Super Sharp: Fashion Space Gallery

Fashion Space Gallery (London), February 1 - April 21, 2018

Super Sharp is the first iteration of RTRN Jungle II: a series of events and exhibitions presented by Tory Turk and Saul Milton at London College of Fashion’s Fashion Space Gallery (1 February- 21 April). Here, the duo come together as an independent gallery curator (Turk) and a member of Chase & Status (Milton). The exhibition’s title, Super Sharp, draws reference from the 1996 DJ Zinc track Super Sharp Shooter, and is an ode to the flaunting affluence present in the UK subculture scene of the nineties.

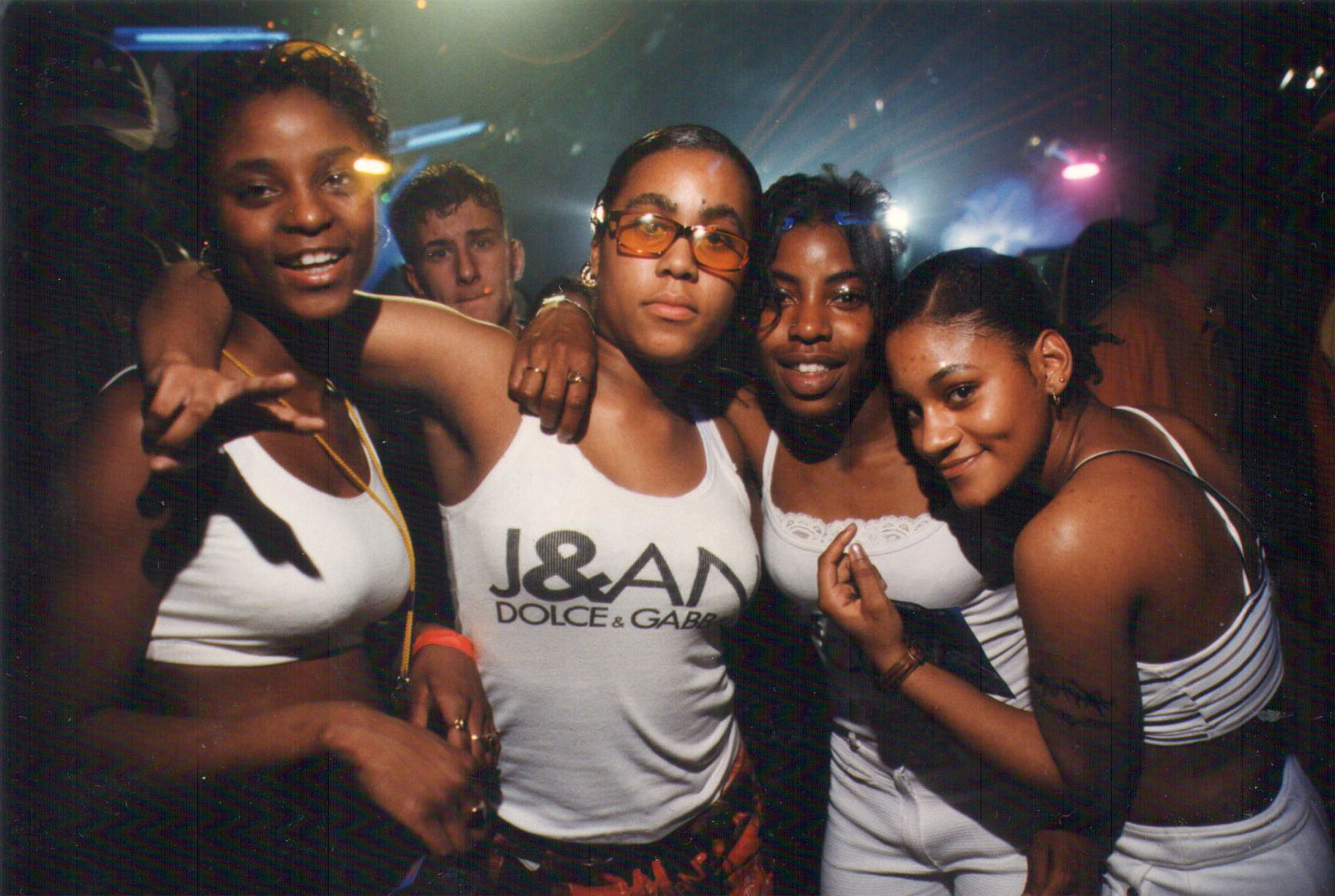

The series forms a nostalgic documentation of the styles which became iconic during the nineties rave scene. During this time, clubbing culture truly obtained its identity: It was a time during which dress codes and entry to club venues became stricter, and the term “peacocking” fell into the lexicon of club-goers. This new raving style, comprising of an eclectic mix of Jungle and UK Garage, became synonymous with a style of dress more commonly associated with the luxury Italian fashion scene. Labels including Versace, Moschino, Iceberg, and D&G became explosively popular on the dance floor of some of the most iconic UK club venues. The popularity of electronic dance music mixed with relaxed reggae beats and American hip hop prefaced club-goers’ appropriation of American hip hop styles more commonly associated with black culture in 1980’s New York.

