Smuggled in the Bustle

In 1872, Harper’s Bazar reprinted the poem “Nothing to Wear.” The poem described Miss Flora McFlimsy who, while returning from her shopping trip in Paris, had hoped to get her newly acquired fineries back into the United States by any means necessary:

Her relations at home all marveled no doubt/ Miss Flora had grown so enormously stout/ For an actual belle and a possible bride/ But the miracle ceased when she turned inside out/ And the truth came to light, and the dry goods beside/ Which, in spite of Collector and Custom-house sentry/ Had entered the port without any entry. [1]

This poem was already familiar to many readers in the 1870s since it had been originally published fifteen years earlier in 1857. Not coincidentally, around the same time that this poem reappears, dress smuggling among American women was a subject regularly covered in the media.

In the late nineteenth century, there was steady coverage in The New York Times about the act of dress smuggling. This act, often referred to as "fashionable smuggling,” involved the practice of smuggling European-made gowns and dress goods such as ribbons, lace, and accessories into the U.S. [2] [3] Whether a quick report or an in-depth exposé, the focus of each story is smuggling's relationship with the women involved, and of the women who were reported to have smuggled – a high number of whom were dressmakers and milliners themselves.

It is not surprising that dressmakers and milliners were at the front and center of the smuggling coverage. The American dressmaker understood the American woman’s desire for the latest European fashions and no one was more equipped to provide such fashions – illicitly or not – than the dressmaker. The dressmaker used the elements of her social makeup, that of a working woman with a skilled trade, and the presentation of herself as a “respectable lady” to partake in smuggling goods in order to deceive Custom House inspectors.

