Race in Vogue: Finding Myself in a Space of Exclusion

A great many issues of Vogue sit stacked in my apartment—countless more are boxed up at my childhood home. I devoured books as a child, and I found fashion magazines to be equally captivating. I never skimmed through them; rather, I read every issue cover-to-cover and studied each photograph meticulously. The imagery in Vogue editorials was awe-inspiring, and I warmed to the magazine’s sophisticated tone and polished veneer. I quickly became well-versed in the fashion industry’s rhetoric and intricate mechanisms. I knew that somehow, someday, fashion would play a significant role in my life. It wasn’t until much later that I realized I was set on finding my place within a space that, since its very inception, did not have me in mind. As I started working in fashion communications, I realized that I was facing a real conundrum. How was I meant to authentically brand concepts and images that placed no emphasis on me? Still, I was set on making a mark within this space that did not seem to value my ancestry, culture, ethnicity and upbringing.

Within my family, I had learned that style and beauty were woven of multiple strands of difference. Mama Assia, my maternal grandmother, and Hadja Tamaha, my paternal grandmother, both had unwavering style. My two grandmothers emanated strength and wisdom, perhaps due to the fact that both women had lived and seen, and throughout the process, chosen what kind of women they wanted to be. Their wardrobes—utterly different from one another— commanded my wonder and respect. One Ukrainian, the other from Niger. As entirely different as they looked, these two women were, and remain, the epitome of style. The clean lines and sharp cuts in Mama Asia’s superbly crafted clothing mirrored her no-nonsense approach to life, her pristine deportment, her flair for detail. Tamaha’s gorgeous traditional garments and their rich color palette alluded to a respect for history, a enduring grace, and an unequivocally gracious demeanour.

This realization came slowly. It was only after my impressionable years had gone by that I became aware of the damage done by an industry I held in such high esteem. It’s only in retrospect that I came to see to what extent my notion of beauty and sense of belonging as a teenager were informed by this world. After all, the environment in which I was raised mirrored the fashion landscape and the contrived standards it upheld. Where I grew up, the rhetoric of cultural pluralism and physical assimilation was at odds with the lack of diverse representations of beauty. The mode of dress at school and in the streets only compounded the influence of the commercial fashion industry. As a dark-skinned Ukrainian or a Nigerien who grew up speaking Farsi, I stood confined by restrictive societal appellations, continuously affected by the juxtaposing of rights, privileges, exclusions, and obligations brought about by the dualities that helped define me. What was the overall message? Immaculateness and beauty, it seemed, went hand-in-hand with whiteness. Disney movies, children’s toys, and far too many books had conveyed that idea to me already; how could the enchanting world of style betray me with its disregard as well? The images I revered had been transferring values that were deeply foreign to my ethnically pluralistic upbringing.

“The fleeting moments of praise were shrouded in fetishism, and the sense of “otherness” was consistently present. ”

This story of erasure is in no way unique, and that’s the crux of the problem. As model Ebonee Davis has accurately explained, young black women are subliminally taught through fashion imagery and advertizing that straight hair is beautiful.[1] My bouncy curls that were the product of a mixed heritage and symbolized a forward-looking world were seemingly not to be celebrated, at least not by the media and fashion industry. The fleeting moments of praise were shrouded in fetishism, and the sense of “otherness” was consistently present. What a huge contrast with the celebration of diversity I was accustomed to within my family! Ironically, I continued to respect a system that did not respect me back—years of what strangely felt like unrequited love.

The history of Vogue is rooted in a sentiment of aspiration and refinement. Its cover is the symbol and chosen representation of the magazine’s essence, an emblem of what the publication stands for. So what happens when everyone in this idealized world is white? I can remember every single time Vogue featured a black woman on its cover, whether it be the American, French, or British edition. Let’s be clear: this is not a testament to a high caliber memory, but rather to the scarcity of black women appearing on covers. If I was not visible, did it mean that my looks were inadequate, or that my features were not worthy of this exclusive environment? Was I being told to revere and comply with a definition of beauty and elegance that was not representative of me?

All of this being said, credit should be given where credit is due. Bethann Hardison, Naomi Campbell and Iman formed the “Diversity Coalition,” an initiative which has played a serious part in fueling change within this sphere. The work they valiantly spearheaded upheld my belief that change needed to be driven by key figures within the industry. Michael Kors and Prabal Gurung, for instance, made strides in terms of body size diversity, while Teatum Jones decided to open London Fashion Week with disabled models. Most recently, Kenzo’s campaigns have shown fantastic progress, as they fight against exclusion and choose to sample reality—which, by the way, should not be a rarity. A few days ago, Maria Borges was announced as the new face of L'Oréal Paris.