A newly emergent (or perhaps resurgent) interest for this style of dress in the present is what prompted the duo to come together to present the musical scene associated with the sense of rebellion at the time. The two curators initially came together in 2014 when Turk curated an exhibition called A Streetstyle Journey involving key influencers in the styling process. One of these influencers was Saul Milton, who told Turk about his extensive collection of Moschino garments, and how he would really like the opportunity to present an exhibition which explored Jungle Style further. Milton’s original collection included over 1000 pieces, which Turk described as a “treasure trove for a curator.” The brash, printed two piece suits and logo-clad garments are a testimony to the fast-paced, breakbeat style of electronic dance music. Despite the relaxed and carefree nature of ravers, it somehow felt right to fuse together the effortlessness of urban combat gear with flashy designer labels.

What seems most interesting about the exhibition concept is the mixing of high and low design styles, with luxury Italian labels such as Moschino and Versace worn by young people in clubs; acting as a sort of uniform to aid their desire for posing to be seen. Inside the exhibition, despite the smallness of the space, a few select garments from Milton’s collection are of central focus. Situated alongside a selection of original analogue photographs taken in clubs in the nineties, as well other printed memorabilia, the small gallery is really brought to life by a flow of quotations from key music influencers printed onto the walls.

Narrated by printed quotes from a combination of journalists, DJs, music enthusiasts and photographers from the time, a passion for the UK Garage scene pervades the room and acts a deeply personal yet accessible documentation of nineties rave culture. Journalist Bethan Cole states: ‘‘Getting ready for a Garage night could take all day!’’ indicating the extent to which these club nights were important to the youth of the time. There is a section of the exhibition called ‘Bravado’ which contextualizes the visually striking garments on display. This section includes around 50 photographs by Tristain O’Neill, taken in the mid 90s, which document individuals engaging in the uplifting spirit of the scene—dressing to be seen and dancing to be remembered. These club photos capture how fashion and style collided in the raves to create the “Jungalist” identity and the form of dress which prompted the need for stricter door policies and a more restricted attitude towards clubbing.

Visitors are also given the opportunity to listen to Jungle sounds through headphones positioned at certain points in the exhibition space. Although a very simple technique, I felt this was a particularly poignant addition to the space that allowed people to both view and listen to the sounds and styles being explored. For an exhibition documenting both fashion and music, it is surely paramount to its execution to include a multi-sensory experience.

Upon further reflection, however, I realized that the space could have been heightened in terms of its immersive offering, allowing viewers to truly lose themselves in the space and experience the feeling of being present at a UK Garage night. This could have been achieved by the addition of a virtual reality offering, or even a separate room curated to replicate the overall sensory experience of a clubbing environment. Particularly for viewers unfamiliar with the subject being explored, additional elements of lighting, multi-layered sounds and even temperature changes could have offered a greater physical embodiment of the topic. Especially owing to the exhibition’s motive of ironing out the blurred and often misrepresented nature of the scene on the internet, a physically challenging and engaging presentation could have really lifted the communication of the subject matter. Milton noted how the time felt right to present the styles of this era because, ‘’The kids today look back at the 90s and want to experience ‘it’ themselves.’’ As a viewer expressly interested in the potential to push fashion curating through multi-sensory installations, I felt the curators could have taken more risks. Although the Super Sharp installation is overall very effective, the exhibition leaves ample space to further experience the core of the subject: something which will likely be achieved as RTRN II JUNGLE continues with DJ tours, documentaries and music.

Prior to visiting the exhibition, I was apprehensive that the space would be represented as a personal collection, and something which only resonated with the curators in a nostalgic sense. However, its situatedness at the London College of Fashion meant there was an awareness of the need for the exhibition to be accessible and aimed at a wide and varied audience. The effect of the artifacts on offer, given the small space, was not too much and not too little as the balance of clothes, headphones, text and printed matter was enough to create a narrative flow. Despite the potential for a more immersive offering, Super Sharp’s intention of being an entry point for a wider exhibition series is definitely an effective teaser and a space which leaves room for further intrigue into the world of nineties music culture.