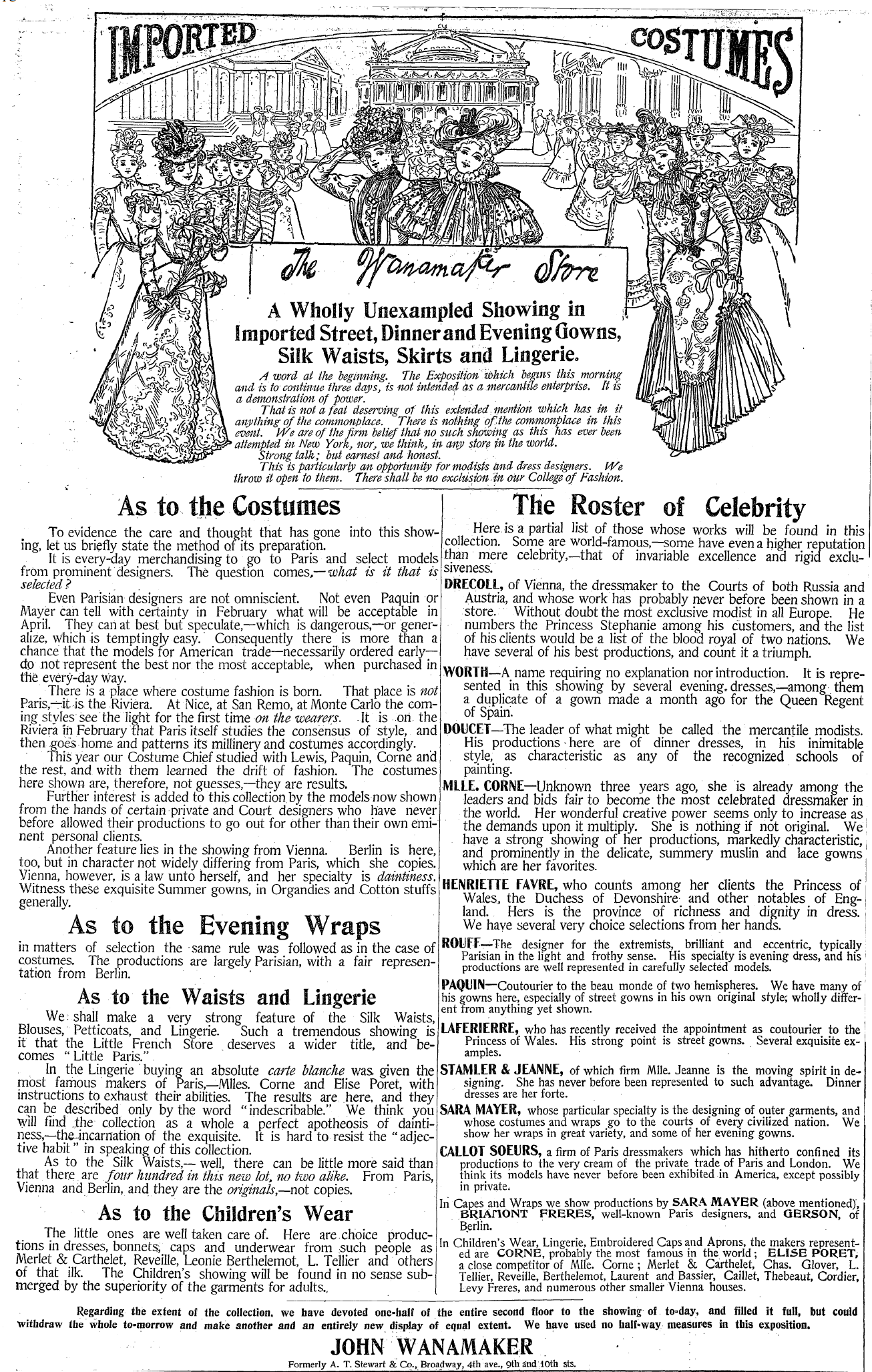

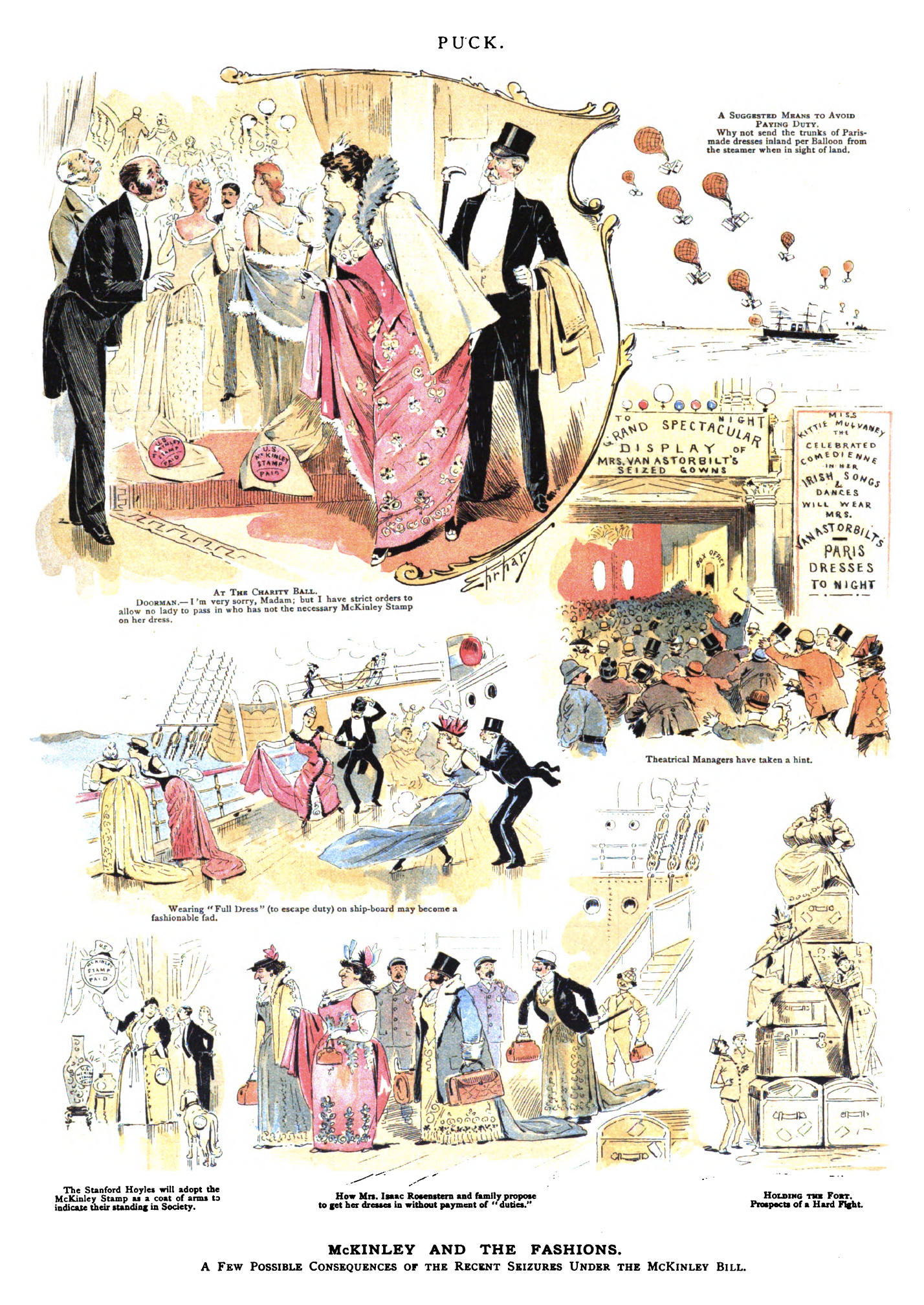

In the mid-to-late nineteenth century, dressmakers, milliners, and their fashionable clients were subject to protectionist policies regarding the importation of European dress goods, which greatly affected the customer's ability to follow notable European fashion. The high cost of tariffs targeted the importation of textiles and other luxury goods. Textiles especially faced high import duties with taxation on silk alone reaching above fifty-percent higher than the cost in the pre-Civil War era. Although there were attempts at tariff reform, the U.S. government continued to impose import duties. In 1890, the McKinley Tariff Act further affected the cost of dress goods such as silk and finer cottons used for lace and embroidery, which primarily came from Germany, England, and France. [4] While the U.S. government did impose restrictions on foreign imports, the American people’s increased appetite for these goods conflicted with the protectionist policies. Historian Andrew Wender Cohen explains this relationship as “Gilded Age Americans' ambivalence toward what we call ‘globalization' and [the] complicate[d] notions of a country lusting for foreign markets and products and a government eager to abet these desires.” [5]

Paris’s reigning influence over western fashion and taste affected the business practices of dressmakers and milliners. They studied fashion plates, copied patterns, and purchased French fabrics and trims with their clients desires in mind. Therefore, in order to follow the trends, dressmakers would travel overseas to European cities to bring back full gowns to be used as samples, as