Noted fashion designer Zac Posen posted a photo of himself clutching a black bag impressed with the words “Black models matter” one year ago exactly. His fight for equality, inclusivity and visibility was made manifest when he cast twenty-five black models out of thirty-three for his NYFW Fall/Winter ‘16 collection.[2] This specific collection paid homage to Ugandan Princess Elizabeth of Toro, which lent itself to a more ethnically diverse model roster. However, it’s important to note that for his NYFW Fall/Winter ‘17 collection, Posen stayed true to his mission of diversifying the fashion world’s imagery by featuring the likes of Jourdan Dunn and Aiden Curtiss alongside—and not separate from—white models such as Lindsey Wixson and Carolyn Murphy. This fact is noteworthy because far too often, there is simply no commitment to enduring change and legacy.

Model Jane Hoffman spoke to Ebony about this “color game,” asserting: “First there was the Negro that looked white. She soothed the company’s conscience. They’d say, ‘We used a Negro.’ ‘Yeah. Where?’ Then there was the Negro girl you’d think of as something else. She wasn’t even beautiful—just a weird creature, some kind of space thing. She had to be so bizarre that no one could identify with her…. Now they’ll say you’re not Negro enough! Such ironies are rather a bitter truth for black models who range in skin color from cafe au lait to very black.”[3] This, by the way, was in 1970. Forty-seven years ago. Here’s what’s most damning about Jane Hoffman’s statement: it still rings true in 2017.

“As reflections of current social paradigms and arbiters of style, fashion images are public memory, embedded in time.”

During the most recent Paris Fashion Week, I came across emails from casting agencies essentially regarding black models as expendable commodities. “We do not want to be presented with models of color,” one said. Joan Smalls, the first black model to be signed as the face of Estée Lauder, has often spoken out about racism in the fashion industry. Model Jourdan Dunn is also very vocal about it on her social media platforms. For instance, last year she tweeted that she was cut from the Dior Haute Couture Show because of her chest size, and that this was a “minor” as she “usually loses jobs because of skin color.” The phrasing may have been prosaic, but the painful message couldn’t help but resonate, especially as it voiced the concern of thousands of models. A platform was being used to address the untold stories of black models’ confrontation with the expectation of whiteness. Booking one black model for a show in order to avoid media scrutiny simply does not do the trick; the root of the problem is left untouched. Quotas must be eradicated, which means that disruption is necessary.

