L’Orient Exotique: Couture, Culture, and the Colonial Dreamscape

A few years back, designer Sabyasachi Mukherjee hired me as a model for a Diwali preview show in his Kolkata store. I was a relative newcomer in the industry then, but Sabyasachi had remembered my name, and it was a big deal for me. When I got there, his team was busy with last minute preparations to make the evening memorable for their very selective list of invitees, and the store was decked out with added elements to lend it a festive look. There was a separate kitchen area adjacent to the café in his store and every entrant would be asked very politely for their choice of tea or coffee. After having a cup of tea and changing into my costume for the evening, I made my way through the guests and found Sabyasachi so I could ask him what I should be doing that evening. I had to, because there were no signs of a photoshoot or a catwalk about to happen, and I was thoroughly confused. Perhaps amused by my confusion, he smiled and whispered to me that I should not spend the evening thinking of myself as a “human mannequin.” Instead he suggested that I take any corner of the store to do whatever I pleased and enjoy the rest of the evening.

I therefore sat in a corner of the main area in the store and read through a copy of Reader’s Digest. I remember being very surprised and thinking to myself that it was the easiest assignment I had ever done. I did not think of myself as the model hired for the evening to strut up and down a ramp, but rather like one of the customers in his store, wearing a Sabyasachi piece that I could never afford. Thinking back, I now realize that no matter what I did that evening, I was still the model showcasing his creations, performing a kind of aesthetic labor made to look effortless and authentic. Apart from the usual act of sporting the designer’s creation, my labor for the evening was extracted through my physical presence and my time devoted. He had skillfully and effortlessly recast the type of labor traditionally expected of or required from a model, and like everyone else, I had happily bought into it.

This is the crux of Sabyasachi’s marketing strategy. He sells aura over object, [1] lifestyle over product. He de-emphasizes the commerce of his business to a point where it is not even visible anymore. But conversely, the images used to advertise the products create a perceived sense of cultural authenticity that invites the consumer to buy into a pseudohistorical cultural discourse that I call Sabyasachi’s “Colonial Dreamscape.”

Even though Indian fashion is multifaceted, there are two main sectors: the prêt lines, which are ready-to-wear clothes sold in chain clothing stores for the general consumer and are predominantly western or western-influenced along with a select few “ethnic wear” brands like Global Desi, and the other is the bridal wear, which is more niche and custom, and almost a separate industry within Indian fashion. The designers of bridal wear are the biggest players in Indian fashion, for example, Sabyasachi Mukherjee, Tarun Tahiliani, the designer duo Abu Jani and Sandeep Khosla, Raghavendra Rathore, and Anita Dongre (who also owns the prêt brand Global Desi). As the price of their products are generally out of reach to the middle-class consumer, these designers mainly cater to celebrities and ultra-wealthy elites. Yet, like most couture brands, image-driven marketing and editorial campaigns are far-reaching and influence industry standards.

Recent contemporary bridal wear campaigns borrow heavily from the types and traditions of photography in India during colonial times. The fashion images produced by Sabyasachi Mukherjee and his brand for a recent bridal wear collection are a prime example of this emerging trend. Not only is Sabyasachi one of the most successful Indian designers with an overt restorative cultural agenda, he is also a trendsetter in the couture bridal wear industry and what he does is often emulated by the rest of the industry. Through an analysis of his work, contextualized in an historical framework, I argue that the nostalgic revivalist-nationalist ethos that Sabyasachi so emphatically adopts in marketing his work consigns a value to his pieces that goes far beyond their monetary value. His pieces become a part of a postcolonial conversation about tradition, culture, and identity, and thus become symbols of a value system that cannot be correctly represented through currency.