well as French textiles and trims to incorporate into their copies. By providing these Parisian styles, elite dressmakers leveraged their cultural capital and redefined their place in society. Smuggling and averting import laws were therefore necessary risks taken in order to decrease costs. At the same time, however, these illicit practices allowed dressmakers to become arbiters of style the principal lifelines to the main source of fashion: Europe.

American clients’ insistence on French styles and goods sometimes posed complications for those making the dress goods. This agitation was clear when Belle Otis, an American milliner, had to appease a client who believed the flowers in her bonnet were not French. In 1867, Otis wrote in her diary, “What a stretching and straining there is among our ladies after the ‘parisian.’" She then admits the stronghold that Paris has on trends as she understands that she “is not responsible for taste” and that “[she] didn’t create it.” To assuage her client’s fears, Belle Otis kept her customer entertained with a Paris fashion plate while she procured a French label. Miss Otis confessed that she could not remember clearly if it belonged to her client's set of flowers or not, but decided that “it was less trouble to convince her that the flowers were French than to change them.” [6] Indeed, the French label was proof enough and her customer left satisfied. The dressmakers and milliners willingness to blur the lines of ethics helped maintain their clients as well as legitimize their businesses. Deception often became part of their professions while strict import laws reduced the amount of French luxury goods legally brought into the U.S .