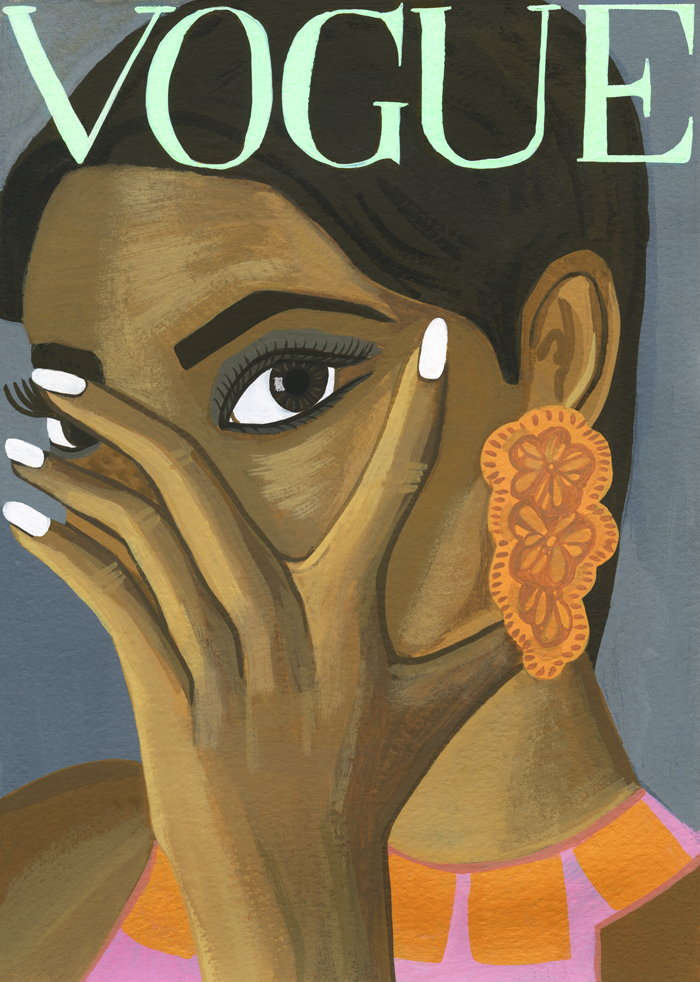

As reflections of current social paradigms and arbiters of style, fashion images are public memory, embedded in time. Vogue covers historically define what society believed to be most important about ourselves and our appearance. Donyale Luna was the first African American model to cover British Vogue’s March 1966 issue. In the photograph, her hand is stylistically placed over her mouth and nose, hiding black features and revealing a partial identity. It would take nearly a decade for Vogue to feature a black model’s entire face on its cover.[4] Until then, black models remained hidden figures, images fragmented and denied of their wholeness. Unfortunately, fashion magazines still provide a fragmented and incomplete reflection of current socio-cultural landscape, while conversely pointing to the very erasure that we, as women of color, feel every day. To this day, black models are unbelievably scarce in this visual record. Some have said that there is a lack of readily available black models, and that is preposterous. They are not absent, or lacking. They are here, and they are being ignored, or used only in ways deemed admissible.

A titan in the international fashion arena, American Vogue’s Anna Wintour has overseen an era of celebrities being featured on covers. She pulled them into the fashion fold, choosing to have her magazine reflect our celebrity-driven culture instead of relying upon traditions that did not resonate in the present. It was once a daring an exciting concept, one that was also an intelligent business move. Pointing to the inextricable link between style and celebrity, Wintour’s decision allowed for more exposure of women of color—four issues in a row of American Vogue featured powerful women of color on its cover this year. Though it’s quite shocking that this was a historical first, it would be dishonest to say that I wasn’t ecstatic when I saw Rihanna grace the cover of Vogue last year in different countries. Or Beyoncé, or Michelle Obama, or Lupita Nyong’o, or Ruth Negga. These covers validated a part of my world that is so rarely placed in the rarefied glow of fashion’s spotlight. Soon after, I began wondering if women of color, more specifically black women, are only “allowed” to be celebrated when they are celebrities. Are just a select few being accepted into this closed off world, or is the industry finally progressing?

“These covers validated a part of my world that is so rarely placed in the rarefied glow of fashion’s spotlight.”

As positive as the development seemed, I simply couldn’t shake the idea that there was a lucrative argument behind this display of diversity. Yes, women of color were being featured, but which ones, and why? Multiculturalism within this context is likely embedded in social, and therefore commercial, relevance. In some ways, using celebrities of color as opposed to models of color on the covers of magazines points to a controlled dispensation of racially diverse imagery. What is the point of black women on covers if historically Western codes of beauty remain the reference within the magazine, and everywhere else in the industry?

Tales of racism in the fashion industry are unfortunately far too familiar and far too common. Nowadays, women of color are both diluted and celebrated. In a desire to impart “edge,” or compelled by external demands for representative diversity, designers and agents now request either extremely dark skinned women or extremely light skinned women with “white features.” How could an entire industry fetishize human beings in such a way and erase every other shade of brown? How could we, as women of color, become collateral damage as trends come and go?

It’s precisely because I value fashion publications and other institutions within the industry that I want to hold them accountable. It’s precisely because I so emphatically believe that images have the ability to teach and inspire, that I care. Pictures are worth a thousand words, they say. In my opinion, the absence of some says much more.

Notes

[1] Hobdy, Dominique. "Meet Sports Illustrated Model Ebonee Davis." Essence.com. October 04, 2016. http://www.essence.com/2016/03/01/sports-illustrateds-ebonee-davis-gets-candid-about-diversity-beyonce-vs-rihanna-and?iid=sr-link3.

[2] Assefa, Haimy. "Fashion designer Zac Posen: 'Black models matter'" CNN. February 19, 2016. http://edition.cnn.com/2016/02/18/fashion/zac-posen-black-models-matter-feat/.

[3] “Have Black Models Really Made it?” Ebony Magazine, May, 1970.

[4] “A History of Racism in Fashion,” Complex Magazine. September 12, 2012. http://uk.complex.com/style/2012/09/a-history-of-racism-in-fashion/.