Indian Photography During the Colonial Period

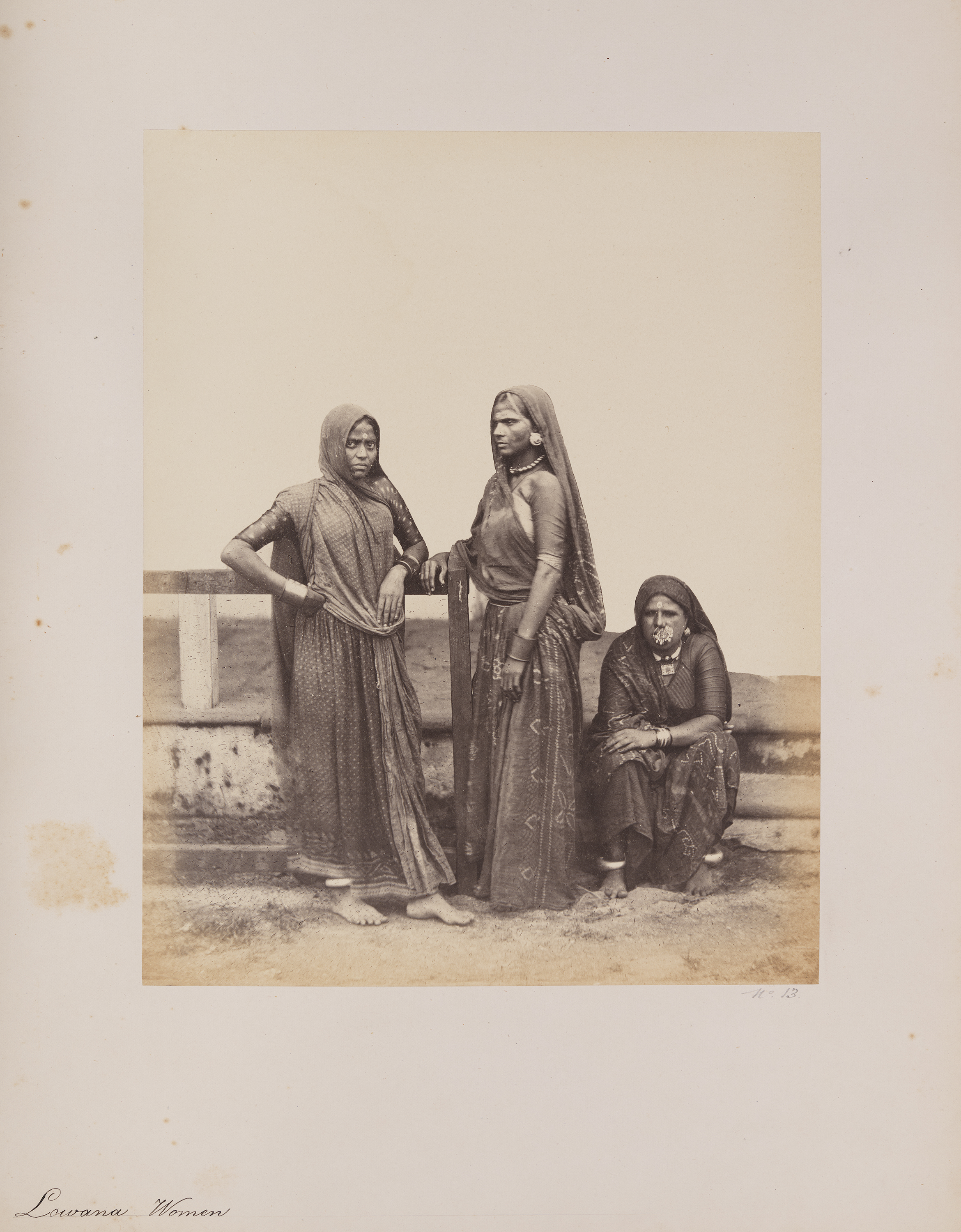

Photography came into the Indian subcontinent by the mid-nineteenth century during colonial rule, almost concurrently with its appearance in the West. By the 1850s, British photographers started to use the new apparatus in different regions of India to capture local realities. [2] These included the governed land and its architecture, as well as the subjects of colonialism. Unsurprisingly, these amateur ethnographic efforts enjoyed the endorsement of the colonial government. It fulfilled the government’s need to document the colonized land and produce a body of visual knowledge to better understand the subjects. In fact, photography quickly became one of the key tools in ethnographic and ethno-inflected efforts in the country. While British rulers—in equal measures confounded and fascinated by the culture of the new land—collected jewels, stones, artifacts, etc., photographs allowed them to capture likenesses of whatever subject or object they could not keep in a similar fashion: It enabled the colonial rulers to collect the non-collectibles. [3]

A shift towards photographing native inhabitants during this time gave birth to a new genre called “racial types.” In 1861, the Government of India issued a notice to local governments to collect photographs of “races and classes within its borders” along with brief accompanying notes. [4] The eight-volume collection titled People of India (edited by J. Forbes Watson and Sir John William Kaye) comprises photographs of a wide breadth of native Indians. Between 1860 and 1880, other notable volumes like Oriental Races and Tribes: Residents and Visitors of Bombay (William Johnson), and The Costumes and People of India (by W. W. Hooper and Surgean G. Western) were also published.