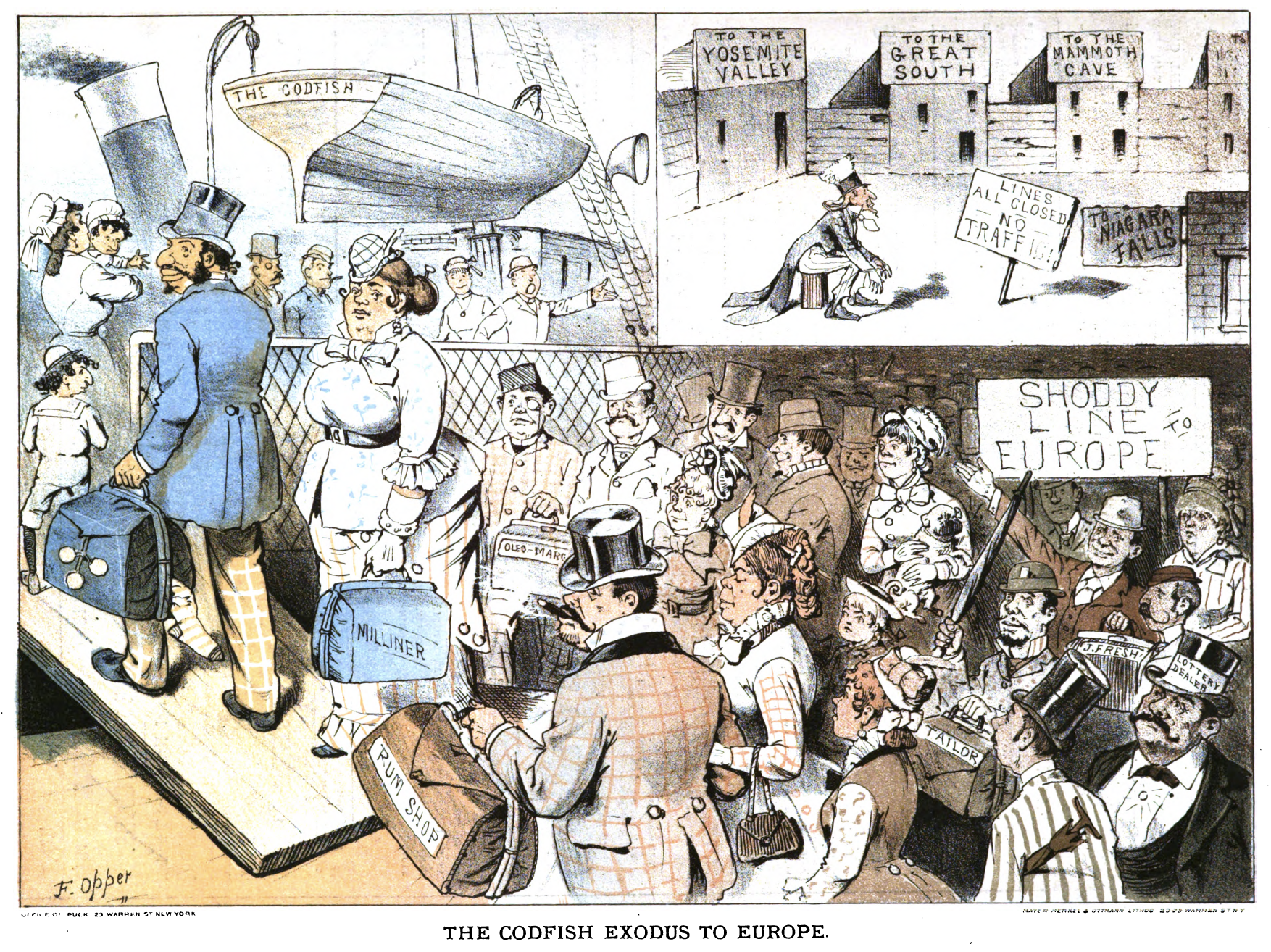

In one political cartoon from the journal Puck titled “Codfish Exodus,” a crowd is ready to board a ship described as a “shoddy line to Europe.” At first glance, the political cartoon seems to be a commentary about the popularity of European travel. Looking closer, the cartoon reveals another important aspect of European travel and its relation to Americans. “Codfish Exodus” most likely refers to the “codfish aristocracy,” which was used to describe persons who made their fortune by trade and often carried a negative connotation. [7] By labeling the illustration “Codfish Exodus,” the political cartoon suggests that middle and working class tradespeople were not only traveling for leisure, but also traveling to benefit their businesses, with their dealings abroad not always being completely honest. Out of all of the occupations and people depicted in this illustration, a middle-aged and overweight woman noticeably stands out in this cartoon wearing a tightly fitted ensemble. She is predominantly featured in a three-quarters profile with her gaze to the viewer. The label on her luggage reveals her occupation: milliner. The milliner’s dominant presence in this political cartoon reinforces the illegitimate nature of the dressmaker and milliner’s purpose of travel, which was acquiring European goods with the intent to smuggle them into the U.S.

The U.S. Custom House was aware of this aspect of travel. As such, the legitimacy of many Americans’ intentions for traveling overseas were a cause for growing concern. Because of this, Treasury Department agents were stationed across Europe to look out for unusual and excessive spending done by Americans abroad. [8] Headquartered in Paris, these officials would often report back to the New York Custom House, where customs inspectors would await the arrival of smugglers.

