We all know the horrors wrought by the fast fashion industry, even as they remain abstract to the fortunate among us: not just the human costs of cheap, brutal labor, but the emissions, water pollution, textile waste in landfills, and microplastics. We know we can’t continue like this, and we are all invested in clean air and water, whether or not the faces in our nightmares belong to children of our own. The effects of the pandemic will continue to reveal themselves for years, but can we please discuss them more deeply than by asking whether sweatpants for work are here to stay?

The pandemic and world war that raged a hundred years ago saw governments ask designers to use less fabric and avoid needless decoration: “Make economy fashionable lest it become obligatory,” pleaded and/or threatened one slogan. [5] For better or for worse, our governments aren’t getting involved this time; the job of pressuring the industry to ration, to reuse, to upcycle, and to innovate now falls to the culture. So how do we resist the excesses of another Roaring 20s? Have we learned enough to look to Black and Indigenous wisdom to lead us, instead of merely stealing the signifiers of their traditions, resilience, and creativity?

This is what I think about when I look at these dumb little masks dangling off this dumb little bag.

Image: Sultana Bambino

Okay fine, you got me, I’m from Canada. [6] A lot of people here love winter, though I am not one of them. As a transplant to Quebec, I am especially lost in a culture whose adopted anthem is a song called “Mon pays c’est l’hiver” (“My country is winter”). The Quebecois love their winter carnival, their outdoor hockey rinks in every neighborhood park, this jolly snowman mascot, urban cross-country skiing, drinking hot booze out of a hollowed-out cane, etc. All of it is genuinely amazing; I’ve just never been able to participate for more than a few minutes without becoming completely miserable and needing to go inside. It’s cold out, people!

I’ve been shocked to witness how many Quebecois parents join in with their kids playing in the snow. I traditionally prefer to stand around as my toes and nose go numb, the latter with a permanent drop of snot dingle-dangling off the end. Observing this, I soon realized that these parents’ trick was not just being of hearty Quebecois stock, impervious to the cold and/or drunk off cane booze (who’s to say?): the trick was that they were dressed just like their children. These adults wore Gore-Tex mittens, hats with ear flaps, and, most notably, adult snow pants.

Having previously been a cliché of a Brooklyn mom with my clogs and tote bags, I found the snowpants to be a bridge too far. Any parent willing to put them on gets my respect for prioritizing being active outdoors with their children year-round over the fear of being judged by a self-conscious idiot (me), but I couldn’t get over my vanity.

Except that now we’ve entered the Covid winter we’ve all been dreading since last spring. And kids can’t have friends over or do any of the indoor activities the city usually offers. So, as temperatures started to drop in November and safe park hangs got shorter, I realized I needed to bite the bullet and admit where I really am, both in geography and stage of life. I live in a cold-ass climate, I’m a damn mom, and this pandemic isn’t going away. I needed a one-piece.

I found this gal on ebay. She’s technically a “snowmobile suit,” and she’s straight out of the 70s. She’s navy with a sheen, stirrups, a leather belt with a brass buckle, and a faux-fur collar. Big pockets right there in the front, presumably for cigarettes, judging from the faint odor that clung to her out of the box. Smoking on a snowmobile? Now there’s the picture of a winter activity I can connect with. I’ve never named a garment before, but this is Claudine.

So now I watch my kids throw themselves in the snow with abandon while I drink hot liquids from a Thermos (still working my way up to the cane). Sometimes I even join in a snowball fight, relishing the catharsis of painlessly pelting my tiny tormentors. There is some measure of reconciliation between my self-concept as a stylish young city gal and the reality of my life as Covid Mom: The Winter Soldier. Reader, I hope you find your Claudine!

Image: Sultana Bambino

I may not get out much, but I’m aware that home tie-dye has been a widespread Covid trend. It feels so important to eke out little spaces of creativity and productivity. It’s also an inevitable craft to do with kids when you’ve already built a popsicle house, made potato stamps, and run out of pipe cleaners but you can’t bear to let them watch another five hours of TV.

Theo was super engaged with this indigo dye kit I bought—for about 20 minutes. Then he got bored and I had to finish dyeing all the stuff we’d prepped while he watched Pokemon and ignored me. It’s a cliché to say that we learn more from our kids than they learn from us, but this was a great example: I thought I could teach my son to patiently, methodically craft something he could take pride in, but he ended up teaching me, once again, to only start activities if I want to do the whole thing completely alone and then also clean up after myself.

Learning lessons from kids is not exclusive to moms, nor even to parents. There are so many ways that communities nurture intergenerational bonds, and I want this collection of stories about motherhood to be just the beginning of exploring all the ways people “mother.” There are so many examples around us that prove how expansive the category is; a colleague pointed the other day to brand-new US Vice-President Kamala Harris as an example of how dynamic the label could be. Harris is a step-mother, has helped raise and nurture multiple young people in her family, and as a woman in political power she cannot escape the system of symbols that will mother-ize her in the minds of Americans.

“There are so many ways that communities nurture intergenerational bonds, and I want this collection of stories about motherhood to be just the beginning of exploring all the ways people “mother.” ”

We see you, step-mothers, adopted mothers, queer parents, almost-mothers, grieving mothers. So many of you shine brightly in my own life, but you are regrettably not represented in this collection. Motherhood is so much more than reproduction, pregnancy, and birth, and I hope that future collections on this subject can expand to celebrate more non-traditional ways of making families. In the same way, I hope this collection reaches readers around the world who might like to share their experience with us in the future. I’ve had so much fun putting this issue together and I’d honestly like to do this forever, so if you know someone who might like to write or be interviewed about fashion and motherhood, and whose cultural experience is not represented here, please help me find them!

This sweatshirt, though it doesn’t pulse with the memory of mother-son bonding I was trying to create, does now speak to me of a certain dogged persistence. I finished the thing, didn’t I? I kept parenting, even if my kid didn’t notice. And even though I was mostly dyeing t-shirts for him and his brother, I managed to make this one thing for myself. When I look at this sweatshirt in the future and am reminded of my Covid-era parenting, I have to hope that’s what I’ll see.

Illustrations by Sultana Bambino

Notes

[1] Rachel Cusk, A Life’s Work, 2001, p. 3

[2] Anita Shreve, “The Working Mother as Role Model,” New York Times, Sept 9, 1984

[3] Diane Coyle, “Working Women of Color were Making Progress. Then the Coronavirus Hit.” New York Times, Jan 14, 2021.

[4] Adrienne Rich, Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution, 1996, p. xxiv

[5] Luz Claudio, “Waste Couture: Environmental Impact of the Clothing Industry,” Environmental Health Perspectives, Vol. 115, No. 9, Sept 2007, https://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/doi/full/10.1289/ehp.115-a449

[6] I’m from the parts of what we call “Canada” that are the traditional territories of the Anishinaabeg, the Mississaugas of the Credit, the Haudenosaunee, the Wendat, the Chippewa, and the Kanien’kehá:ka. From my understanding, we should be calling these places “Tkaronto” and “Tiahtiá:ke,” but I know them as “Toronto” and “Montreal,” and I’m still learning.