As photography grew more popular, it even became standard practice for native royals to employ photographers in their courts. Native photographers took up this opportunity with great keenness, becoming “increasingly focused on Indigenous representations of culture and power.” [5] As a result, we see a large number of photographs of native princes, kings, and daily proceedings of their courts without the presence of representatives of the colonial rulers. [6] In fact, the absence of the colonial overlords became one of the defining features of these royal photographs.

Although mimicking key colonial aesthetic forms, [7] Indian photographers deviated from the Western ethos and practices of photography in interesting ways. While in the west the camera was hailed as an objective recorder of events and realities, Indian photographers used the camera to “make a purified, eternal statement.” [8] As Gutman observes, traditional Indian paintings strive towards the depiction of the ideal, depictions not to be considered as a moment in time, but timeless. In Indian paintings, Gutman quotes Coomaraswamy, the portrayal is that of a “continuous condition,” [9] melding together past, present, and future. This aesthetic was carried forward in Indian photographic portraits. Royal photographs therefore arguably strive not just to freeze a moment in time, but to encapsulate the timeless essence of valor and power, or glamour and beauty. Indian photographers took up the new medium and imbued it with distinctly Indigenous standards of artistic expression.

“While in the west the camera was hailed as an objective recorder of events and realities, Indian photographers used the camera to “make a purified, eternal statement.””

Raja Deen Dayal was one of the eminent photographers of the era and was appointed the court photographer to the Nizam of Hyderabad. In 1896, he opened the largest photo studio in Bombay, and found patrons in both wealthy Indians as well as British officials. [10] Along with the studio in Bombay, he also had studios in Hyderabad, Indore, and Secunderabad. In his Hyderabad zenana studio, he photographed Indian women in purdah—a form of social segregation in Hindu Indian households where women were supposed to restrict themselves within a certain section of the household and not appear in front of unknown men. [11] As opposed to the racial type photos that focused mostly on the uneducated and rural natives of the land, his clientele was almost exclusively made of women of elite households. This collection serves as one of the earliest turn-of-the-century examples of portrait photography of elite Indian women.

Since women were subject to purdah, photographs of Indian royals remained predominantly male-centric for a very long time. It was not till the late nineteenth and twentieth century that photographs of women, especially women belonging to the elite households of India, became acceptable and commonplace. Photographs of royal women, therefore, serve a dual purpose: on one hand, they have become the quintessential representations of glamour and beauty, of royal Indian sophistication and coveted lifestyle, and on the other they serve as a record of the movement from the interiors to out in the world; the shifts in the role of women and their increasing influence in social spheres; from obscurity and silence to political power and social reforms.

These photographic archives—of royal Indian women and earlier photographs of everyday women found in the racial type genre—while not the mainstay of quotidian contemporary urban-cosmopolitan Indian visual culture, do tacitly remain in the background to remind us of different sides of our colonial past, albeit sometimes a highly selective, exclusive history. Contemporary fashion images produced for the bridal wear industry play a very important role in keeping this archive alive, by constantly referencing and recreating them. These archives also inform us about how the photographic practices of the past inflect the aesthetics of fashion photography today, and how designers and photographers—self-conscious postcolonial players in the field of fashion—have chosen to negotiate with the nation’s colonial past.

However, this form of postcolonial negotiation is not as straightforward as it may seem at a cursory glance, and the motives behind this are far from being solely an attempt to reinstate a lost cultural identity and pride through fashion. While being a tool for such reinstatements, the nostalgic depictions of glamour and splendor become a potent tool for marketing.