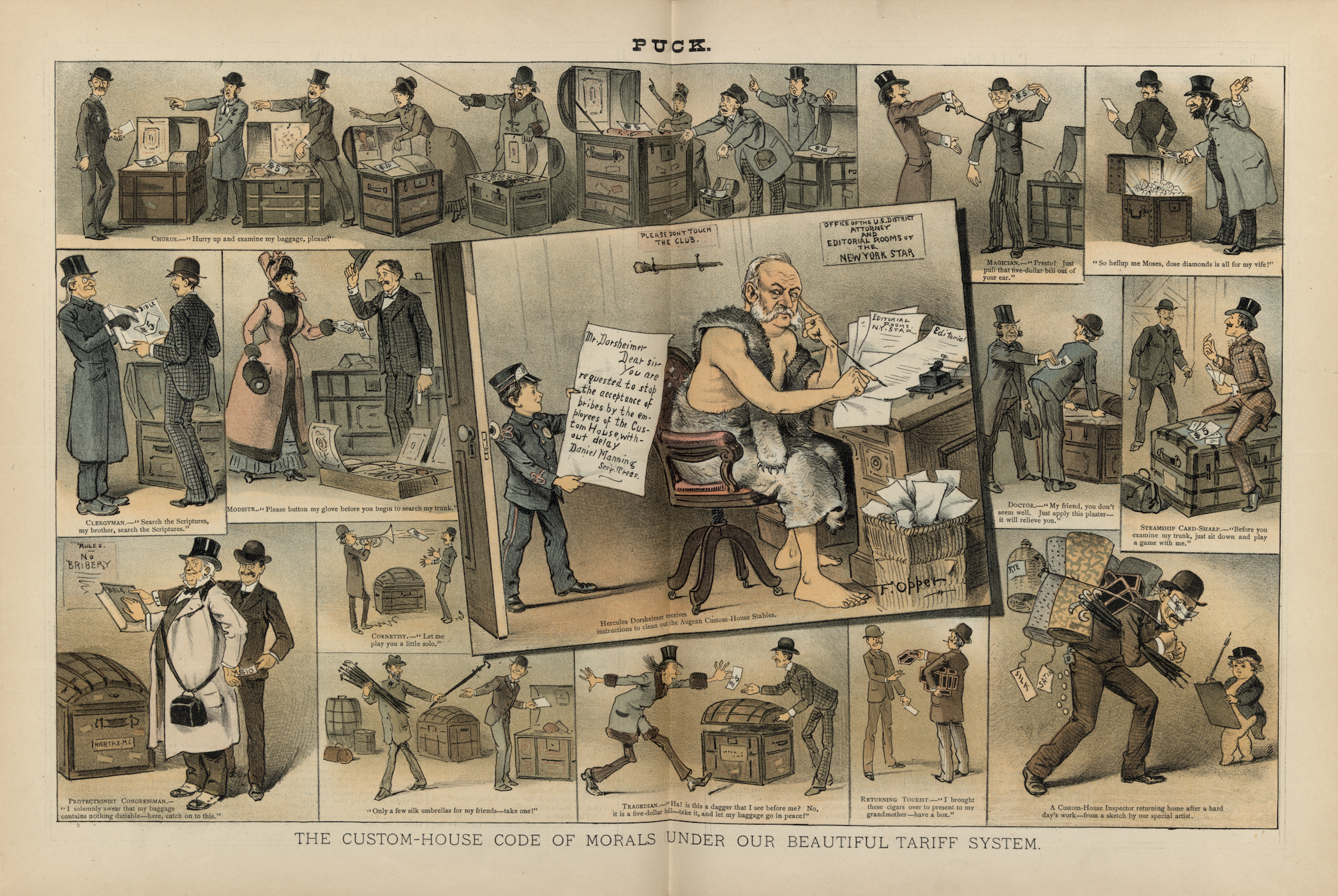

The U.S. Custom House in New York was a federal institution well known to the public due to its regular coverage in newspapers and magazines. The Custom House and its inspectors were known as the “protectors of protectionism.” [9] This was the presumed role of the Custom House, but the institution proved to garner a different reputation. Rather than being known for their patriotic deeds, the blatant and corrupt practices of Custom House employees were highlighted instead. The U.S. Custom House was the second largest federal employer with more than thirteen hundred employed in New York alone by 1877. [10] At that time, a position at the Custom House was a lucrative one due to the practice of the moiety system, which allowed officers and collectors to enjoy a cut in all fines and forfeitures, helping to make some officers very wealthy.

The abuse of this system by some inspectors continued to spread the U.S. Custom House’s image as a corrupt institution. [11] The moiety system ended in 1874, but corruption continued. Bribery between smugglers, inspectors, and crew members was well known with several travelers using the trick of leaving money on top of illicit items in their luggage to encourage the inspector to look the other way.