Sabayaschi’s Re-Orientalist Vision

Unlike other countries, India’s biggest market share in fashion is enjoyed by the bridal wear industry. With over ten million weddings taking place every year in the country, each of them lasting an average of five days and involving both the bride and groom’s immediate and extended family, it is a lavish affair. Each of the five days, comprising various rituals and ceremonies, requires new and different attire. In 2014, the Indian wedding industry was estimated to be at $25.5 billion with a growth rate of 20-25% every year.[12] With bridal wear accounting for roughly ten percent of the average cost of a wedding, it is a booming industry and more and more fashion designers rely on this industry for success and revenue. Couture Indian bridal wear can cost anywhere from eight hundred to several thousand dollars. All the top fashion designers in the country offer prêt lines, but invest the lion’s share of their creative and marketing energy in bridal wear. Apart from being one of the primary revenue generators for Indian fashion designers, the Indian wedding industry is also boosted by other ancillary industries like high-end decorators, event managers, and caterers. With the invention of “destination weddings”—a wedding event which is planned in a lavish heritage site like an erstwhile palace or fort to lend it an extra exotic value—even the Indian hotel industry has become a large part of the Indian wedding scene over the last decade or so. This move from sets to actual locations, while helping promote locations for destination weddings, also facilitates the imitation of colonial era racial type and royal photographs as the settings provide a sense of veracity to the fashion images.

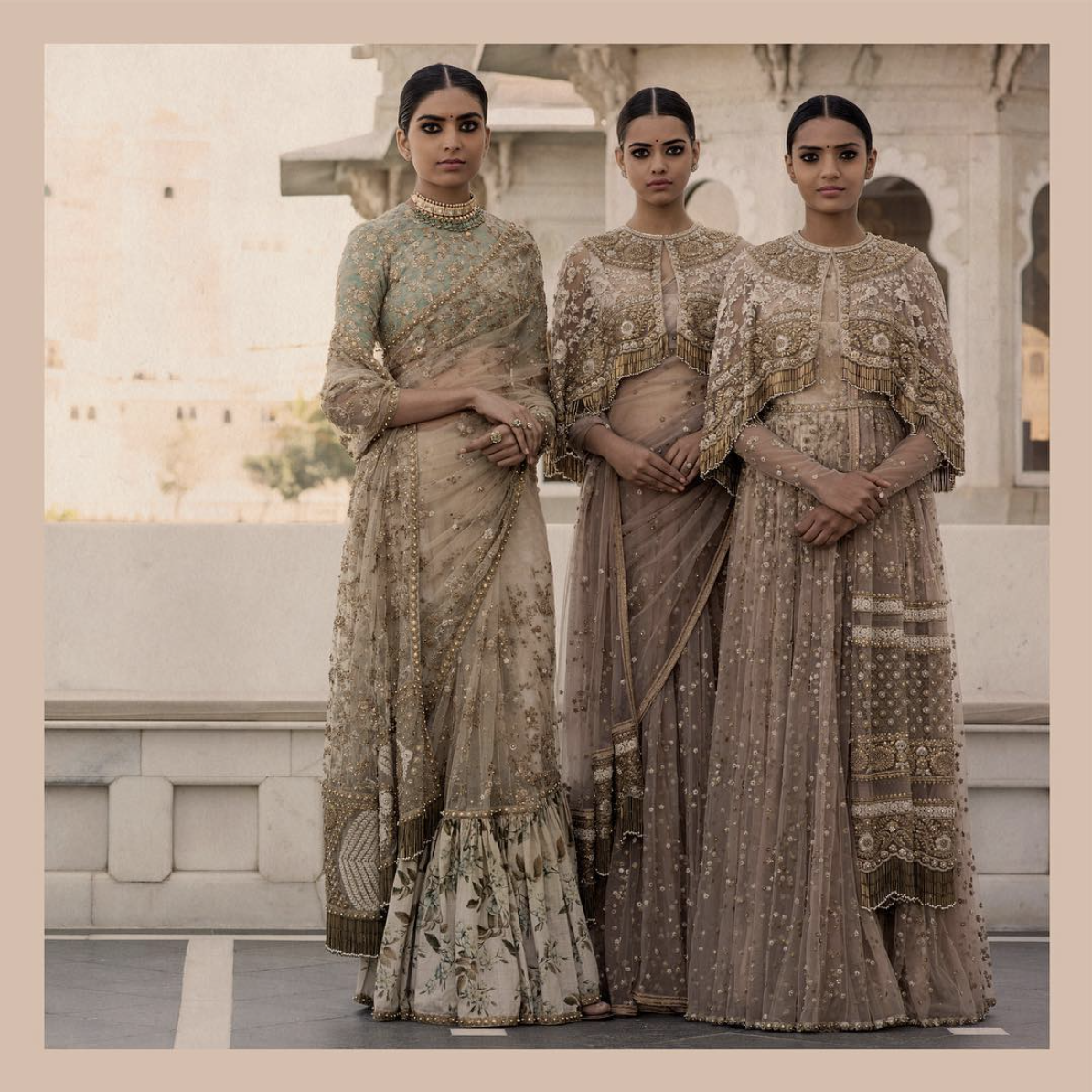

The images for Sabyasachi’s fall/winter 2017 campaign, mostly photographed by Tarun Khiwal, reference colonial era photographs, and as such, place the entire collection within a dialogical framework. Models are seen looking straight at the camera, comfortable with and conscious of the encounter, as sometimes seen in photographs of royal women, but the postures and clustering of figures bear clear resemblances with early colonial racial type photographs. Rarely are models seen in the interiors, but are placed in courtyards or terraces of palaces. Settings, like the Rambagh Palace in Jaipur, are prominently featured in both the images and their accompanying texts, and help situate the figures in a clear historical context.

“Sabyasachi’s fashion discourse is simultaneously a nostalgic lament for dying customs and practices in a rapidly westernizing, global India and a dogged quest to recreate the authentic.”

This trend of romanticizing the past in this particular method has not remained exclusive to Sabyasachi’s brand. As often happens, other bridal wear designers have started to churn out very similar images for their brands, too—even designers who are his close competitors. For example, when designer Tarun Tahiliani launched his spring/summer 2017 collection “Chashme Shahi”, there were murmurs in fashion circles that he was copying Sabyasachi. The images were remarkably similar in aesthetic to Sabyasachi’s collection from the previous year. For Tahiliani’s fall winter 2017-18 collection, models posed in front of gigantic oil portraits, replicas and originals, of royals. Other photographs featured interior shots with both male and female models, the walls adorned with intricate brocade and floral wallpapers, checkered marble floors, mounted wall lamps—an elaborate and distinctive Victorian era décor.

The texts and images combined in Sabyasachi’s campaigns invoke a nostalgic remembrance of a venerable past, [13] at once fondly remembering age-old customs and traditions and being obsessively fascinated with its glory. For a Banarasi saree from his “Heritage Bridal” collection, the accompanying text presents an account of working with traditional weavers of Benaras. In first person, the text reads, “The Benarasi was dying. Decaying under piles of cross pollinated textiles and human greed. It took me 14 years to get it back on track. Slowly and painfully. But I never lost my patience. Because I was not dealing with a textile, I was reviving my identity.” [14]

This is a tone that he often adopts, be it in texts accompanying his fashion images or what he says in interviews. Sabyasachi’s fashion discourse is simultaneously a nostalgic lament for dying customs and practices in a rapidly westernizing, global India and a dogged quest to recreate the authentic.

But this is not without its dangers. Sabyasachi’s tendency to romanticize the past, especially the Victorian and modern era which was also the zenith of Indian colonialism, almost echo an Oriental fascination with India’s cultural history. Although his work does exhibit a postcolonial cultural consciousness, the constant evocation of a partial, romanticized colonial past also runs dangerously close to recapitulating Oriental stereotypes about the Indian elite and what can be considered its high culture.

Lisa Lau calls this process “re-Orientalism” in her essay, “Re-Orientalism: The Perpetration and Development of Orientalism by Orientals.” While Lau’s concerns are mostly limited to the realm of literature, looking at the works of South Asian diasporic women authors, I would like to extend her definition of re-Orientalism to include the present aesthetic and discursive practices of the Indian fashion industry. Lau’s definition quite comfortably fits this context, but we must make room for one principal difference. Whereas in Lau’s thesis “it is predominantly the diasporic women writers who are the creators and keepers of the global… image of South Asian culture,”[15] when it comes to fashion, it is not diasporic designers that have engaged in creating the image and discourse of such re-Orientalist practices. Sabyasachi is from Calcutta. Other prominent designers who engage in similar practices, like Tarun Tahiliani, Anita Dongre, and Raghavendra Rathore are from Delhi, Mumbai, and the royal family of Jodhpur respectively. They did not have to be physically away from the culture they politicize and comment on, and it is not necessarily true that their interpretations of Indian culture are deliberately misleading or untrue (as Lau also categorically asserts).[16] Their positionality is not dependent on a diasporic status, a crucial differentiating factor upon which Lau’s categorization of re-Orientalists rests.