The U.S. Custom House hoped to shed its negative image with the aid of publications and propaganda pieces. In one Harper's Magazine article from 1884, the magazine describes the Custom House as such: “Three things are perfectly clear to the city of New York: first, the United States of America is the greatest country on earth; second, New York is the greatest city in the country; third, Custom-house is the greatest institution in the city.” [12] In addition to propagating a positive image of the custom house, the article also redirected the focus to the illegal activities of the travelers with special interest placed on the increase of female smugglers, who were primarily dressmakers and milliners. As more women took part in the practice, customs inspectors were faced with a dilemma of interrogating the ladies who arouse suspicion without causing any offense to them. Thus, inspectors picked up on visual clues, particularly dress, to help them in profiling a smuggler.

The smugglers’ main concern was to pass without any suspicion, and deception was the ultimate method used by those hoping the appearance of a respectable and honest person was enough to pass the initial inspection. If the appearance of a lady or gentleman did not suffice, the smuggler then hoped to deceive inspectors by creatively concealing their newly acquired luxury goods. In the a New York Times article titled “Smuggling Craft" from 1879, the writer speaks of smuggling and its relation to current fashions, suggesting that the current trend of the fitted skirt is a direct result of the excessive smuggling occurring at this time. It reads:

To avoid the trouble and vexation of removing her hatches and undergoing a thorough examination at the hands of the revenue searchers led ladies who were not smugglers to abandon crinoline and adopt the fashion of tight dresses that is still in vogue. [13]

Although it is unlikely that smuggling was the primary reason for the popularity of slimmer dress skirts, it does reveal how inspectors took notice of the smuggler’s dress and how inspectors learned to understand fashion trends and the fit of clothing in order to target suspicious women. In fact, fit and silhouette became indicators for inspectors to gauge if a woman was a “respectable lady” or a possible smuggler. Clothing that was worn incorrectly or looked slightly off was likely to catch the inspector’s eye.

Some tried to bypass the tariffs by wearing newly purchased dresses that were not made or intended for them. Dressmakers, who often shopped for their clients, would wear some of these garments, and the improper fit of dresses was a cause for further inspection. For example, dressmaker Delia Gladstone, who was found to have seven gowns in her trunks, tried on all of her garments to prove that they were her personal items and not intended for sale. While the inspector was not convinced by the fit, their opinion was overruled by two female stenographers who thought that the gowns fit true to her size. After paying the duty, Delia Gladstone was allowed to leave. [14]