It can be argued that the status and positionality of these designers are more akin to that of a global cultural citizen with roots in Indian culture rather than that of a striated Indian one. All the designers mentioned in this paper are global representatives of Indian fashion culture, and enjoy global prominence, organizing events and shows with equal success even outside India. The ease with which these designers create line-ups for foreign labels and whip up collaborations (for example, Sabyasachi’s collaboration with French footwear designer Christian Louboutin, or his hybrid line for retail company Lane Crawford) makes their movement between Indianness and globalness much more fluid and fraught with cultural hybridity and contradictions. In this respect, their status becomes similar to that of the “Third World Cosmopolitans”: upper-class and upper-middle-class English-educated communities in Third World countries who are very much in tune with the rest of the world, but mainly the First World countries, in terms of culture, education, travel, and economic status—conferred to diasporic South Asian writers by Lau.[17] The wide coverage that they receive in English-language media outlets in the country only strengthens this position.

Bridal wear garments are essentially performance pieces. They allow the participants in the ceremony the chance to inhabit a past moment in the present one. The ritual of marriage presents itself as the symbol of timeless authenticity within whose bounds its participants can perform multiple identities and live within the past, present, and future simultaneously. This concept of timeless authenticity is precisely what fashion images for bridal wear try to capture, with pomp and pageantry recreated from colonial era photographic archives.

“He has explored the photographic history of colonial India and has constructed a vision of the exotic Orient that is a close cultural descendant of colonialist fantasies.”

The marketing for bridal wear shares many characteristic features with advertising and marketing strategies developed in the west during the first half of the twentieth century when producers had to find ways to evoke a nostalgic idea of authenticity in marketing their products to the masses. Elizabeth Outka’s term “commodified authentic,” coined to encapsulate the paradoxical cultural-commercial practices of this era, can also be used in the present context to understand some of the underlying tendencies and machinations of the bridal wear industry.[18] She defines the term as “not… a search for authenticity per se but rather a search for a sustained contradiction that might allow consumers to be at once connected to a range of values roughly aligned with authenticity and yet also to be fully modern.”[19]

Sabyasachi’s persona as a fashion designer is a big part of his work. The self-fashioning of his identity drives the discourse around his work; and like his work, his persona is also crafted out of paradoxes. In a recent interview published in Bengali daily, he was quoted saying that fashion is “unnecessary,” arguing that “we publicize it as something crucial and necessary” when in actuality it “takes your identity away from you.”[20] He has maintained for a long time that wearing a “Sabyasachi” is not imperative in any bridal occasion, and has often suggested financially viable alternatives to his brand. The “Sabyasachi look,” he says, can be achieved with cheaper and more readily available alternatives, like the traditional saree shops that have been hallmark textile houses for a long time. He has also often explicitly or implicitly encouraged the sustenance of a vast bootleg replica market that has grown around his creations.

This maneuver—of suggesting longstanding ethnic apparel stores as an alternative to his clothes and being silently encouraging of the bootleg-Sabyasachi—has ironically helped him preserve the elite status of his own label. Partly through its high price point, but even more so through this sort of exclusionary marketing tactic, Sabyasachi fiercely separates his pieces from the mass market, preserving “the mystique of the originary object.” [21] A Sabyasachi piece forever retains its status as a one-of-a-kind, limited edition object of high fashion.

The paradox of the commodified authentic does not remain limited to the realm of the bridal wear produced or the images thereof, but also extends itself in the environment Sabyasachi creates to exhibit his designs. All his flagship stores bear his signature stamp: an overarching Victorian décor embellished with vintage Indian pieces collected from a plethora of odd and eclectic sources, and framed paintings and photographs. In his Kolkata flagship store opened in 2010, designed around an existing tree in the premises which he refused to cut down, the walls are adorned with almost a thousand of such framed paintings and photographs, and his inspirations become clear if one goes through them carefully. Among the photographs are pictures of Maharani Gayatri Devi (one of the most well-known royals of India, the Rajmata of Jaipur whom he has often mentioned as one of his inspirations), Nanda Devi, and, in framed paintings, the ornate Tanjore Ganesha.

The store is divided into four areas, out of which only one is used for commercial transactions. Sabyasachi in fact was acutely aware of the effect his store would have on his customers, and his de-emphasizing of commerce was by design. The noncommercial ambience of the stores, not only the Kolkata one, but also the ones in Delhi and Mumbai, is something he has emphasized from the beginning and rigorously maintains. In a 2010 interview he gave to The Telegraph, he said, “I want people to feel the ambience rather than buy clothes for the first few days.”[22] This creates an ambience for a lifestyle, “promising consumers not single products but new identities and new ways to live,” [23] rather than just being a venue where material transactions take place. It exudes a sense of transformative possibilities, aesthetic refinement, and an attachment with the purity of our cultural past… transcendental values which money cannot corrupt.

Conclusion

Sabyasachi has found through his work varying possibilities of reconfiguring and reinventing the postcolonial self, but not without certain pitfalls. His fashion “sells what is sacred, makes the authentic inauthentic, and, perhaps most disturbingly, simplifies or even invents the past and erases its painful features.”[24] He has explored the photographic history of colonial India and has constructed a vision of the exotic Orient that is a close cultural descendant of colonialist fantasies: a dreamland of princes, princesses, forts, gowns, lehengas, sarees, and heavy diamond jewelry. Drawing from many traditions and styles, his work does channel a postcolonial consciousness, making his fashion political. His fashion images—aimed at the nouveau-riche elites of a postcolonial, globalized India as well as the upwardly mobile middle-class—become a performance of the past, an embodiment of the lifestyle and glamour of the colonial elites. The glamour, glory, and glitz of the colonized Indian rulers become the barometer against which present-day lifestyles can be constructed.

Notes

[1] Outka, Consuming Traditions, 14.

[2] Jagtej Kaur Grewal, “Representations of Royalty: Photographic Portraiture in Princely Punjab,” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress Vol. 73 (2012): 729.

[3] Andrew Bank, “Anthropology and Portrait Photography: Gustav Fritsch's Natives of South Africa', 1863-1872”, Kronos, No. 27, Visual History (November 2001): 43.

[4] Ray Desmond, “Photography in Victorian India”, Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, Vol. 134, No. 5353 (December 1985): 55.

[5] Judith Mara Gutman, Through Indian Eyes: 19th and Early 20th Century Photography from India, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982) 23.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Christopher Pinney, Camera Indica: The Social Life of Indian Photographers, (London: Reaktion Books, 1997) 72.

[8] Francis G. Hutchins, Through Indian Eyes: Nineteenth- and Early-Twentieth-Century Photography from India. By Judith Mara Gutman. The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 43, No. 1 (Nov., 1983): 184.

[9] Gutman, Through Indian Eyes, 25.

[10] “Biography of Raja Deendayal,” Raja Deendayal: The Prince of Photographers.

[11] Ray Desmond, “Photography in Victorian India”, 59.

[12] ”The Indian Bridal Wear Market Has Enormous Potential For Indian Designers,” Strand of Silk. accessed November 7, 2017.

[13] Elizabeth Outka, Consuming Traditions: Modernity, Modernism, and the Commodified Authentic (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 10.

[14] SabyasachiOfficial. 2017. “Heritage Bridal”. Instagram Photo, November 24, 2017. accessed November 20, 2017.

[15] Quoted in Lau, “Re-Orientalism”, 572.

[16] Lau, “Re-Orientalism”, 574.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Outka, Consuming Traditions, 4.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Moitra Chakraborty, Bornini. “Fashion is Unnecessary”, Samvad Pratidin, July 22, 2017.

[21] Outka, Consuming Traditions, 9.

[22] Agarwal, Shradha “Sabya’s Little House of Wonders Store Mirrors the Man - Designer Opens Flagship Store With Signature Magic and Memories”, The Telegraph, August 19, 2010.

[23] Outka, Consuming Traditions, 8.

[24] Ibid.