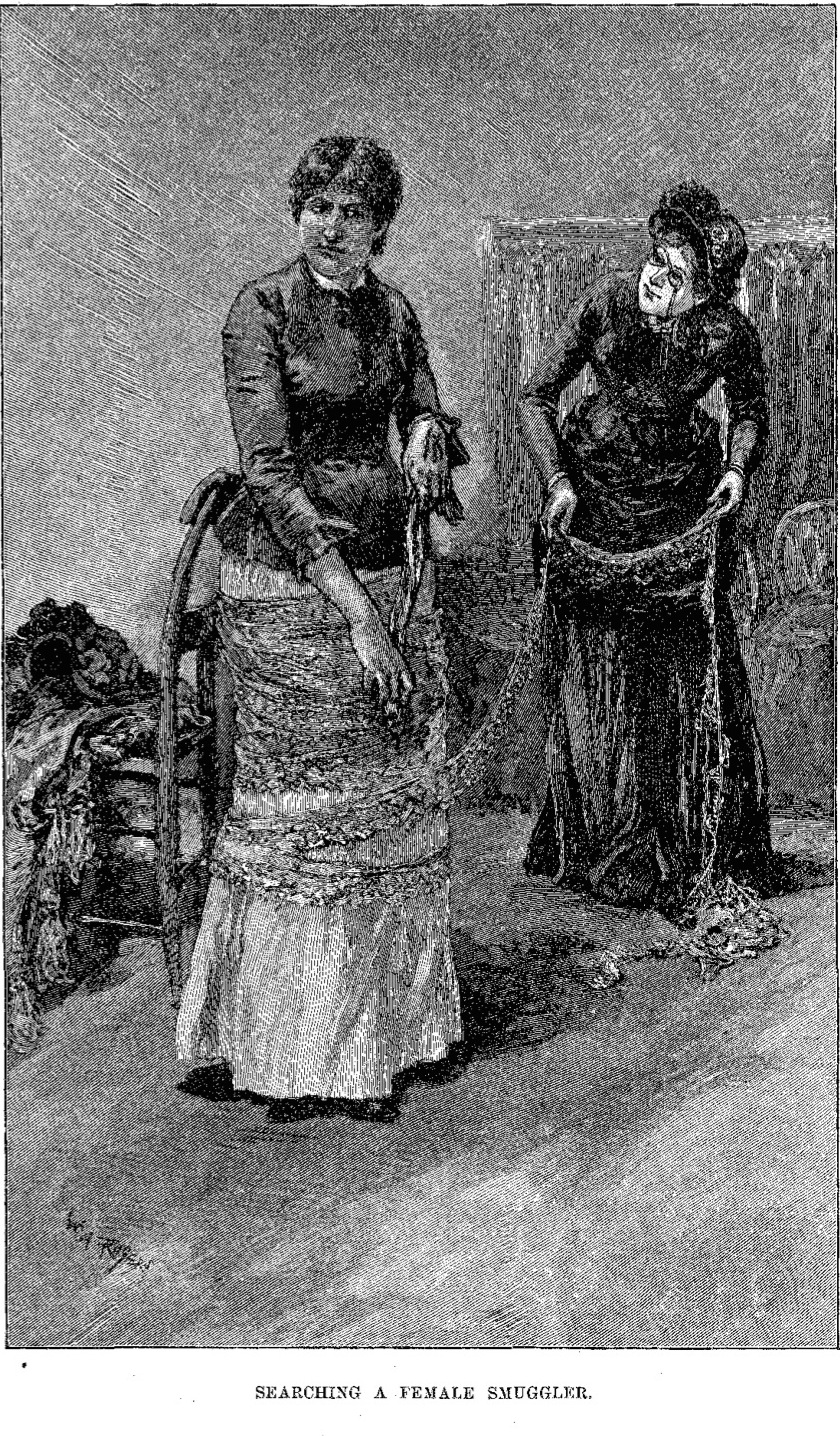

The U.S. Custom House began hiring female inspectors to aid in their seizure duties. The first female inspectors were hired in 1861 as Special Aids to the Revenue Service. By 1867, their title changed to “inspectress.” [15] Inspectresses were brought in when the Treasury Department expected an increase of female tourists. In a letter written to the Treasury Office in July 1881, one collector not-so-subtly suggests that they expected an increase in female travelers returning with goods smuggled and an increase of female inspectors would be needed for their arrival. [16] The implementation of inspectresses was a way for the male customs inspectors to search a passenger without risking their character or integrity when dealing with female passengers. As a New York Times article from 1881 explains, “[an inspector] who is bold enough to chase a pirate all over a ship’s deck if need be, could not very well search a couple of ladies." [17]

Another reason for hiring female inspectors was due to the fact that, since they were women, inspectresses were expected to innately have a greater knowledge of fashion. While fashionable trends like the bustle caused premature grey hairs for the male inspectors, inspectresses detected most seizures through their knowledge of how the fashion should look. [18] Inspectress Mrs. Jennie Ferris (whose name frequently appears in New York Times articles) was even described as: “a magician from the manner in which she brought forth rare fabrics from places where they did not seem to be.” [19] As beneficial as the inspectors’ and inspectresses’ tactics were, most American passengers returning home were able to pass without inspection.

Dressmakers and milliners were especially adept at concealing their illicit goods. By profession, the dressmaker was generally placed in the same class of other working women. However, unlike some of her working peers, the dressmaker directly worked with a luxury product and personally interacted with upper class women as part of her business. Her association with fashion and her interactions with ladies of the upper class led the dressmaker to see herself as her clients’ equal, at least in terms of respectability. It is her fluidity between the two roles—a respectable lady and a working woman with a skilled trade—that helped her elude capture by inspectors and inspectresses.

The dressmaker’s first step to successfully smuggle fashion was to dress the part when traveling. As the dressmaker was the creator of fine clothing, she was well versed in the styles of well-to-do ladies. However, when the dressmaker over-complicated her appearance and attempted to present herself as a particularly “fashionable” lady, she often garnered unwanted attention. The etiquette described in travel guidebooks of the time generally advised that a lady should wear her plain clothing when traveling. In one guidebook from 1897 titled Going Abroad, the author explains:

Every self-respecting man and woman accustomed to the conventionalities of society, wants at all times to be neatly dressed, but it is universally understood that the exigencies of travel do not permit the variety and elegance of the costume customary and practicable at home. [20]

Therefore, a woman that was overdressed in the latest fashions could be putting herself at risk to be mistaken for a smuggling dressmaker. Although it was fit for the ladies of high society, such clothing was suspicious when seen on ships. If the dressmaker could not deceive the inspector by looks and airs alone, she used the other side of her social makeup – her skilled craft and way with fabric – in order to evade duties.

Dressmakers spent years perfecting their skills, which led them to create the dress confections admired by their upper class clientele. It was natural for dressmakers to employ those same skills to the act of concealing smuggled items, and their extensive training with fabric provided them with the ability to hide their Parisian possessions in inventive ways. The dressmakers’ tricks-of-the-trade fascinated and bewildered the customs inspectors. One article in particular from 1878 describes the innate skills of “the swell milliner”:

This lady is as adept in the art of packing, and can force a room full of silk into a Saratoga Trunk. As fold after fold comes forth from its limited receptacle, both wonder and admiration are excited, that so very much can go into very little. [21]

Another tactic often used was concealing the clothes within a petticoat. Often the loose garment became a canvas where other garments were stitched on, and pockets could be sewn to carry extra yardage of fabrics.

While women were at the forefront of the issue of smuggling, it is almost forgotten that they had no political voice or way to affect any change in tariff reform during this time. In one article published by a woman in 1873 titled “Smuggling as a Fine Art,” the author comments on the motivations behind female smugglers and correlates her indifference towards cheating Uncle Sam with the lack of representation that women had in the government, as they were neither allowed the right to vote nor to be part of the lawmaking process. The author questions:

Why should not Lady Midas, the wife of young railway king, use her feminine ingenuity to bringing her nine trunks unrifled and unvalued? The law know her not... It is a dangerous experiment to cultivate and stimulate a woman’s powers in the free soil of the Yankee growth, and then give them no outlet save the feminine by-ways of dress and deception. [22]

The author seems to argue that women had no choice but to devote their full attention to the feminine ways of fashion since they were not useful in a political sense. It’s interesting to note that, along with fashion, the author also marks deception as a feminine characteristic. The author’s belief is that dress and deception are tied together. Although it is doubtful that dressmakers smuggled fashion to serve any political agenda, it is interesting that it was the time when American states first began to give women the right to vote that the first significant changes in tariff reform occurred. [23]

Notes

[1] William Allen Butler, “Nothing to Wear,” Harper’s Bazar, May 27, 1872.

[2] “Fashionable Smuggling: The Tricks that are Resorted to Cheat the Revenue,” New York Times, March 23, 1881.

[3] Ibid.

[4] F. W. Taussig, “The McKinley Tariff Act,” The Economic Journal, June 1891, Vol. 1, No. 2: 338-340.

[5] Andrew Weber Cohen, “Smuggling, Globalization, and America's Outward State, 1870-1909” in Journal of American History, September 2010, VOl. 97, No. 2: 372.

[6] Belle Otis, Diary of a Milliner (Hurd and Houghton, New York, 1867).

[7] Richard H. Thornton, An American Glossary (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1912).

[8] Peter Andreas, Smuggler Nation: How Illicit Trade Made America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 186.

[9] Ibid., 177.

[10] Ibid., 178

[11] Ibid., 178-9.

[12] R. Wheatley, "Custom House," Harper's New Monthly Magazine, June, 1884: 38.

[13] “Smuggling Craft,” New York Times, August 7, 1879.

[14] “Tried on Gowns as a Test,” New York Times, April 2, 1895.

[15] “Woman as a Smuggler, and Woman as a Detective,” Scribner’s Monthly, July 1872, Vol. 7, No. 3.

[16] W.H. Robertson, “Correspondence with Treasury,” August 10, 1881 (National Archives).

[17] “Milliner’s Treasures,” New York Times, August 30, 1881.

[18] “Smuggled in the Bustle,” New York Times, September 20, 1987.

[19] “Milliner’s Treasures.”

[20] Robert Luce, Going Abroad (Boston: Robertland and Linn Luce, 1897).

[21] “Smuggling in the United States: Its Extents, Its Perils, and Its Penalties,” Frank Leslie’s Popular Monthly, July 1878.

[22] “Smuggling as a Fine Art,” Christian Union, February 26, 1873.

[23] Cohen, 395.